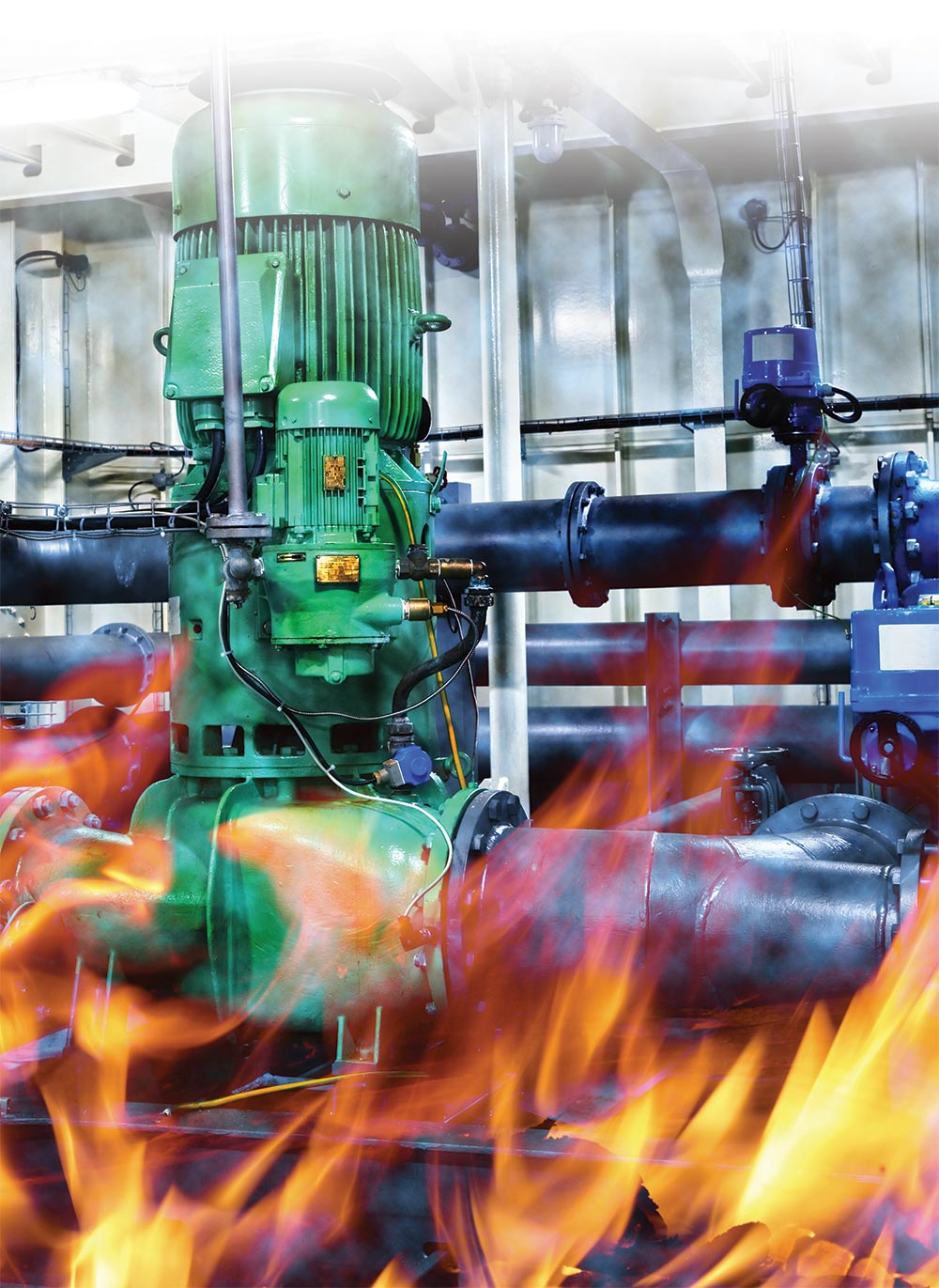

risis management and contingency planning. Those five simple words can cause the most competent business executives to lose more than a few good nights’ sleep. Everyone is busy, and most managers and administrators tend to expend the majority of their focus and energies putting out the operational fires of the day (or week, month, quarter, et cetera). When asked to consider the dire consequences and ramifications of a potential event—especially for those that likely have a small chance of actually occurring—it’s often far too easy to place consideration for such matters on one’s to-do list, perhaps when things quiet down somewhat.

The problem, of course, is that things are never going to quiet down. A whole new set of problems and other “high-priority” issues invariably come to the fore, making it all too easy to push emergency management and contingency planning to the bottom of the pile. If a business or organization is lucky, there will be no real consequence realized from such inaction, as—by definition—the low-frequency event will likely never materialize. However, if such an event were to happen, the high consequence nature of such circumstances could derail an entire operation and perhaps even bankrupt one’s business. Given the high stakes involved, can you really afford to gamble when it comes to such planning?

Most knowledgeable underwriters in any sector are keenly aware of the potential for such operational bottlenecks. When conducting a facility inspection (often as an annual prelude to policy renewal), they will be quick to note any vital or unique pieces of equipment and will make the standard recommendation to stock critical spares on site, should a component failure call for an immediate replacement. Insurers often see failure to stock spares as exceedingly risky and/or downright reckless, and a decision not to stock spares will likely result in significantly higher premiums. The insurer may also create a specific policy exclusion, abdicating itself from any coverage responsibility if a critical component fails with no replacement on hand.

There are several specific actions that I highly recommend, all of which require full explanation and documentation being provided to underwriters:

- For large drive motors, particularly for those with long replacement times, employ and thoroughly document a strong predictive maintenance program, including oil and lubricants analysis that will detect contaminants and other changes indicative of a forthcoming failure in motors, pumps, and gear assemblies.

- For large gears, metal tanks, et cetera, employ and document scanning technology to detect micro-cracks. Such detection could provide several months’ head start in getting a replacement ordered, fabricated, and shipped.

- Especially in light of recent COVID-related events and worldwide supply chain issues, it’s critical to maintain a roster of manufacturers and suppliers of critical components, along with related transport elements, updated on a regular basis. When I took over the risk management and contingency planning functions at a major mining operation, I was shocked to discover how many “planned-for critical suppliers” were no longer in business (or no longer dealing the specific equipment/component needed) when I called to verify the “verbal plans” that had been passed down from previous maintenance supervisors.

- As related above, don’t trust verbal history! If your maintenance superintendent is telling you, “Oh, there’s a spare mill gear of this same size and specifications that’s over at another site, and we have a handshake deal in place to have it shipped over if we ever really need it,” as Ronald Reagan famously said when dealing with Soviet disarmament, “Trust, but verify.”

- If a site’s operations or a process circuit can be reconfigured upon the loss of a critical component, even if it will result in substantially less output, then develop a strong, written contingency plan to do so. The plan should identify the equipment, contractors, and supply chain elements necessary for such a conversion, all determined ahead of time to minimize downtime. Expected changes in output should be thoroughly quantified in the plan so that all parties are fully aware of the true impact of such an event. Such an analysis may be just what’s needed to convince a company’s senior leadership that—in certain cases—the purchase and storage of a critical spare onsite is the most prudent course of action.

The investment associated with stocking a complete inventory of critical spares can range from the somewhat unrealistic to the completely cost prohibitive, particularly for those components with a very low probability of failure. However, before you allow an insurance company’s inspector to frame your decision in terms of “stock-it or pay,” be sure to speak with maintenance supervisors and your own operational risk specialists. Chances are you can take specific, documented actions that may satisfy your underwriter’s concerns, perhaps freeing up some inventory replacement capital for other, more pressing needs.![]()

For expertise from another guest author, choose this article.