Alaska Trends

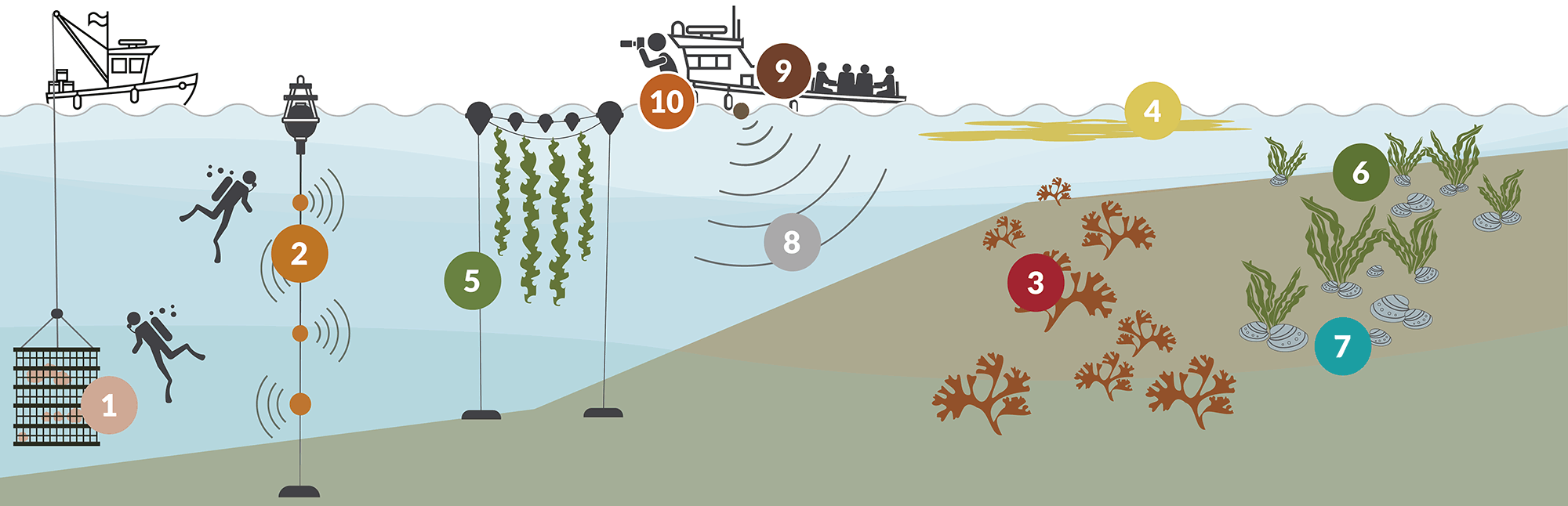

hile farming fish has been illegal in Alaska waters since 1990, that doesn’t mean the state is devoid of mariculture activities. Hatcheries are tolerated because juveniles are released to the wild. Mollusks are fully exempt from the ban, allowing small-scale farmers to raise Pacific oysters and blue mussels. Sugar kelp, known as “kombu” in Japanese cuisine, is also grown commercially. So while some Alaskans already make their living by tending to aquatic organisms, there could be more.

Ocean development agencies and organizations set a goal in 2016 to boost Alaska mariculture into a $100 million industry by 2036. By comparison, terrestrial farming of hay, potatoes, flowers, and other produce is worth between $40 million and $50 million. Inventing a larger industry from nothing might seem impossibly ambitious—except in light of the state’s largest cash crop, cannabis, which rakes in $100 million worth of sales less than a decade after legalization.

Research is ongoing into potential farming of sea cucumber, geoduck clams, blue king crab, and red king crab (the latter two species firmly established as a wild-caught market). The US Department of Commerce and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) are helping to drive the development, partly by laying out a five-year strategic plan.

To track progress, NOAA and its partners released the Aquaculture Accomplishments Report for fiscal year 2023. This edition of Alaska Trends dips into those murky waters and scoops up a bounty of plans and projects.

By the way, one tidbit that takes more explanation than a simple infographic is the role of SMURFs. No, not the tiny blue cartoon characters; SMURFs are standard monitoring units for the recruitment of fish, a collection tool in the form of a mesh cylinder anchored in a marine habitat. By counting juvenile fish that shelter inside the SMURF, researchers compare animal abundance and diversity between farms and natural settings. Smurftastic!

Selective breeding of hatchery oysters

Selective breeding of hatchery oysters Determine aquaculture’s environmental effects

Determine aquaculture’s environmental effects Redesign classroom aquaculture units

Redesign classroom aquaculture units Monitor harmful algal blooms

Monitor harmful algal blooms Assess habitat provisioning of kelp farms

Assess habitat provisioning of kelp farms Assess 100 years of kelp canopy change

Assess 100 years of kelp canopy change Potential for pinto abalone farming

Potential for pinto abalone farming Develop marine spatial analysis data portfolio

Develop marine spatial analysis data portfolio Update ESA Section 7 consultation template

Update ESA Section 7 consultation template Advance aquaculture communication

Advance aquaculture communication