efined petroleum doesn’t just heat our homes and fuel our cars: it ensures Alaska’s economy is a well-oiled machine. But how does a substance formed from the fossilized remains of plants and animals transform into useful, highly valuable products? And of equal importance, how does processed petroleum eventually reach its various end users?

Following its 800-mile journey from the wells of Prudhoe Bay through the winding Trans Alaska Pipeline System, North Slope crude arrives at a tract of land covering 1,000 acres in the northeast corner of Prince William Sound: the Valdez Marine Terminal. From here, the raw product is loaded onto tankers and shipped off to a variety of locations. While it’s true that much of this oil is exported to destinations across the globe, a great deal of product actually remains in the state—contrary to a long and widely held misconception.

Following the refining process, these petroleum products undergo a multimodal transportation mix of truck, rail, marine, and (in some cases) air to reach their eventual end users in Alaska.

The path refined petroleum products take next depends on a variety of factors, with particular regard to the location of the purchaser; there is no single route for heating oil, no single route for gasoline. There is, however, several highly specialized distribution companies working day and night to get these items into the hands and homes of Alaskans.

Founded as Inlet Petroleum Company and now part of the NorthStar Energy family of companies that includes Delta Western, Alaska Petroleum Distributing, and Northern Oilfield Solutions, the revamped Inlet Energy has been providing Alaska with fuel and lubricant transportation services since 1986. The company is well versed in the many ways refined petroleum is being moved around the state.

“Really, there’s a few ways [that fuel comes into the state]—there’s fuel coming in via barge that could be imported from refineries outside of Alaska. Or it could be lifted at the rack via Petro Star or Marathon,” says Lawrence.

Inlet Energy’s sister companies, Northern Oilfield Solutions and Alaska Petroleum Distributing, which operate in Deadhorse and Fairbanks respectively, allow the company to cover a wide swath of the distribution market.

“Inlet Energy distributes fuel along the road system while Delta Western has the marine locations servicing Western and Southeast Alaska,” Lawrence explains.

Inlet Energy’s other expertise lies in lubricants, of which Lawrence says the distribution network differs greatly from gasoline and other fuels.

“There’s no refined lubricants produced in Alaska, it all comes up from the Lower 48 in multiple ways,” he says. “It’s a different model, and I think the transportation part for Alaska is very unique compared to states in the Lower 48 other than Hawaii—the distribution model is very challenging.”

Expanding, Lawrence explains that receiving product from the Lower 48 generally takes seven to ten days, whereas it is typical for distributors in the Lower 48 to receive those same products in twenty-four to forty-eight hours. This leads to Alaska distributors to carry larger inventories and have larger lead times.

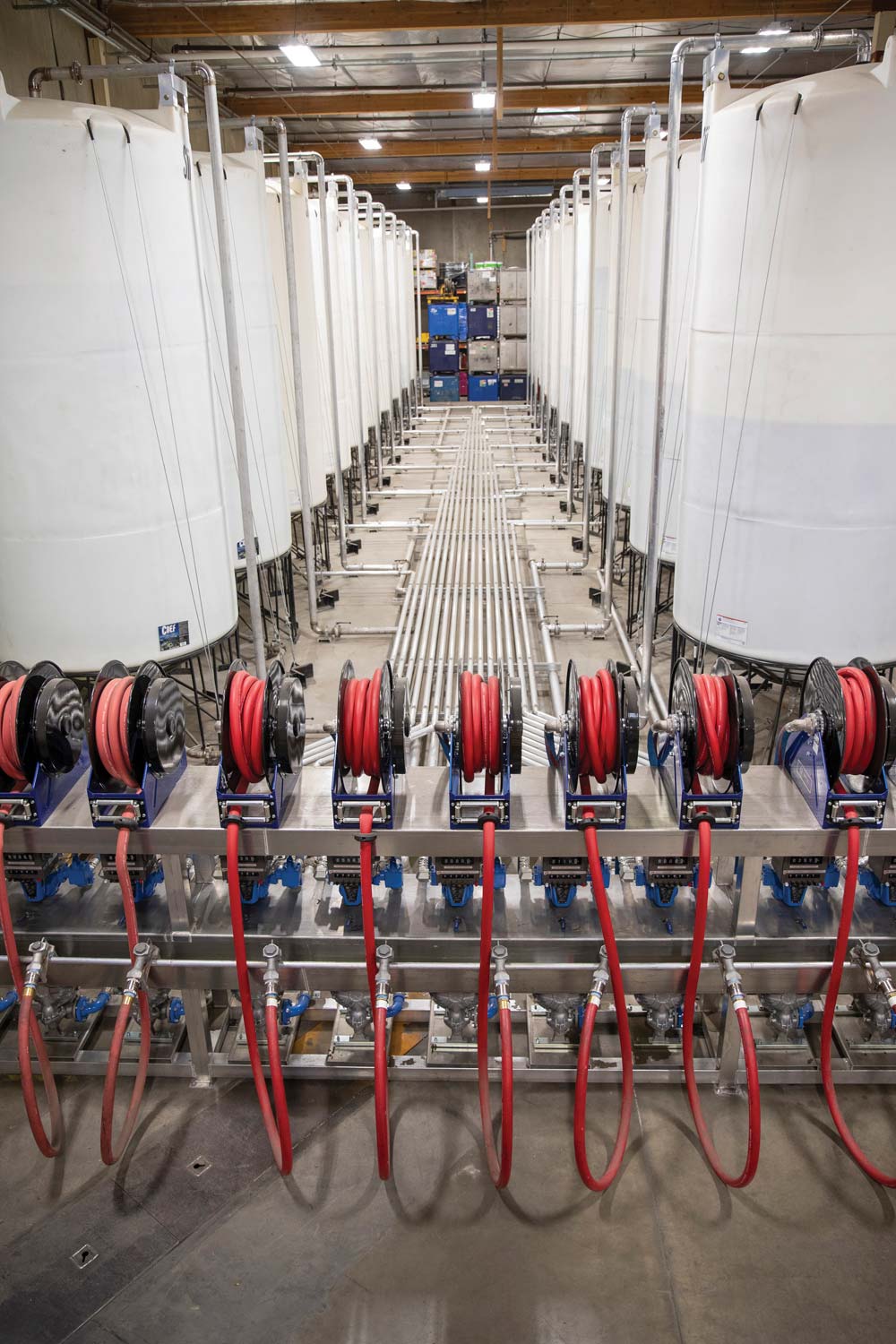

“We typically have a month of supply on hand for our customer base just to make sure they don’t run out of product,” says Josh Parks, Inlet Energy’s director of marketing. “We also have a best-in-class facility where we have twenty tanks that can bring in bulk product,” he says, adding that the product comes in by iso-tanker 6,000 gallons at a time.

Division of Community and Regional Affairs’ Community Photo Library

Division of Community and Regional Affairs’ Community Photo Library

Apart from gasoline, there are a few key products that Alaska individuals and businesses can’t get enough of. Among them—heating oil and jet fuel. Such is the importance of heating fuel that certain executive-branch state agencies have mandatory obligations to keep the product on hand, as per the Shared Services of Alaska. And despite the pandemic decimating gasoline demand worldwide, jet fuel is still one product that the 49th State can’t manufacture enough of.

Crowley began serving Alaska’s fuel needs in 1953. Since then, the company has grown to service more than 280 communities throughout the state. Remote communities across Western Alaska are particularly dependent on heating oil, and a Crowley brochure, “Getting Fuel From There to Here,” breaks down the way in which the company accomplishes this need.

After purchasing fuel from the refineries, Crowley transports fuel to Western Alaska via large, ocean-going barges. Then, the fuel is transferred onto small coastal barges for final delivery to regional terminals or fuel hubs.

Fuel is then placed into a tank farm and stored at regional terminals or fuel hubs. From there, small, shallow draft tugboats and barges transport the fuel to community tanks and tank farms. The brochure points out that the majority of villages do not have docks, so fuel barges must be grounded on the beach to make deliveries. Finally, local tank farms/terminals can sell the product to their customers.

The short answer: a lot.

While the details are often kept proprietary, fuel prices in Alaska are determined by a mix of supply-and demand-based market conditions, in addition to a few other key considerations. The same Crowley document also offers insight into the associated costs of producing heating oil—and fuel costs in general.

One component of price is a company’s overhead cost, which includes indirect costs such as utilities, a company’s payroll, and fees. “Each community has a different fee structure that impacts the price of heating oil,” the graphic states.

Distribution costs vary depending on how far a community is located from a refinery. “Shallow water locations of Western Alaska require transportation with specifically designed shallow-draft vessels,” Crowley’s infographic continues. “Insufficient or non-existent docking and off-loading facilities increase time, safety, and environmental risks, which increase costs as well.”

Inlet Energy

Division of Community and Regional Affairs’ Community Photo Library

Inlet Energy

Division of Community and Regional Affairs’ Community Photo Library

An analysis published in 2010 by UAA’s Institute of Social and Economic Research examined some of the conditions relevant to rural communities that are not accessible by road.

Titled “Components of Alaska Fuel Costs: An Analysis of the Market Factors and Characteristics that Influence Rural Fuel Prices,” the report goes on to divide the communities into two regions: Western Alaska, comprised of North Aleutian villages beginning with Nelson Lagoon all the way up to Kotzebue Sound, and Ice-Free Coastal Alaska, the region spanning Southeast Alaska, Prince William Sound, the Kodiak area, the Alaska Peninsula, and the Aleutian Islands.

The analysis found that fuel in the Western Alaska region was typically more expensive than fuel in the Ice-Free Coastal Alaska region, though fuel costs in Ice-Free Coastal Alaska were still higher than those on the Alaska road system.

The report also notes that while it is possible to fly fuel to most locations in Alaska, flying is only cost effective to communities located within a few hundred miles of refineries in Kenai or Fairbanks. Even then, the quantities would need to be under 5,000 gallons. This is a major reason why marine transport remains the most cost-effective way to deliver fuel to most communities in Western Alaska.

Vipersniper | iStock

Vipersniper | iStock

“You’re starting to see some hydropower and LNG distributed for home heat,” he says. “But I think with distributors like us, we’re looking at additional options, and so maybe that means having more control over supply meaning better storage, more storage for fuel to be brought on, more gallons so you can barge fuel and have a more competitive resource.”

Indeed, according to the US Department of Energy’s Alternative Fuels Data Center, transportation fuel consumption in Alaska peaked in the mid ‘90s, while experiencing a gradual decline ever since.

Distribution companies are well aware of the growing demand for renewable energy production. “You’re starting to see electrification offset some of the fuel footprint—more so in the Lower 48 but eventually it will expand into Alaska.”

Part of NorthStar Energy’s goal with rebranding Inlet Petroleum to Inlet Energy was to align the company with a new mission and vision “of driving a cleaner energy future while guiding customers through the changes of an evolving petroleum industry.” ![]()