ummertime is construction season in Alaska, and while no one can yet predict what the tourist season holds, Alaska’s highways are already heavily used, even before the influx of independent travelers.

There are some places where substantial traffic—and sometimes road conditions—make it more hazardous for drivers to traverse. As a result, Alaska’s Department of Transportation and Public Facilities (DOT&PF) has established Safety Corridors in areas with a higher than average incidence of fatal and serious injury crashes. DOT&PF is also responsible for overseeing the federal Highway Safety Improvement Program (HSIP), which identifies and funds a wide variety of highway safety projects with the goal of saving lives and reducing injuries.

“Back when these four highways were designated as Safety Corridors, they occupied the top four spots as the most serious crash areas in Alaska,” explains Scott Thomas, a traffic and safety engineer for DOT&PF’s Central Region Traffic, Safety, and Utilities Section. “Since the program started, three of them—Seward, Parks, and Sterling—now rank 7, 8, and 9. But we can’t let up; these areas still need policing and media attention, as well as infrastructure improvements.”

This year, work will continue on the Seward Highway on the Bird to Indian Rehabilitation project, which includes paving 5 miles of road and widening sections to create left-turn lanes. The project, which is expected to take at least two seasons to complete, is budgeted at more than $30 million.

“We’re also working on three emergency rock fall projects, cutting back loose rocks in thirteen locations from Indian to Anchorage, and that’s expected to take multiple summers to complete,” says Thomas of the $20 million project. “It’s slow work because we have to close the road when we’re doing it, so it will also impact traffic.”

DOT&PF is continuing work on the $100 million Girdwood to Ingram Creek project on Turnagain Arm, widening the road and creating passing lanes.

On the Parks Highway, the $50 million Pittman Road to Big Lake Road project is expected to start in mid- to late summer. “It will take a couple of years to finish extending the four-lane divided highway, but when it’s completed, we will be able to decommission the safety corridor,” says Thomas. “It will basically be a whole new road.”

This past year was a bad one for travelers on Knik-Goose Bay Road, which recorded three fatal crashes with three fatalities. Safety Corridor improvements in 2021 will include the start of construction on a divided four-lane highway from Wasilla south to Settlers Bay.

“We’ll be doing a few miles at a time,” says Thomas of the $150 million project that is expected to take three to four years to complete. The work will be done in phases.

Plans to make the Sterling Highway a four-lane divided highway are also underway, though that project is awaiting funding, which may take five or more years to arrive. The design process is moving forward in the meantime and will not only include work on the highway itself but improvements to side streets to make it easier for drivers to get to a traffic signal, similar to work done on the Parks Highway and Knik-Goose Bay Road.

“We’re working with the community and borough to find ways to connect blocks to make it safer to access the highway,” says Thomas, adding that this will also provide better emergency access for neighborhoods as well as safer routes for school busses.

In the Northern Region, these include signal upgrades in the Fairbanks area and the construction of an interchange at the intersection of Airport Way, Steese Expressway, Gaffney Road, and the Richardson Highway.

The $25 million signal upgrade project in Fairbanks will include the installation of one signal head per lane and flashing yellow arrows at multiple locations in surrounding areas. The goal of the project, which began in 2018 and is expected to finish in 2022, is to help drivers when weather conditions make it difficult to see the road’s striping.

Installing one signal head per driving lane will make it easier for drivers to line up in the correct location even when snow covers the striping. The new signal heads have retroreflective backplates that increase signal visibility, which has been shown to reduce crashes, and the signals feature flashing yellow arrows to improve compliance and safety for left-turning drivers.

According to Matt Walker, who is a state traffic and safety engineer and the design and construction standards team lead for DOT&PF, one of the unique aspects of this project is that ground penetrating radar was used to discover the locations of underground utilities before digging into the ground. “This saved money by ensuring that the contractor knew where to dig without the danger of hitting hidden utilities,” he explains.

According to DOT&PF reports, this intersection consistently ranks among the top five in the Northern Region for most crashes. Because there is more traffic moving through the intersection than it was designed to accommodate, wait times are also the longest of any intersection in the Fairbanks area, with up to a four-minute wait during peak traffic.

“While the original plan for this project was to build a grade-separated interchange with a cost of approximately $40 million, in the interest of cost accountability and feasibility, the design consultant was able to find an at-grade solution that still provided a significant safety benefit with a much lower price tag,” says Walker.

The project, which is scheduled for 2022 or 2023, will increase capacity, decrease wait times, and minimize vehicle conflicts at the intersection.

In the Southcoast Region, two HSIP projects are in the design stage and are slated to be advertised this fall.

In Sitka, pedestrian safety will be improved by a project at the intersection of Peterson Avenue and Halibut Point Road that will upgrade illumination, provide a pedestrian island, and remove adjacent structures that obstruct drivers’ lines of sight as they turn from Peterson onto Halibut Point Road.

Pedestrian safety will also be improved in Ketchikan at the intersection of Stedman Street and Deermount Street with a project that upgrades illumination and constructs a curb extension on the water side of Stedman Street.

“This project addresses the causes of two recent, fatal pedestrian crashes,” says Walker.

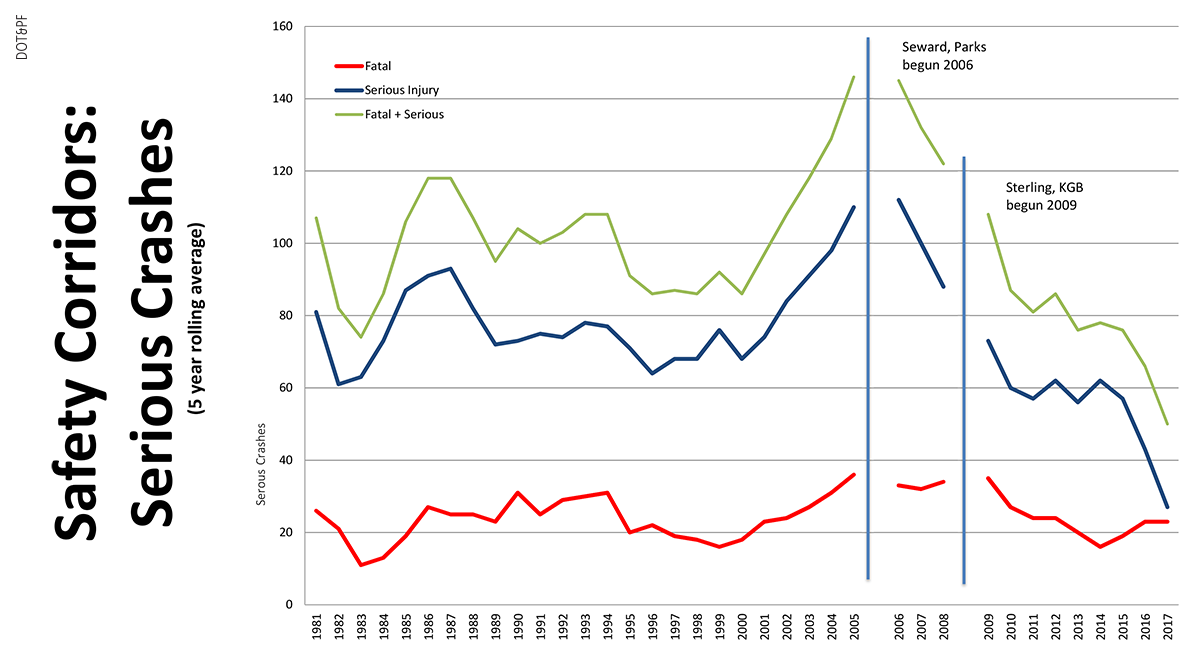

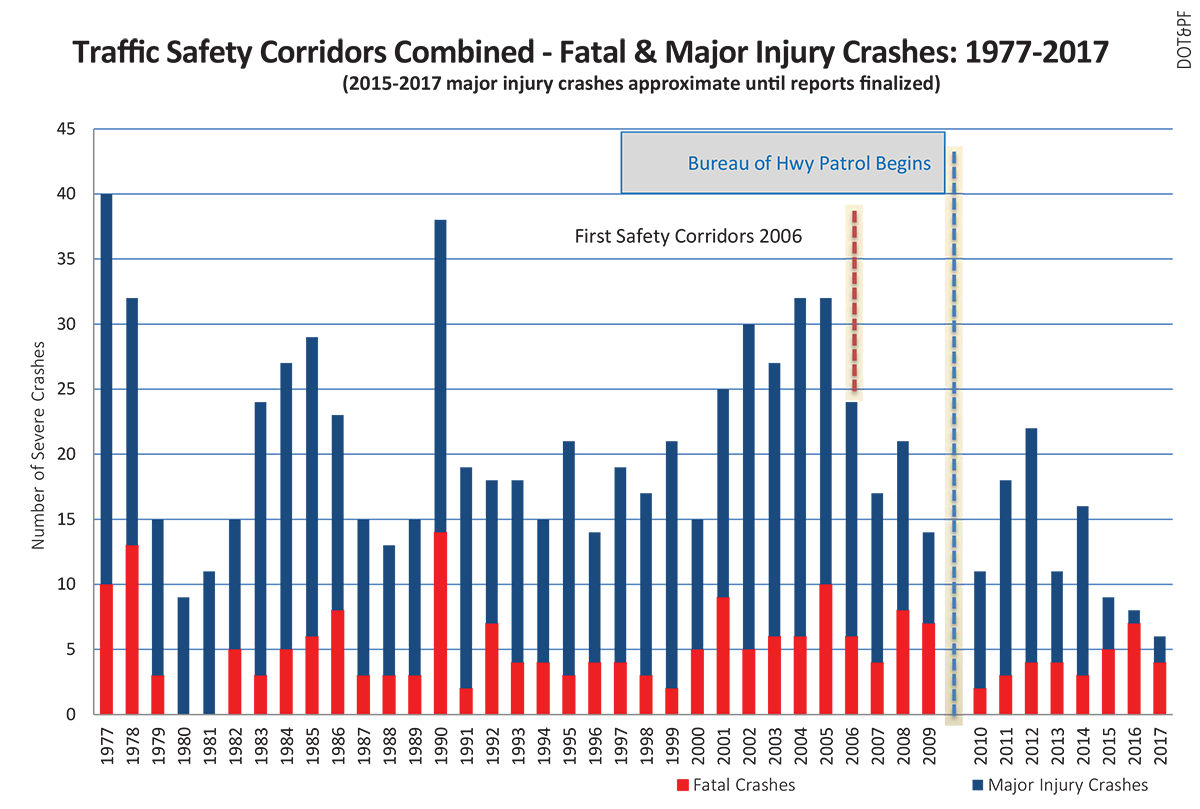

Fatal crashes were up 23 percent between Mileposts 88 and 117 on the Seward Highway, with 2.4 crashes per year, but serious injury crashes were down 55 percent and serious crashes were down 38 percent.

On the Parks Highway, fatal crashes were down 37 percent; serious injury crashes and serious crashes were each down 38 percent.

Fatal crashes were down 18 percent on Knik-Goose Bay Road, with serious injury crashes and serious crashes down 24 and 23 percent respectively. Fatal crashes on the Sterling Highway were down 34 percent, with serious injury crashes down 51 percent and serious crashes down 45 percent.

Overall, fatal and serious injury crashes were down by almost 46 percent since Safety Corridors were designated fifteen years ago, which Thomas credits to the coordination of engineering, enforcement, education, and EMS services.

An addendum to the audit also showed that the highways with Safety Corridors had a 23 percent greater reduction in crashes when tested against similar undesignated corridors. In fact, undesignated candidate highways showed increasing fatalities over the decade while the highways with Safety Corridors did not.

“In contrast, roads without Safety Corridors did not show as great a reduction over time or show a ghost effect,” says Thomas, adding that this carryover effect is credited to drivers changing behavior along the whole road as a result of the corridors.

DOT&PF estimates that as many as 350 serious crashes have been prevented along the full lengths of these four major highways over the past fifteen years.

To combat this issue, traffic offenses committed within designated Safety Corridors come with double fines from law enforcement, and passing within a no-passing zone also adds two additional points against a motorists’ license.

“There’s a small percentage of people that just don’t care, and it doesn’t matter what we build—they have to meet a police officer and get a big fine before it makes a difference,” says Thomas. “Thankfully, the larger percentage do care, leading to increased acceptance that it is okay to drive the speed limit and to not be reckless, which influences the outcomes.”

Fifty percent of the fines from these motorists fund DOT&PF highway safety programs, which can be used to fund additional levels of enforcement in Safety Corridors.

“While things have gotten better since we started, we wouldn’t have seen these results without driver support, police enforcement, and discussion in the media,” says Thomas. “The more people hear about these projects, the more they start reflecting on their actions and thinking about what they can do to make our highways safer.

“We can spend hundreds of millions of dollars, but if the drivers aren’t with us—if they don’t drive the speed limit and leave a little room between vehicles—it won’t change anything,” he adds. “We need people to choose to be cautious and enforcement to help remind those who don’t.”

While work is going on in the Safety Corridors and on other Alaska roads, drivers can find the most updated information, including road conditions and public access restrictions, on the State of Alaska Department of Transportation at 511.alaska.gov. Detailed construction updates can be found at alaskanavigator.org. ![]()