49 Writers

laska is a place of stories. White Fang by Jack London. Fire and Ice by Dana Stabenow. Ordinary Wolves by Seth Kantner. Blonde Indian by Ernestine Hayes. The Raven’s Gift by Don Rearden. The Snow Child by Eowyn Ivey. Into Great Silence by Eva Saulitis. Second Nature by Chaun Ballard. Thousands more titles exist.

“Alaskan authors share a literary genealogy,” says Sandra Kleven, who runs Cirque Press. She invests in book-length, consequential literature written by Alaskans, as do Nate Bauer and Jeremy Pataky, who also acquire books for local publishers—the University of Alaska (UA) Press and Porphyry Press, respectively. Peggy Shumaker edits the Alaska Literary Series, published by UA Press, and is the founding editor of Boreal Books, an imprint of Red Hen Press. To Kleven’s point, these four people along with many other Alaskans form a literary family.

Shumaker, Kleven, and Pataky have contributed significantly to Alaska’s literary community through poetry, essays, short stories, and memoirs. Their other activities have earned them respect as literary citizens. In addition to founding or furthering presses, they’ve taught creative writing courses, established creative writing retreats and workshops, formed and run literary organizations, and championed authors’ works. For instance, Bauer’s press has published Pataky, and Shumaker has recommended authors to Kleven.

For Alaskan writers far away from the world’s publishing hubs, cracking the code on becoming a published author feels daunting.

“A lot of would-be authors are unaware how the process works and operate out of fear,” Shumaker says. “You won’t prejudice an editor by asking a question, so just ask.”

An author may operate out of a variety of false beliefs that prevent them from even submitting a manuscript, such as thinking their view and work must perfectly align with the publisher or that they need to work with one of the “Big Five” publishers—namely Penguin Random House, HarperCollins, Simon & Schuster, Macmillan, and Hachette.

“The world is in love with local,” Pataky says, noting that a similar sentiment applies to more than microbrews and small businesses. “People want to support the labor of love poured into our own communities’ operations.” Alaska presses and organizations, as well as Alaskan readers, are increasingly extending their local support to literary artists, too.

“Alaska has a different idea of what success is,” says Bauer. UA Press serves a scholarly market with academic writing, especially histories and cultural chronicles. “We’ve used creative thinking to help our creative writers,” he says. Although UA Press has operated since 1967, it lost about half of its university funding in 2019. Bauer helped UA Press become an imprint of the University Press of Colorado consortium in 2021. Now UA Press is vibrant and productive again. “In many ways, we’re better positioned than we’ve ever been,” Bauer says.

McCarthy-based Porphyry Press, from its home in the Wrangell Mountains, specializes in the “solitude and community” of circumpolar writers, such as literary history by Tom Kizzia (left) and memoir essays by John Messick (right).

Porphyry Press

McCarthy-based Porphyry Press, from its home in the Wrangell Mountains, specializes in the “solitude and community” of circumpolar writers, such as literary history by Tom Kizzia (left) and memoir essays by John Messick (right).

Porphyry Press

Bauer raises a perspective that most people, even many authors, haven’t considered. For micro, independent, and academic presses, selling thousands of books is not a prerequisite for publication, as is often true for the “Big Five.” Smaller print runs sold to tight-knit customer networks and libraries can demonstrate success. “That’s what presses like ours are set up to do,” he says, “and it works most of the time.”

Circulating knowledge and art plus representing new voices and ideas motivates small publishers, including Cirque Press, Porphyry Press, Red Hen Press, and UA Press. Sales matter to them insofar as they, at least, don’t go into the red. Luckily, few Alaskan literary authors expect to make money, instead writing for pleasure, art, and the connection it brings to others.

“Hardly any author can say one book has sold 5,000 copies,” Pataky notes. “Selling that amount shows tremendous achievement.” However, Porphyry Press’s first title, Cold Mountain Path by Tom Kizzia, has sold more than 6,500 copies, helping springboard Pataky into the book publishing world. For now, he aims to publish one book about every eighteen months. “Most authors get very little support from their publishers unless they’re the rare lucky ones,” he says. “Reining in the number of books in my catalogue protects my capacity to do a great job on prepress and launch promotions for each work I acquire.”

The other publishers agree with Pataky. “Small presses keep works in print,” says Shumaker. She offers an anecdote about her friend who is a well-known fiction writer. The person believed their novel was out of stock and contacted the publisher who acquired it, only to be told it was out of print. “The novel was gone,” Shumaker recounts. “It had a shelf-life about as long as yogurt.”

“Cirque Press sticks with Alaskan artists almost entirely because our state has great writers with amazing manuscripts waiting to get picked up, who are receiving rejection letters,” Kleven says. These authors have often tried many times to get their books published, and their motivation is dwindling or gone.

“When we’ve published their books, they sell out,” Kleven adds, “and their authors do readings in packed venues.” As accolades mount, Cirque Press adjusts its priorities to continue promoting its books, unlike large presses.

To make these adjustments, small presses and their writers have usually laid the groundwork when they began exploring publication. “The relationship between a publisher and author is a pretty intimate thing and should be handled that way, though it isn’t always,” Pataky says. “Beyond editing and honing the manuscript comes discussions about production, promotion, and royalties.”

As an example, he recalls Porphyry’s first title. Pataky says, “Tom and I determined we were compatible through wide-ranging conversations over a long period of time before signing a contract.”

Shumaker gives both scenarios. “For Boreal Books, if I say yes, I send it on to Red Hen Press,” she says. “If they also say yes, then it goes into production.”

Porphyry Press

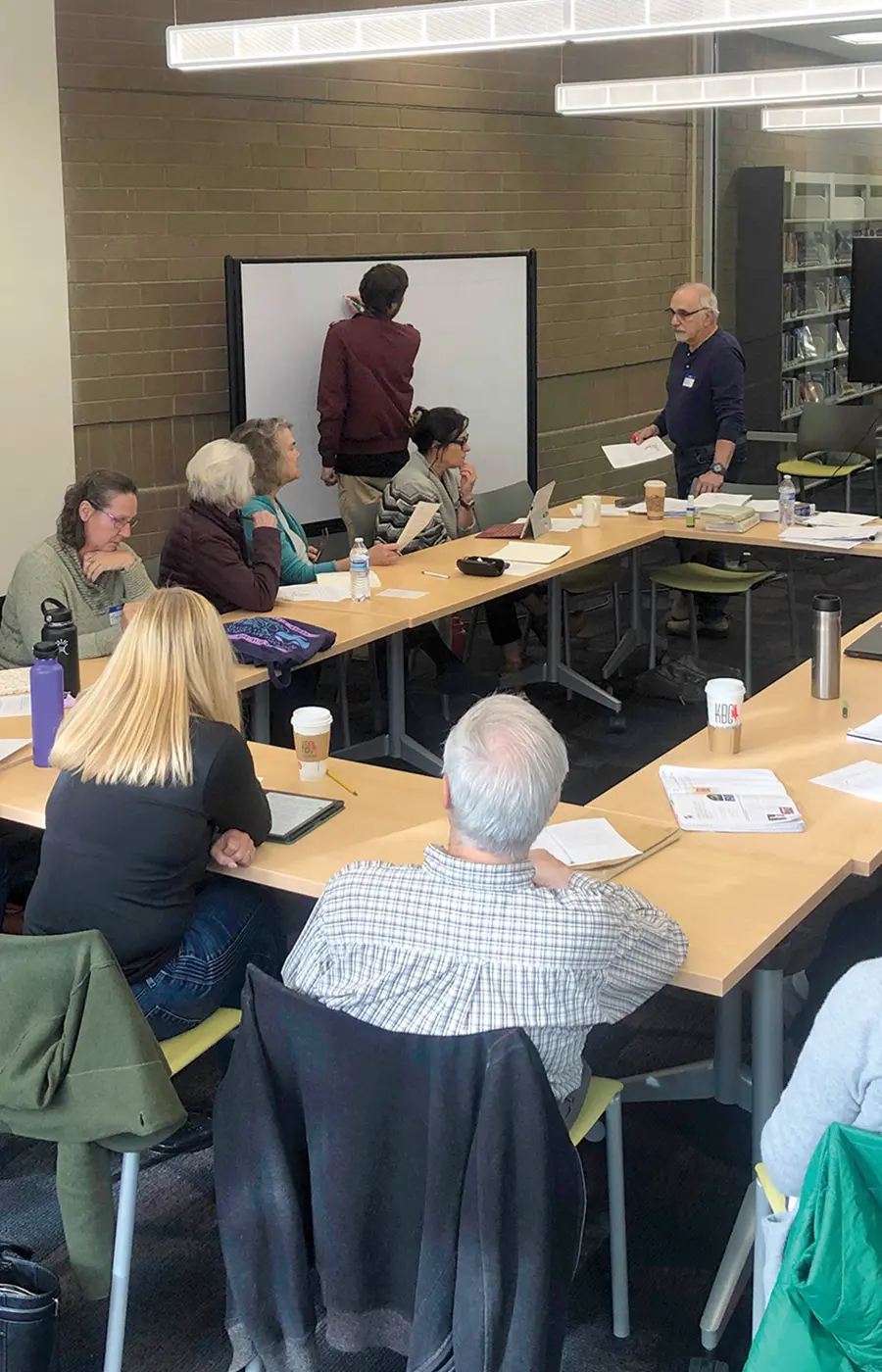

Writing can be solitary, so nonprofits like 49 Writers bind authors with activities such as the Friends, Family, and Food class led by Rich Chiappone and Justin Herrman at Loussac Library.

49 Writers

“If the two required outsider reviewers provide positive reports, then it goes to press staff with an acquisition memo that summarizes its audience and other relevant factors,” Shumaker explains. “They package it for the board, which must confirm it can be evaluated for final review and approval.”

No Alaska press pays advances like the “Big Five,” and less than 1 percent of authors even qualify for an advance. However, local presses add value to authors through offering unique incentives. Their authors may participate in cover designs, receive higher quality prints, benefit from promotions and award nominations, secure better royalties, or request subsequent editions.

Authors who sign with small presses tend to receive better compensation too—at least, a dollar per copy sold and often more. Larger presses usually pay them less than $1 per copy after they’ve covered their own expenses, including printers, warehouses, distributors, and wholesalers.

“If an author gets, say, $2 per book and sells 500 copies, that’s practically nada,” says Pataky. “The money they make comes from offshoots and side opportunities,” such as invitations to teach or lecture, requests to be a keynote speaker, or grants, awards, and residencies. After a brief pause, he adds, “Which means they often do better than the presses.”

Pataky laughs. “We’re happy enough to break even.”

“I can tell you what Cirque makes on our journals,” Kleven says. “They have a cover price of $30. For issues sold via Amazon, Cirque earns around $0.83.” That amount, astoundingly, spikes to $14 if a hardcopy is purchased in-person.

“Honestly, the revenue difference doesn’t impact us. We’ve planned for it,” says Kleven. “So long as the book and its author is doing well, we’re delighted.”

“Success looks different for different authors and different presses,” Bauer confirms. “The amount we sell matters, of course—and we have books that sell 5,000 to 10,000 copies—but that’s not our primary objective.” Like other Alaska presses, UA Press strives to further knowledge and insights packed in literary works. “Finding the right readership is what counts.”

“When I was named Alaska State Writer Laureate, my time came,” she says. “I chose to establish the Alaska Literary Series for my project.” Her determination has made Alaska more welcoming and accommodating for people like Bauer, Pataky, Kleven, and many other creative writers, like Alison Miller, executive director of 49 Writers.

“Sometimes creative writers feel like we’re alone here, struggling with a draft and trying not to chuck it out the window,” Miller says. “We must choose to make the process a social activity, even though writing’s inherently isolating.” Alaskan literary-press trailblazers, like Shumaker and the other publishers, have paved the way for people like Miller to map a creative writing future.

“There’s always more room for connection, whether that’s resources or people,” Miller continues, stressing the role that defines 49 Writers, which is a product of Alaska literary forebears like Pataky.

When a creative writer hangs around long enough, they’ll meet an author who may become a mentor and direct them to literary communities. “That’s what Alaska is,” says Miller, “a land of perseverance, opportunities, and stories.”