Cattle

Patricia Morales | Alaska Business

f only our Neolithic ancestors could see us now. They’d hardly believe that farming and animal husbandry, which transformed society roughly 12,000 years ago, could be done from miles away without stepping in a pile of manure.

Alaska farmers and ranchers have not been practicing animal husbandry for as long as those in the Fertile Crescent, but Alaskans are early adopters of new technology. With factors stacked mostly against raising crops and cattle here, Alaskans tend to jump on board if there’s an advantage to be had.

From camera-monitored calving and wireless fences to robotic milking machines, Alaskan farmers and ranchers are using modern tools to make the most of what Alaska has to offer.

Hungate Farms, which Saunders operates with her husband, is a side project and labor of love that they’ve carved out of roughly 280 acres north of Wasilla, in the foothills of the Talkeetna Mountains. It’s a year-round operation, selling farm-to-table beef and pork. The beef is Black and Red Angus cattle, with a little Hereford blood in the herd. The pigs are a mix of Berkshire, Yorkshire, and Hampshire breeds. All the livestock are born, raised, finished, and butchered at the farm.

There are two things a modern farming operation, especially one set up as a side venture, needs to have: reliable power and reliable internet. While the farm is connected to local power, Saunders says they’ve learned they need backup. A January 2022 windstorm took out power for several days, which meant the stock water tanks weren’t running, among other issues. It’s an event Saunders says they don’t want to repeat.

“Our water is on demand; when we’re out of water, there is no backup,” Saunders says. “We decided we wanted to go with a Tesla Power Wall, a large lithium-ion battery. It’s Phase 1 of our backup plan. We have four Tesla Power Walls, and then our goal is to have solar, so the solar will charge the batteries.”

Saunders says she hopes that, once the solar panels are in place, the farm can primarily run off solar power in the summer, which will help cut down electrical costs. The solar portion is still up in the air; Saunders has applied for an agriculture-focused rural energy 50/50 matching grant and hopes to hear if they’ve received it later this year.

Renewables are a focus for Hungate Farms, Saunders says. She and her husband have electric vehicles and brought one of the first electric tractors to Alaska. Solectrac, a California-based company, has been making tractors for several years but really gained a foothold in 2021 when Soletrac was purchased by Ideanomics, a company whose mission is to accelerate the commercial adoption of electric vehicles. Hungate Farms uses an e25G tractor, the smaller of the two versions Solectrac makes. In the year and a half they’ve had it, Saunders says it has suited their needs well.

“We can use it indoors; there are no exhaust emissions, and it’s indoor-user friendly,” she says. They keep it in the heated barn and, although battery use depends on temperatures outside, the tractor can often go up to a month without recharging. They use it for moving around grain, fencing supplies, manure, bales of hay, stock trailers, mineral tubs, et cetera. It charges with a simple 110-volt outlet, which makes it easy to incorporate into the farm.

“Starlink was another big move forward for us, to be able to have the cameras. I can see if a pig is birthing and go home,” Saunders says.

“This spring, we had cameras up in our calving barn and, during the day in our office, I noticed one of our heifers was not acting like she usually does. On the camera, I saw that she had prolapsed,” she says. “If I hadn’t had the cameras and Starlink, I wouldn’t have known that, and she may have died.”

Moose-proof Fencing

While remote monitoring and electrical stability have proven vital to keeping the farm on track when working several miles away, Saunders began using a new tool this summer that is even more exciting: wireless fencing. The virtual fence requires internet connectivity through Starlink. Customers without property-wide internet can install a base station that beams coverage to the collars, Saunders notes.

Hungate Farms is the only user of the eShepherd system in Alaska, and definitely the furthest-north user, Saunders says. Bill Gallagher Senior, the founder of Gallagher Animal Management, is also the inventor of the modern pulsed electric fence. Gallagher was founded in New Zealand, although it now has offices in Australia, Europe, Chile, North America, and South Africa.

A component of the Tesla Power Wall is mounted in the Hungate Farms barn.

Patricia Morales | Alaska Business

“And naturally, the cattle will want to go back to the herd,” she notes. “Once they re-enter the virtual fence, it resets the collar.”

Saunders says she and her husband have gone to considerable effort and expense to erect perimeter fencing, both barbed wire and electric. The virtual fencing is mainly for the inner perimeter, allowing cattle to graze on a 40-acre block and then gradually move to another.

At left, cows graze in the hilly, wooded acreage of Hungate Farms. At right, Saunders points out features of the eShepherd collars they began using this summer.

Patricia Morales | Alaska Business

Patricia Morales | Alaska Business

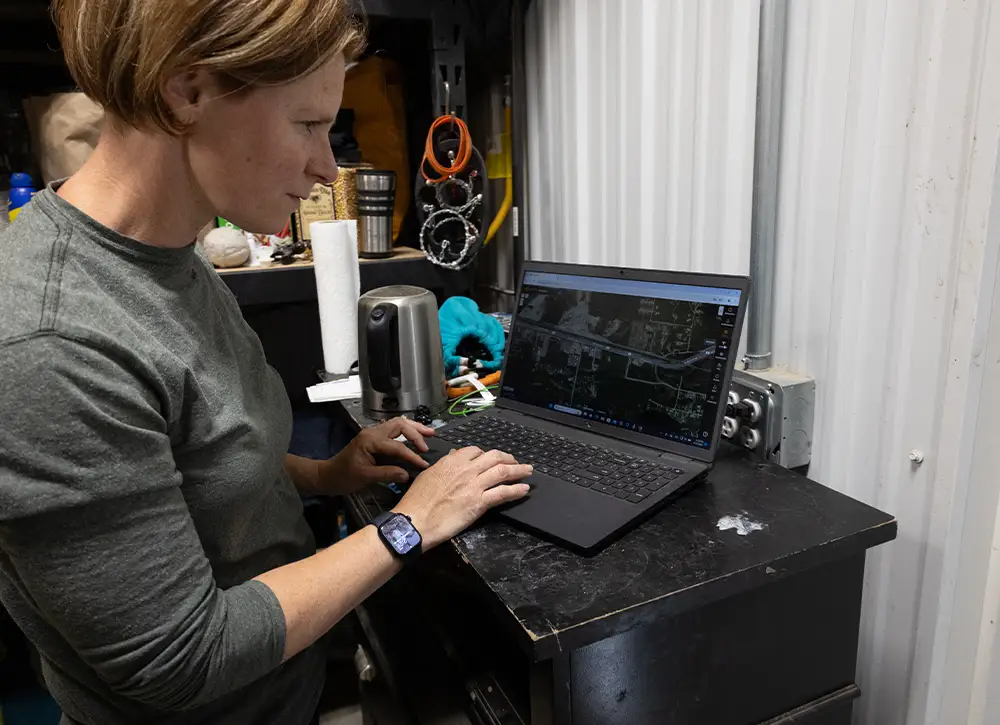

At left, Julia Saunders demonstrates how the eShepherd program works on her laptop. At right, a curious yearling greets farm visitors.

Patricia Morales | Alaska Business

Patricia Morales | Alaska Business

“It was super disheartening to spend the money and invest the time into our fencing, and then the moose would tear it down every day,” she says. “It’s a bigger upfront cost, but it’s worth it in the long run. It’s really nice to be able to pull up the app and see if my cows are out.”

Saunders enjoys working in the construction industry, but she sees the farm as her passion. In construction, keeping abreast of technology and moving with the times is essential. It’s no different for farming, she says, but the focus is a little different.

“I’m passionate about food; I’m passionate about farming. Construction is a good industry for us here, but I love having the farm, having to get out of bed at 5 a.m. and check on the animals,” she says.

Plagerman says his family of four couldn’t have gotten into the dairy business if they had to rely on traditional milking practices—even with automatic milkers. It’s too labor intensive, he says, and there aren’t enough agricultural laborers in Delta Junction. Instead, from the start, his dairy has used a robotic milking machine.

Replacing a milking parlor, the Astronaut A4 is a chute that cows walk into and out of on their own. When they walk in, a collar recognizes the cow and distributes a little feed into a trough. A robotic arm goes under the cow, locates and attaches to its teats, and the milking process begins. Because each cow’s visit to the milking robot is tracked, the food can be modified to correspond with milk output, and things like the temperature and fat content of each cow’s milk can be intricately tracked and monitored.

Plagerman says the cows seem to prefer the freedom; they come and go at will, without having to be herded, which can be stressful. Some cows visit the milking machine twice a day while others might go more frequently, but Plagerman says his herd of about sixty cows averages about three milkings a day. The only limit is that the machine will not respond if a cow has been through just a couple minutes before.

“The system will alert us if the cow isn’t feeling well. We have zero health issues because we catch stuff early,” he says. He’s generally able to treat the issue with minor medications (think an aspirin or antacid instead of prescription antibiotics, for example), and the illness is quelled before it becomes something significant.

The Astronaut A4 is made by Dutch company Lely, an industry leader in dairy robots. Plagerman says, “Efficiency is the main thing of this. We’re a family farm and trying to do all of that with a family, it would be impossible—and with the lack of veterinary service in the state, especially where we are.”

Plagerman also uses a barn floor cleaner made by Lely. Instead of mucking stalls, this Roomba-like device pushes piles of manure into a hole in the barn floor that leads to a holding tank under the barn. The underground storage tank can be cleaned out, and the manure becomes fertilizer, so nothing is wasted—including time spent mucking the barn.

Plagerman added a second robot milker last fall, in anticipation of growing the herd from sixty to eighty cows. With more and more stores carrying Alaska Range Dairy milk and yogurt, the herd must expand to keep up. And high-tech tools make that possible, even in the hardscrabble farmlands of Alaska.