Calista Corporation

laska Native people have faced social and cultural harm that includes epidemics, dislocations, language loss, boarding schools, and more. For decades, communities in every region of Alaska have held culture camps to preserve and restore their cultural heritage and language. The need for these opportunities has grown greater as Elders, who are community experts in language and customary practices, have passed away.

Language is a core foundation for Indigenous cultural identity and heritage, so the loss of Indigenous Elders has been extremely troubling, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic. The damage to Indigenous communities and language revitalization efforts has been devastating. In Kodiak, for example, from 2020 to early 2022, half of the first-language speakers of Kodiak Alutiiq passed away, leaving no speakers of the northern Kodiak dialect and approximately seventeen speakers of the southern dialect.

Additionally, the limited ability to meet face to face has affected language and cultural activities, especially for Elders who are less able to take part in Internet-based communication. Fortunately, this has become less of a problem thanks to COVID-19 vaccination efforts.

With all of these factors, it is a crucial time to preserve and revitalize languages that are endangered or in dormancy.

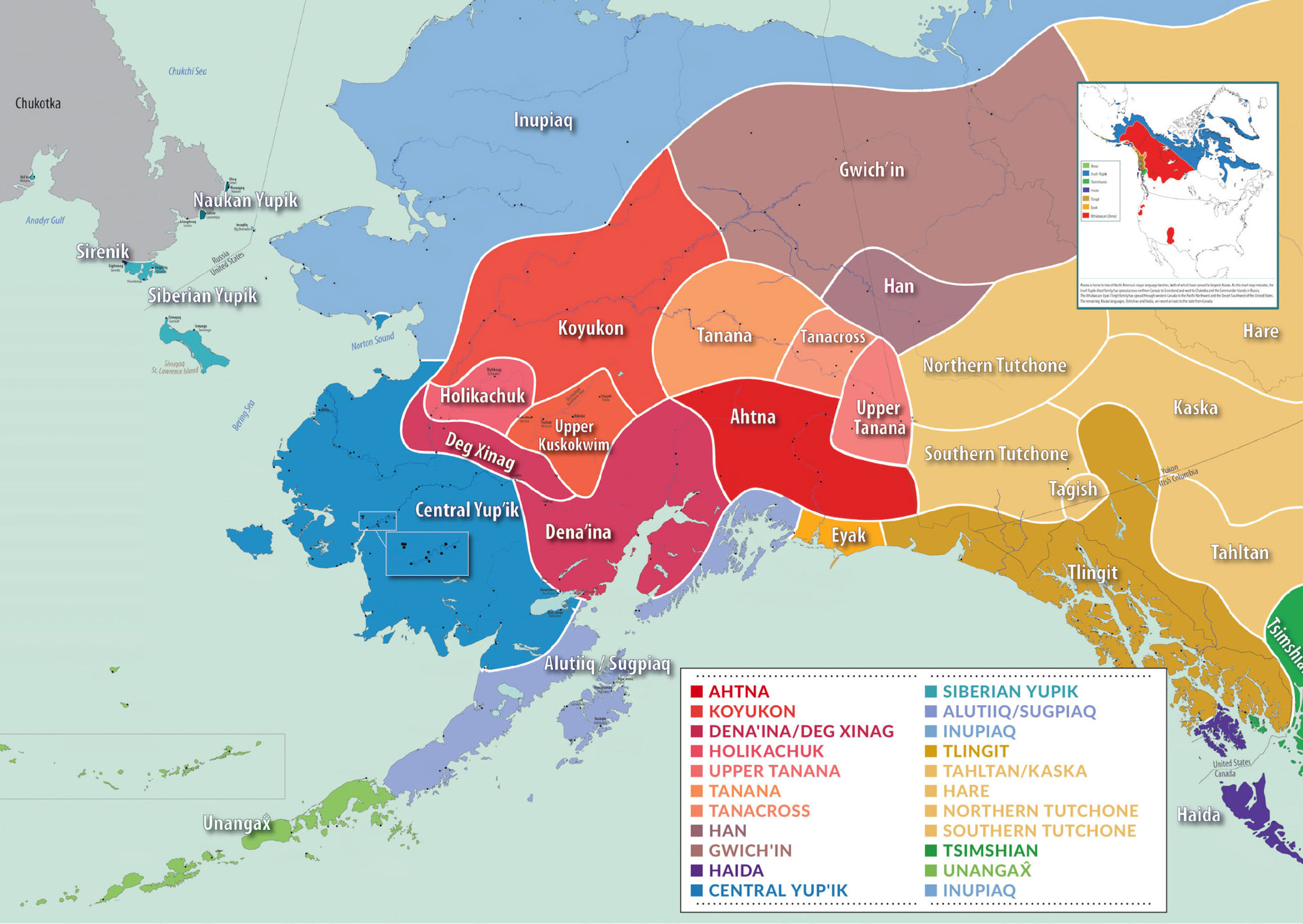

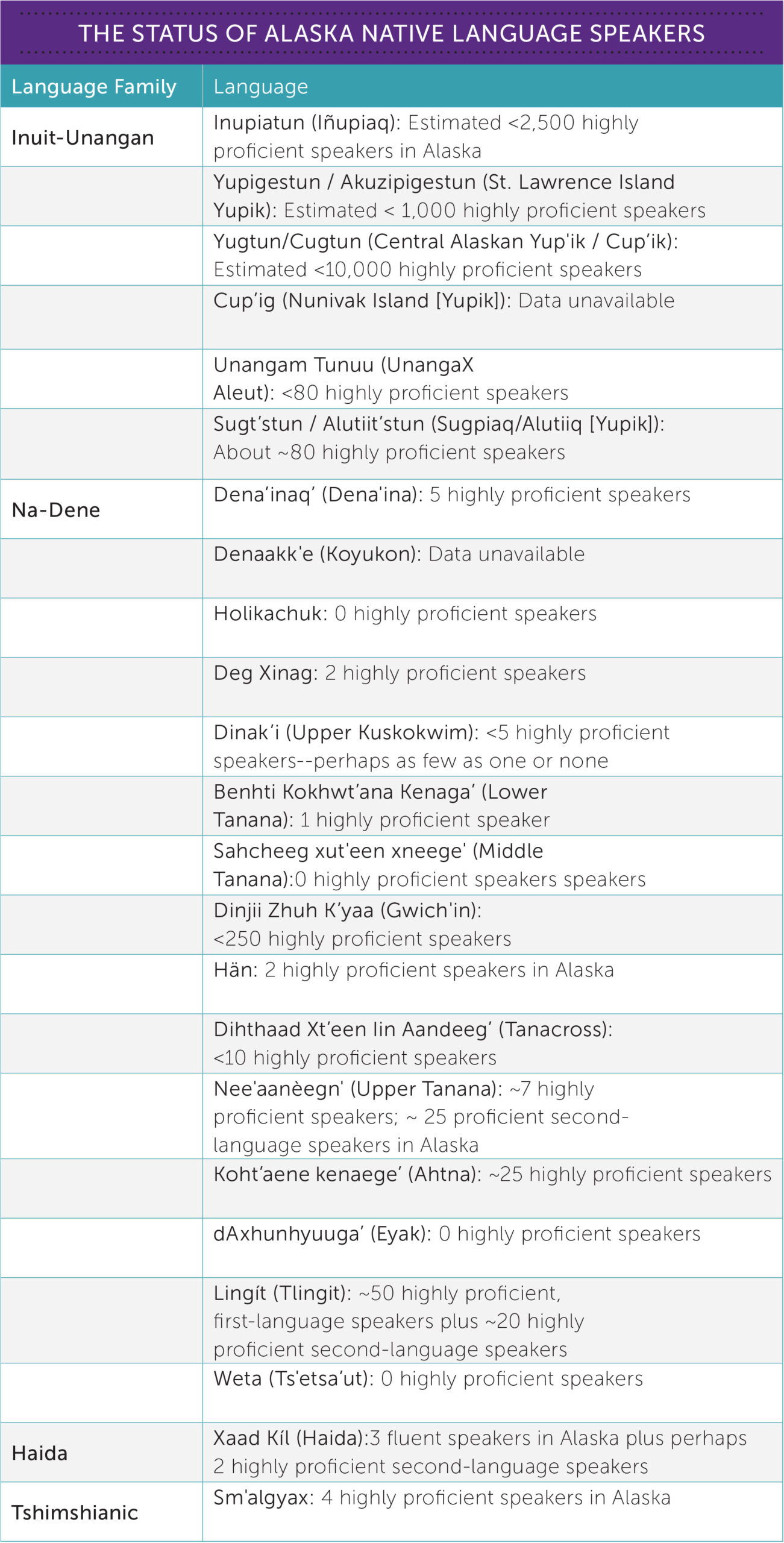

Today, no Alaska Native languages are considered “safe” or merely “vulnerable” as defined by the council.

“We tweaked the definitions in a few spots,” says Roy Mitchell, staff research analyst for ANLPAC. “We had labeled what was previously listed as extinct to dormant, meaning there are no conversational speakers left. The shift at the council is really pushing to not buy into negative labels. We’ve been using dormant for a few years now, rather than say there are no speakers left [or extinct].”

Mitchell is a linguistic anthropologist specializing in Iñupiaq and a PhD candidate at the University of California Berkeley. He has been a student of Alaska Native languages since 1976, supporting Alaska Native languages in many regions throughout Alaska.

Alaska Region Training & Technical Assistance Center

“The council has been asking for state government, both the executive and legislative branches, to actively make the survival of Alaska Native languages a high priority,” Mitchell says. “That continues to be a major issue. The state has and is continuing to do some things to improve the status of Alaska languages, but it is still nowhere close to the level that’s needed.”

T/TA Center Technical Assistance Manager Larry Kairaiuak, who is Yup’ik, worked in grant management for the private sector and state government before joining the federal office.

Alaska Region Training & Technical Assistance Center

ANA’s FY2021 appropriation was more than $57 million. In FY2020, ANA was able to provide approximately $47 million to community-based projects across the three main ANA programs: Social and Economic Development Strategies, Environmental Regulatory Enhancement, and Native Language Programs.

The share for language programs totaled $13.7 million, split between $6.8 million for Preservation and Maintenance (P&M), $5 million for language grants such as Esther Martinez Immersion, and $1.9 million for Native Languages Community Coordination Demonstration projects.

The ANA P&M program provides funding for projects to support assessments of the status of the Native languages as well as the planning, design, restoration, and implementation of Native language curriculum. Projects take place in urban, rural, and reservation settings through materials development, training for language teachers, and direct instruction in and outside of a classroom.

Unagam Tunuu Achigassalix, or Teach the Aleut Language, is a P&M project that the Aleutian Pribilof Island Association is working on. It connects several language learners with two speakers, working to increase the number of speakers in the Aleutian region. This project started right before the COVID-19 pandemic, so in-person classes did not occur. They immediately adjusted to a method of virtual meetings so that the program could carry on.

Tamamta Liitukut, or Everyone is Learning, from the Sun’aq Tribe of Kodiak, just completed a Native Language Community Coordination Demonstration project through ANA. It was a Kodiak Sugpiaq Alutiiq language education continuum project to increase the number of speakers and instruct young children at the same time.

“We want to see more projects funded throughout Alaska,” Kairaiuak says, “so that some of the challenges that our tribes and communities face can have a platform to improve the conditions that hinder us from growing and enhances the lives of our communities.”

In a review of language projects that ended between 2015 through 2020, ANA has supported eighty-seven different languages across the United States and Pacific Basin. ANA funded projects for eighty tribes and Alaska Native villages, thirty-five nonprofit organizations, eighteen K-12 schools, and eleven tribal colleges and universities.

Dzantik’i Heeni Middle School

“I received a grant called Haa Yoo X’atángi Deiyí: Our Language Pathway. This was through Sealaska Heritage Institute to go back to school,” Katasse says. “The program involved sending a cohort of people to go back to school at the University of Alaska Southeast and study Tlingit, Haida, and Tsimshian and learn to be teachers, resulting in a Type M Limited Teaching Certificate.”

The certificate in Indigenous Language Teaching prepared students to work in the growing language revitalization field, including within tribal organizations, tribal corporations, school districts, and nonprofit organizations.

Teacher

Dzantik’i Heeni Middle School

Alaska Native Language Center | Institute of Social and Economic Research

“In other language programs, a lot of times the revitalization efforts are centered around clubs or something after school,” Katasse says, “where parents can come and participate or something. Here I am teaching about 150 Tlingit language learners. With that many students, it’s a bit too many to also include parents. It’s a very popular program, right up there with gym, art, music, and now Tlingit.”

Katasse reaches his students in class using various games, both online and board games. The students can also earn class “money” by answering questions, and then use the tokens to buy candies, stickers, and other small gifts. Students are having fun and learning Tlingit along the way.

Next for Katasse is preparing for Tlingit II. “For the upcoming year and those students moving forward,” Katasse says, “I have to figure out what I’m going to teach them. For language learners in middle school especially, we’re playing games and keeping them engaged. We want them to want to come back.”

Katasse notes that some of his 150 students never spoke any Tlingit at all, and some are not Alaska Native of any kind. That doesn’t matter, he says.

“It was such a beautiful experience when I began hearing the Tlingit language start to overflow into the halls and out of the classroom,” Katasse says, adding, “I would hear them making fun of each other in Tlingit.” ![]()