Resolve Marine Alaska

Resolve Marine Alaska

omer has its halibut, the Kenai its kings, Bristol Bay is famous for its sockeye, and Southeast harvests herring. Far from Alaska’s 6,640 miles of coastline, though, anglers find plenty of opportunities for sport fishing. The Alaska Department of Fish & Game (ADF&G) counts an average of nearly 102,000 resident angler days each year in the Arctic/Yukon/Kuskokwim region, plus more than 44,000 non-resident angler days. And they’re not snagging salmon—at least, they have plenty of other options. Region III, which encompasses about 80 percent of the state, is home to thirty-seven freshwater and brackish water fish species, of which several are targeted as sport fish.

There’s burbot, referred to as the poor man’s lobster, an eel-looking fish with mottled skin ranging from black to gray to olive or even yellow. It’s popular with sport fishers mainly for its flavor. It is the only freshwater species of cod, which may be why it’s so good to eat. Unlike other freshwater fish, burbot spawn in mid-to-late winter, which makes them active during ice fishing season. “A lot of people use set lines for burbot in the winter,” says Andrew Gryska, Tanana area biologist for ADF&G. A relatively long-lived and slow-growing fish, burbot typically average three to five pounds, with some fish getting up to about eight pounds, which is not uncommon in the Yukon and Tanana rivers. Burbot live in rivers, both clear and glacial, and in many lakes throughout Alaska, but not in Southeast. The largest burbot sport fisheries occur in the Tanana River and lakes in the upper Tanana, Upper Copper, and Upper Susitna river drainages.

An Arctic char, which are the northernmost freshwater fish in the world.

Andy Gryska | ADF&G

Andy Gryska | ADF&G

Humpback whitefish is distinguished from other whitefishes by the hump behind the head of the adult fish. It’s a medium-sized fish that can grow to about 26 inches long. Another spearfishing fish, it’s typically dark brown to midnight blue dorsally, fades to silver on its sides, and has a white belly. It can be found throughout several water bodies within the Yukon River, Kuskokwim River, Tanana River, Kvichak River, Susitna River, Copper River drainages, as well as the Alsek River near Yakutat. Humpback whitefish have been known to spawn under ice in the Kuskokwim River as late as mid-November.

Broad whitefish is, well, broader than other whitefish species. It has an elongated body and silvery scales and typically weighs up to eleven pounds. It can be found in Alaska’s freshwater drainages of the Bering Sea, including the Yukon and Kuskokwim, and the drainages of the Chukchi Sea and the Arctic Ocean. Broad whitefish is generally spearfished and is an important subsistence fish in Alaska.

Round whitefish have rounded cigar-like bodies and pointed snouts. These fish rarely exceed 24 inches in length. They inhabit almost every type of river and freshwater habitat north of the Alaska Range.

Arctic char are the northernmost freshwater fish in the world. They are somewhat larger than Dolly Varden and have fewer and larger spots. They vary in color depending on the time of year and their environmental conditions and can grow up to 38 inches long and weigh up to thirty pounds. They spawn annually or every other year, and when spawning their lower body and lower fins are orange to red in color, with males more colorful than females. Arctic char are found in lakes in the Brooks Range, the Kigluaik Mountains north of Nome, the Kuskokwim Mountains, the Alaska Peninsula, Kenai Peninsula, Kodiak Island, and in a small area of Interior Alaska near Denali Park. ADF&G does not consider Arctic char as important a sport fish as Dolly Varden, which has greater numbers across a wider area.

Arctic grayling are one of the fish that attract anglers both from within and outside Alaska.

Andy Gryska | ADF&G

Andy Gryska | ADF&G

An Arctic grayling, the most widely found fish in Alaska’s interior.

Andy Gryska | ADF&G

Lake trout are closely related to rainbow trout and similar in shape, but their coloration is different: irregularly-shaped yellow or cream spots on a dark background. Lake trout typically grow to about twenty-five pounds, but they can be larger—the current record is forty-seven pounds. Lake trout are broadly distributed in northern and southern Alaska, but they are not found in the Yukon River basin. Unlike rainbow trout, lake trout spawn in the fall rather than spring, and these fish can live a long time. “Some of our oldest fish on the North Slope can be fifty years old,” says Scanlon, and ADF&G has recorded one individual that lived for sixty-two years. In deep, cold lakes, there’s a chance to catch a really large lake trout.

Andy Gryska | ADF&G

Lake trout are closely related to rainbow trout and similar in shape, but their coloration is different: irregularly-shaped yellow or cream spots on a dark background. Lake trout typically grow to about twenty-five pounds, but they can be larger—the current record is forty-seven pounds. Lake trout are broadly distributed in northern and southern Alaska, but they are not found in the Yukon River basin. Unlike rainbow trout, lake trout spawn in the fall rather than spring, and these fish can live a long time. “Some of our oldest fish on the North Slope can be fifty years old,” says Scanlon, and ADF&G has recorded one individual that lived for sixty-two years. In deep, cold lakes, there’s a chance to catch a really large lake trout.

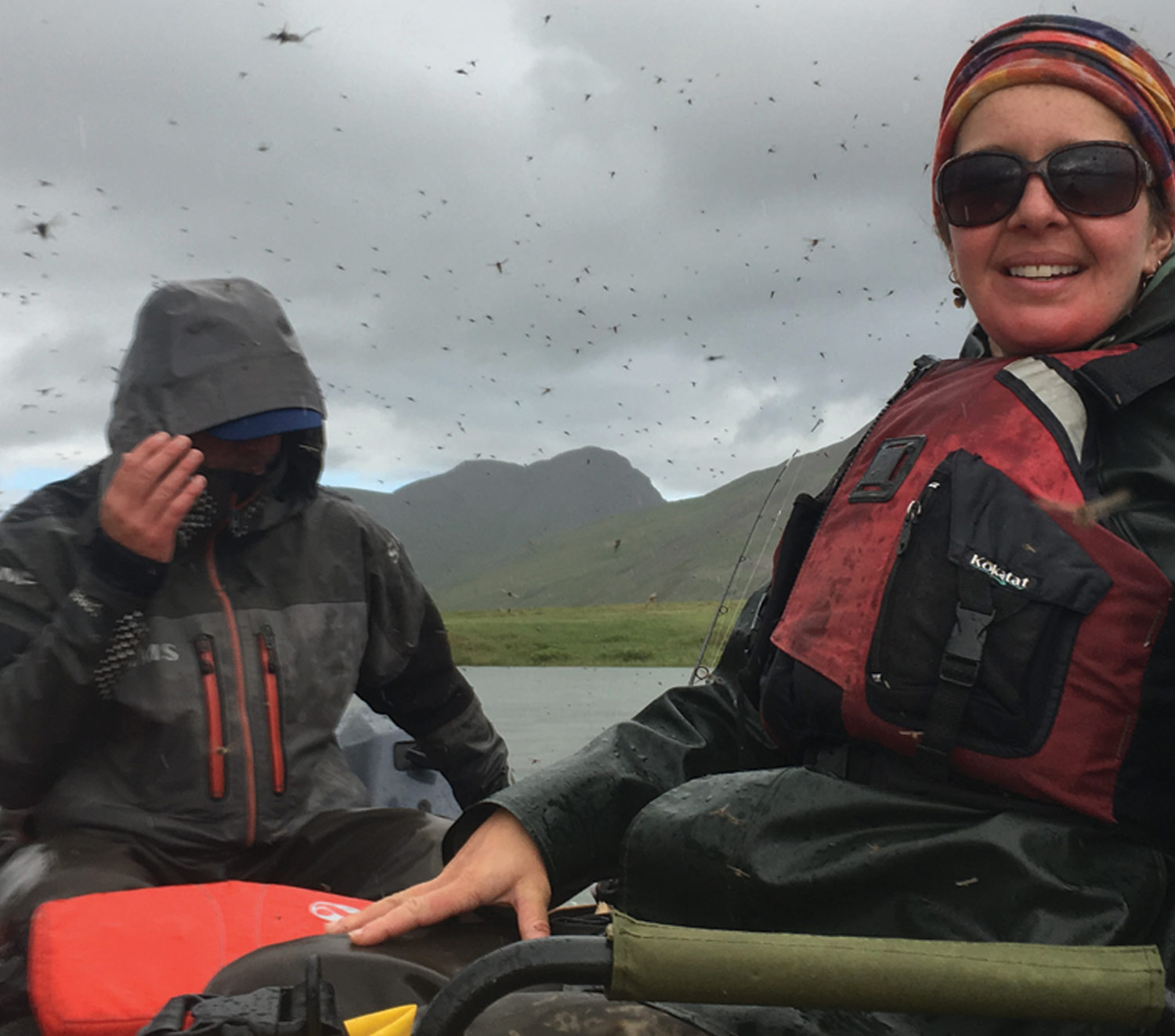

While the Kenai Peninsula and Katmai area earn top ranks from fly fishing experts, the Yukon River drainage is also a recommended destination for northern pike and sheefish.

Andy Gryska | ADF&G

Andy Gryska | ADF&G

Along with the five species of Pacific salmon, these six fish are considered the Grand Slam for Alaska fishermen. Anyone who catches a Dolly Varden, Arctic char, rainbow trout, lake trout, Arctic grayling, and northern pike, as well as a king, silver, red, pink, and chum salmon has achieved the summit of Alaska sport fishing. Crystal Creek Lodge in King Salmon advertises a week-long package during a window in July when all eleven species are present in the region, and any guest who achieves a Grand Slam within that week is duly honored.

Less ambitious anglers can be satisfied knowing that Alaska’s 3,000 streams and 3 million lakes, far from saltwater, offer a lifetime supply of worthy opponents. ![]()