Marine Mammal Huntress

A tale of a Native woman on an epic quest

By Hope Roberts

Surreel Saltwaters

hen times are hard I tell myself, “Where there is a will, there is a way.” I am a Tlingit-Gwich’in-Koyukon Alaska Native woman who owns a deep-sea fishing charter, Surreel Saltwaters. After twenty years in the Operating Engineers union, thanks to Local 3 in Hilo, Hawai’i, I have been built to work in an industry dominated by Caucasian males.

I have never felt accepted by many social arenas as a Native woman, and like my parents and their parents, I have been challenged.

My maternal grandfather was a child prisoner survivor who went to boarding school in Wrangell. My paternal grandfather passed from emphysema, which he contracted working as a laborer during the early pipeline days.

You can imagine how hard boarding school was on my maternal grandfather, a child under the age of 10, and the effect his experience had on my mother. Both my mother and grandfather succumbed to alcoholism, which led to cirrhosis of the liver.

Yet resilience is built in our DNA; where there is generational trauma there is also transformational grace.

I made myself accepted, I watched the people that I wanted to be like, and I have made myself into the person I wanted to be.

For years, I felt like my spirit was screaming to be on the coastal waters, and I did not know why. I had no idea that harvesting and learning to be a marine mammal huntress was embedded in my DNA memory. It is—I have never felt so at home before anywhere. Not when I harvested moose (with two little girls, one being a baby, in tow), not berry picking, not even fishing for salmon.

I knew in my heart that there were more individuals who felt like me and I was going to find them.

The Marine Mammal Protection Act allows Alaska Natives like the author to take sea otters, seals, polar bears, or whales for subsistence food or for making handicrafts. Harvest and trade of marine mammal parts is otherwise severely restricted.

Surreel Saltwaters

Surreel Saltwaters

I used to play outside across the street from a grocery store called Market Basket. I saw that many people did their weekly grocery shopping on the weekends and had a tough time carrying their bags three stories up. I saw a need to help people, so I did. I carried bags of groceries for people. At first, it was just out of kindness. When I was tipped five dollars for the first time, I realized it was a needed service. I began waiting outside the apartment buildings on the weekends to help people for tips, and then I would cross the four-lane road to buy a deli burrito, which I had been privileged to try once when we had an extra $0.69.

It was very rewarding, especially since by the end of the month a lot of times we would be out of food and food stamps. This is where my love for business began.

It is hard and seems hopeless at first when there is no one breaking the trail for you, but it is doable. While 84 percent of people born in poverty stay there, you can be the other 16 percent. On the other side of that statistic, I build my decolonized self through marine mammal harvesting, and I feel rich in that.

Before I started Surreel Saltwaters, I had never been on a fishing charter. Last year marked our fourth successful year in business.

After five fabulous sport fishing years, I wanted to share this healing time with other Alaska Native people who want to be on the waters.

I had for years planned on helping others learn to hunt on the water, but I could not figure out how until one day it clicked: just invite them.

In April 2022, I did just that. I asked a Tlingit elder, two scientists, and a board member who serves the Prince William Sound Native villages and natural resources departments to join me.

My dear friend had asked relentlessly in meetings to be taught to hunt, and I heard what she needed.

I was honored to show an Alaska Native leader where her ancestors roamed, where her spirit would be filled, and where we could speak freely without any outside influence that would, well, influence the conversations.

The day was wonderful: I saw half smiles turn into full-blown, life-changing joyous grins.

In the 281 years since the Russians first arrived, Alaska Native people have had to adapt to several outside influences without speaking Russian or English. Even after those years, approximately 70 percent of Alaska’s coastal living Natives are still more than one-quarter Alaska Native. This blood quantum being one of the stipulated rules for legally hunting marine mammals is a fair rule.

We should be reconnecting those who are hurting the most to their ancestors’ healing skill and art of marine mammal hunting. I am overjoyed to use my sport fishing infrastructure to do just that. To help others heal through marine mammal hunting, I continuously find ways to invite them along. I have also started researching ways to fund the harvests, as it can be costly: the hides are expensive to tan, and the meat and blubber need to be processed in a semi-protected covering when we bring them to land to teach others. Protected, you see, from bears, the dominant species in our hunting area.

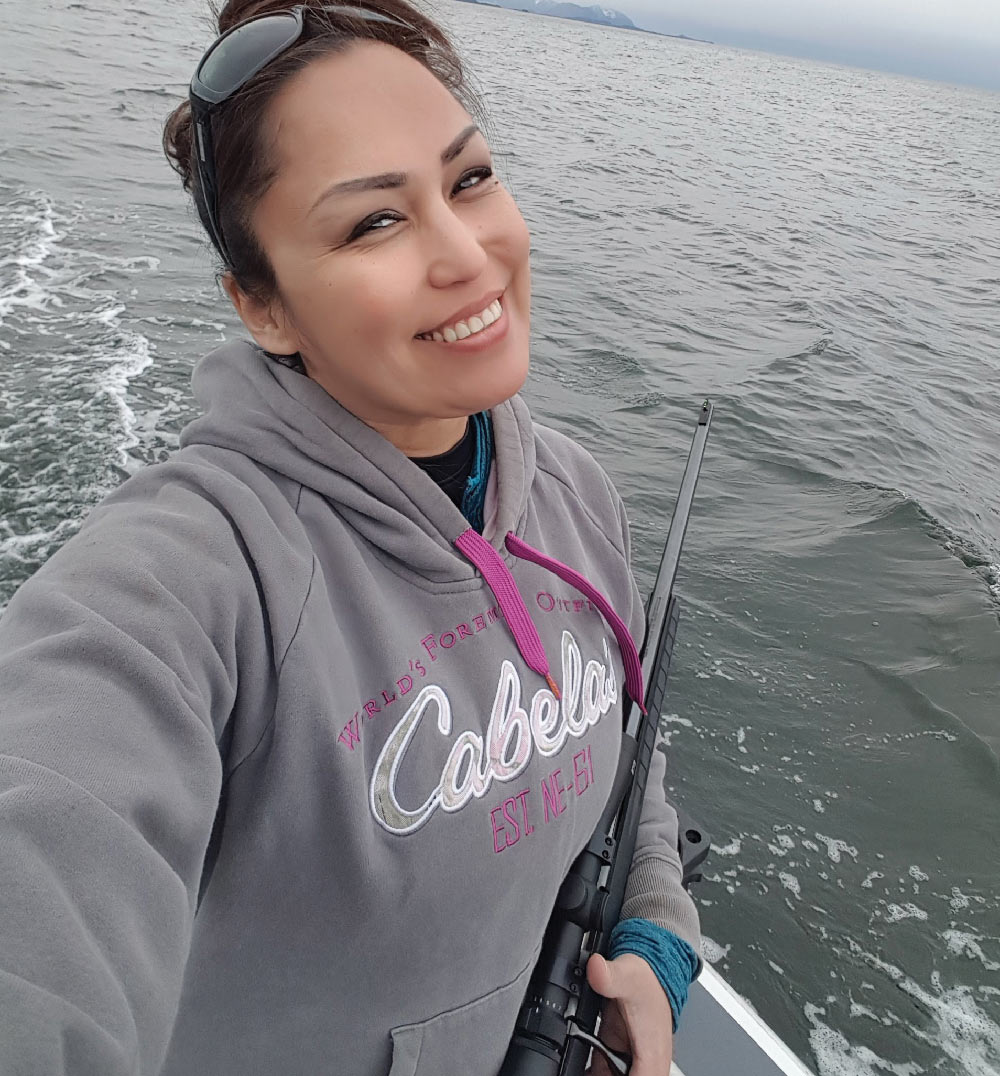

Hope Roberts (top) uses infrastructure and resources from her sport fishing charter business, Surreel Saltwaters, to help other Alaska Natives experience marine mammal hunting.

Surreel Saltwaters

Surreel Saltwaters

I became a foster parent in 2020. There are so many issues that kids in state custody face, but the one that stands out to me, that I was strongly drawn to, is the lack of Indigenous foods provided to the 1,991 Native children in foster care. As of publication, that is 67 percent of the population of children in foster care in Alaska. Most of those children are in the Southcentral region, where I live.

Food is life, Indigenous food is power, it is healing. My solve will create an online platform and use that, as well as modern and primitive tools, to normalize feeding children in the foster system their Indigenous “soul food.”

And I can’t stop here. I also wrote to the Na’ah Illahee Fund in Seattle about keeping marine mammal harvesting Indigenous, which helps those who need it, using the ancestral art for good and not Western ideal profit.

The American Indian women’s philanthropist group awarded my project one of five fellowships, and I’m planning to make a short documentary about the project in the future.

Many other Alaska Natives grew up with parents struggling with mental health and/or substance abuse who have no connections to and lack skill and time on cultural waters, participating in the cultural harvesting of marine mammals.

My history, my various businesses, and my business degree helps me help others in this respect. Where there is a will, there’s a way. ![]()