or decades, the Red Devil Mine in the Middle Kuskokwim River area has leaked mercury from its site, but remediation is on its way.

“While it’s not clear if this is the largest mining remediation ever done in Alaska, it’s certainly a large remediation,” says Public Affairs Specialist Gordon “Scott” Claggett of the US Bureau of Land Management (BLM) Alaska. “210,000 cubic yards of contaminated tailings and material will be excavated and consolidated in an onsite repository.”

The mine is on land managed by BLM, and the agency is seeking $40 million for the cleanup.

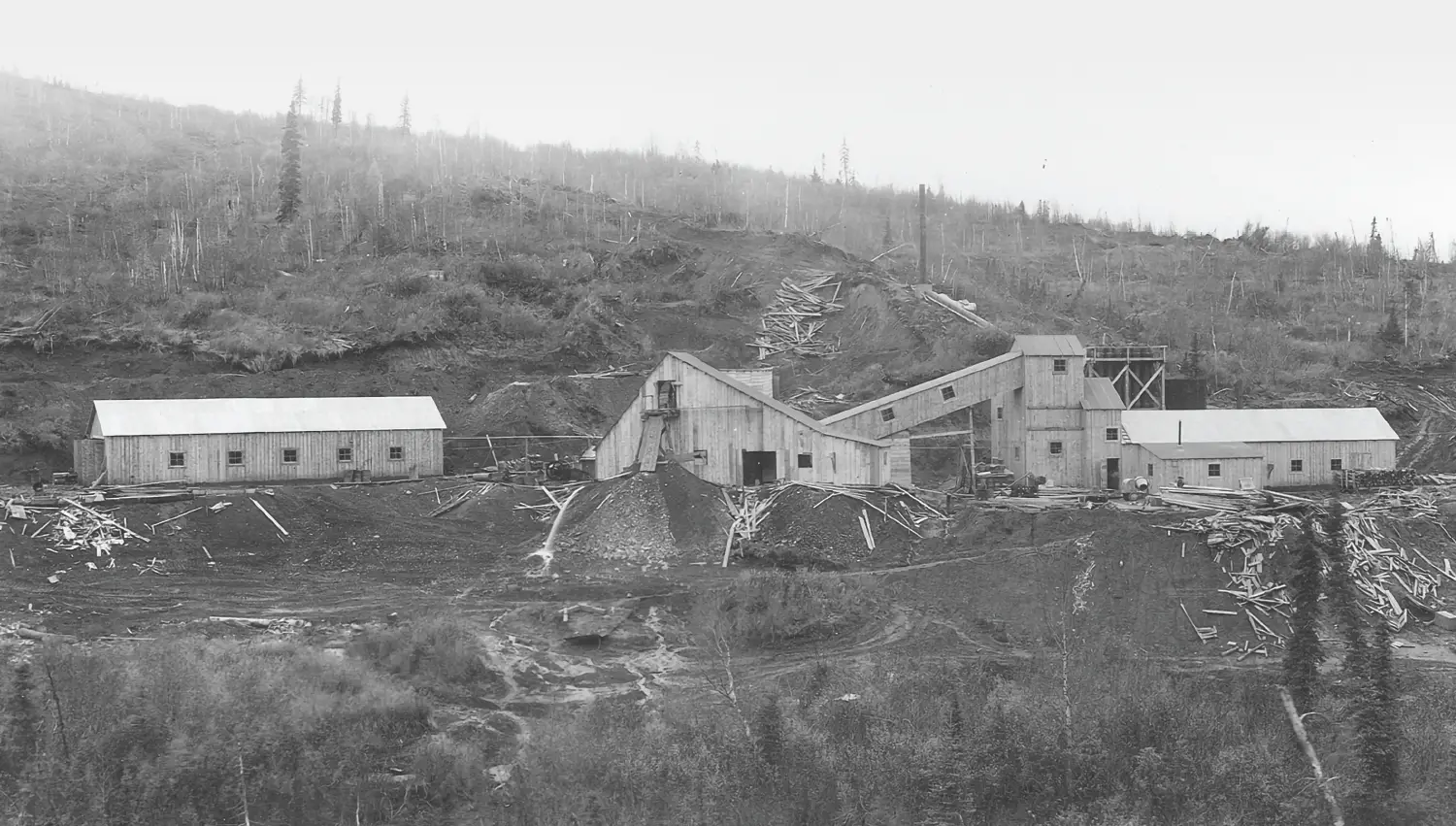

Mining began in 1933, and by 1939 mercury ore was being mined from creek sediments and overburden. Overburden is the rock or soil layer that needs to be removed to access the ore being mined. Mining the overburden also released arsenic and antimony.

Mercury was used in gold mining, as an amalgam that separated gold from its surrounding rock and then was burned away. With the advent of World War II, mercury became a key component of detonators for ammunition and explosives, as well as an ingredient in tracer bullets. At the time, mercury was also used in thermometers.

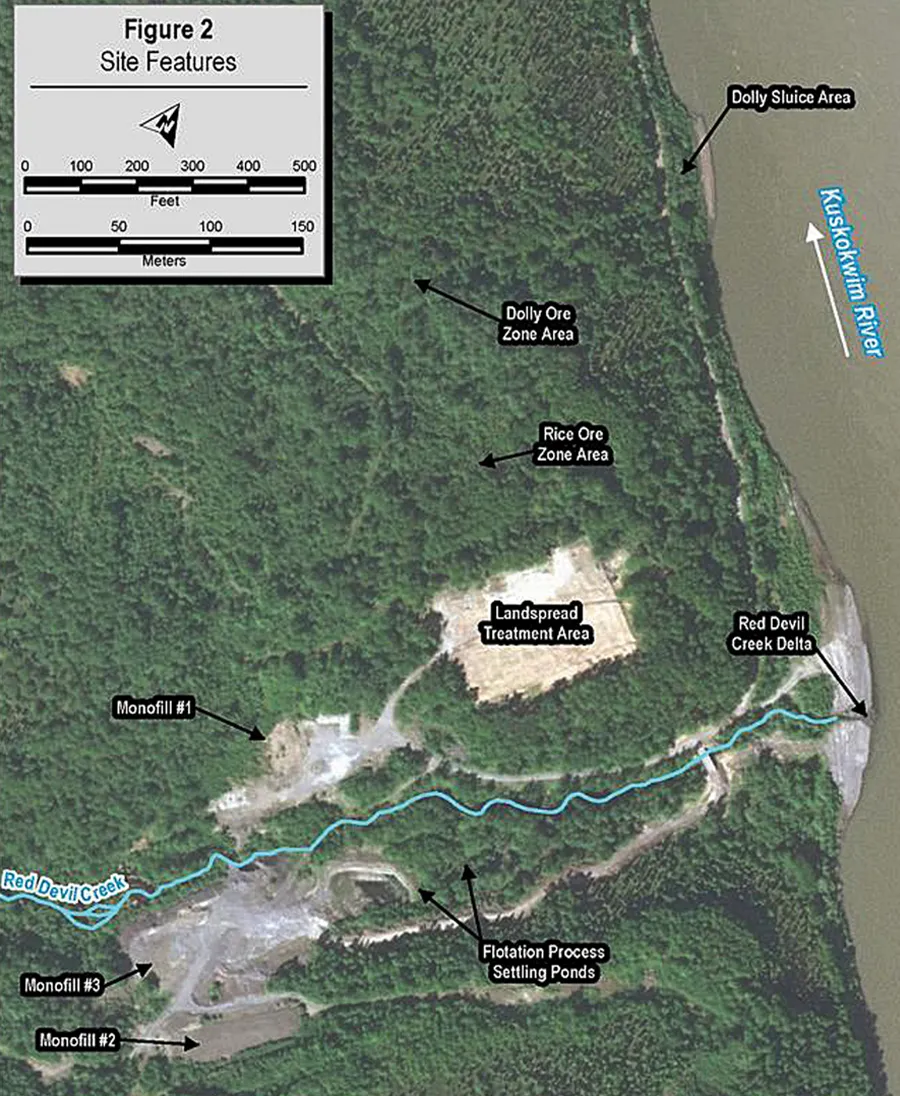

Red Devil Mine operated continuously until 1946, when the mercury price dropped. While production slowed, a 40-ton rotary kiln was installed to process the mercury thermally. Burned ore, or tailings, and waste rock were released into the drainage channel of Red Devil Creek.

Production resumed in 1952 and continued for two years until a fire burned down the mill equipment. Extensive surface exploration and mining continued after 1956, with waste material from a hydraulic sluice operation washing down a gully toward the Kuskokwim River, creating the Dolly Sluice Area Delta on the river.

Afterward, a modern mercury furnace was built. Open pit mining began in 1969. By 1970, the Red Devil Mine was Alaska’s largest mercury producer, and it was one of the largest in the United States. The mine continued operating until its final closure in 1971. All the while, tailings were dumped into Red Devil Creek, just upstream from the village of Red Devil.

US Bureau of Land Management

In the late ‘80s, the claim owners failed to file necessary information to maintain their claims, and BLM issued decisions concluding that the claims were abandoned in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s.

“The BLM was not able to locate a responsible party to assist with cleanup,” says Claggett.

BLM’s land law examiners reported that the land under the mine site was selected by Sleetmute Limited village corporation on November 18, 1974. Sleetmute Limited merged with The Kuskokwim Corporation on April 25, 1977, and The Kuskokwim Corporation is the successor in interest for all land conveyances.

As for subsurface, “Subsurface lands under village selections were not selected by the regional corporations,” Claggett says. “They are automatically conveyed to the regional corporations upon conveyance to the village corporations, and no physical file exists. All tracking would be done through our online systems like Mineral & Land Records System, and a subsurface patent would be issued. There would be no standalone Calista [Corporation] selection in the mine site.”

With private ownership ambiguous, BLM is proceeding with cleanup on its own. Somebody must, or else the contamination is liable to cause harm.

Aware of the dangers of bioaccumulative contaminants to fish, animals, and people, the Alaska Division of Environmental Health maintains the Fish Monitoring Program to track a range of trace metals (including mercury) and persistent organic pollutants among the 114 species of Alaska fish sampled.

Most species of Alaska fish, including all five wild salmon species, contained very low mercury levels that are not of health concern, according to a 2007 report focusing primarily on the prevalence of mercury and persistent organic pollutants. However, the report showed a small number of Alaska fish species had high enough mercury levels to recommend that women who are or can become pregnant, nursing mothers, and young children limit consumption of those fish species.

Of 359 women of childbearing age from fifty-one Alaska communities tested as part of a state Mercury Biomonitoring Program from 2002 to 2006, none had hair mercury levels of clinical or public health concern due to eating Alaska fish.

There are ways to reduce risk of consuming mercury or other contaminants. The state recommends eating smaller, younger fish. They generally have less mercury than those that are long-lived or fish that eat other fish. Larger fish are often breeding females, so keeping them in the ocean helps sustain fish populations and helps prevent overfishing, as a bonus.

Careful menu selection is a simple preventative measure, orders of magnitude simpler than the massive effort required to keep mercury out of the food chain to begin with.

The bureau considered the option of disposing of contaminated material away from the site, which would reduce the need for long-term monitoring, but the transport would raise the estimated cost to nearly $200 million. The low-cost action would be to erect a 12-foot-tall fence for less than $1 million, but BLM opted for excavation and onsite disposal for about $30 million.

BLM determined that it would target antimony, arsenic, and mercury in tailings, waste rock, soil, and Red Devil Creek sediments to restore polluted areas to a level that is protective of human health and the environment. The restoration will be complete when cleanup levels are met for site-related contaminants in tailings and waste rock, contaminated soil, groundwater, sediments in Red Devil Creek, and nearshore sediments in the Kuskokwim River.

The cleanup is expected to take thirty years, with periodic analysis to look for possible problems and take corrective actions. BLM will share monitoring data with the Alaska Department of Environmental Conservation and will formally review the data every five years, specifically to evaluate the plan’s effectiveness and address possible failures, if necessary.

“The next step in this process is a Value Engineering Study, which is a procedural study conducted prior to a request for project funding. BLM is currently working on a solicitation for that study,” says Claggett. “Once that step is completed, BLM will pursue funding to implement the remediation actions outlined in the decision. The pace of implementation will depend upon funding received.”

The published timeline could have personnel working on the Red Devil Mine cleanup who are not yet born. And by the time the job is finished in the 2050s, few people will still be alive who were around last time it produced any commercial quantity of mercury. Yet the job is worth doing.

BLM Alaska State Director Steve Cohn says, “We look forward to working with tribes, Alaska Native corporations, the state, and others to implement this plan to the benefit of the lands and communities.”