yanide and other waste spilled in June from Victoria Gold Corporation’s Eagle Gold Mine. The mine opened in 2018 near the village of Mayo, about 100 miles east of Dawson City. Although nearly as far away from the international border as Fairbanks is, what happens in Mayo doesn’t stay there. Mayo sits on the Stewart River, a tributary of the Yukon River that flows into Alaska.

Mary Catharine Martin, communications director for Juneau-based environmental group SalmonState, wasn’t exactly surprised that Eagle’s heap leach pad failed.

“The risks were made clear by Canada’s Mount Polley Mine waste dam disaster in 2014. Afterwards, experts estimated that two mine waste dams in British Columbia will fail every ten years, on average,” Martin says.

“For over a decade, the Alaska congressional delegation has expressed grave concerns about the longstanding impacts and future threats of abandoned, developing, and operating mine projects located in British Columbia near the Canadian headwaters of Southeast Alaska’s rivers,” the letter stated. “Under three different presidents, our delegation has pushed for the Department of State to secure binding protections and financial assurances for the transboundary Taku, Stikine, and Unuk rivers that flow from BC into Southeast Alaska and the Tongass National Forest.”

The letter also noted the cyanide spill at the Eagle Gold Mine.

“Without unified action from the executive branch, Canadian mining activity in this region will increasingly endanger US communities and resources, such as salmon, without any mechanism for recourse or compensation,” the delegation stated.

The expense of cleaning up the Eagle spill put Victoria Gold Corporation into receivership. That court order wiped out the value of company shares, so the board of directors resigned en masse in August. Victoria Gold ceased to operate, and the Yukon government took over responsibility for site rehabilitation.

Chris Miller | Salmon Beyond Borders

Chris Miller | Salmon Beyond Borders

Chris Miller | Salmon Beyond Borders

New Polaris is almost within sight of the Tulsequah Chief mine just 20 miles from the Alaska border near Juneau. Extracting zinc, copper, and lead in the ‘50s, the long-abandoned mine has leaked rusty, acidic runoff into a major salmon-producing tributary of the Taku River for almost sixty-seven years.

“Spills or mine failures in headwaters, as have happened recently elsewhere, could be catastrophic to wild salmon ecosystems,” says Will Patric, executive director of Rivers Without Borders.

The nonprofit has staff in Juneau and Petersburg as well as Victoria, British Columbia and northwestern Washington. Its stated mission is to protect the ecological and cultural values of the transboundary watershed region.

The group is more specialized than SalmonState, which gives attention to ocean fisheries and watersheds entirely within Alaska. But transboundary issues are also on SalmonState’s radar.

“One enormous threat to wild salmon and Alaskan jobs and ways of life is the storage of acid-creating mining waste behind failure-prone dams that must stay in place and intact forever in order not to contaminate our river systems,” says Martin. “Many of these structures, and mine sites, also require maintenance for hundreds of years, which is implausible, to say the least.”

Martin believes that Canada’s standards are lower than in Alaska, especially by allowing mine projects to proceed without the developers posting the money to clean up problems later.

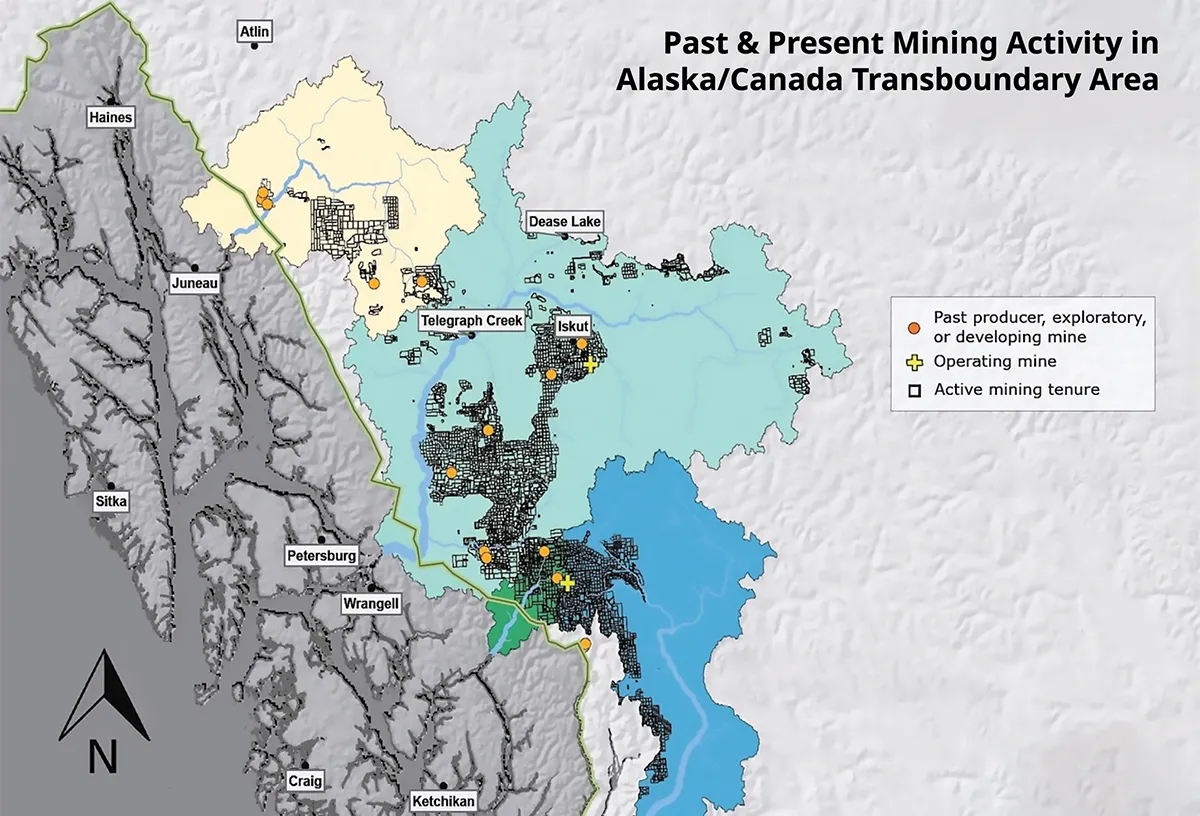

“In the transboundary region of British Columbia, Canada, and Southeast Alaska—the birthplace of the mighty Taku, Stikine, and Unuk rivers—more than 100 Canadian mines are in some stage of exploration, abandonment, operation, or development,” Martin says. “Most of them would require mine waste dams. They are also massive—some would be some of the largest mines in the world—and despite the fact that claims take up almost 90 percent of BC’s side of the Unuk River, there is currently no analysis of cumulative impacts.”

Fed by the pulse of salmon, the ecosystem sustained Alaska Native people for thousands of years, and the environment continues to sustain the economies of villages and towns.

“The T’aakū (Taku), Shtax’héen (Stikine), and Jóonax (Unuk) watersheds, which flow from the glaciated boreal forests of northern British Columbia into the temperate rainforest of Southeast Alaska, total about 35,000 square miles of some of the last remaining wild salmon habitat left on Earth,” reports Salmon Beyond Borders, the transboundary-focused campaign of SalmonState.

The campaign works with fishermen, business owners, community leaders, and concerned citizens alongside Native peoples on both sides of the Alaska-British Columbia border to defend and sustain transboundary wild salmon rivers, jobs, and subsistence way of life.

“SalmonState works to keep Alaska a place where wild salmon and wild salmon ways of life continue to thrive,” says Martin, “which means we work toward the protection of the things we know wild salmon need—like clear, clean, cold freshwater habitat and precautionary, ecosystem-based management. These things are essential to a future in which we all have wild salmon in our backyard streams, on our plates, in our smokehouses, and in our lives.”

The governments recommended establishing a collaborative governance body to develop and report on an action plan to reduce and mitigate the impacts of water pollution in the watershed to protect the people and species that depend on this river system.

Established under the Boundary Waters Treaty of 1909 between Canada and the United States, the IJC employs joint science-based fact-finding as a foundation for building consensus and determining appropriate action.

While this watershed is far from the Alaska border, the IJC action becomes a precedent that affects Alaska.

Guy Archibald, executive director of the Southeast Alaska Indigenous Transboundary Commission (SEITC), considers the move a real breakthrough. “It validates the tribes’ knowledge and role in environmental stewardship,” Archibald says. “This is the first time an IJC referral includes tribes and considers pollution pathways in cultural foods.”

In late August, the annual Transboundary Mining Conference “Our Land/Our Way of Life” met in Juneau for the third year hosted by Central Council of the Tlingit and Haida Tribes of Alaska, along with the Upper Columbia United Tribes and the SEITC.

It brought together Indigenous leaders from Alaska, Washington, Idaho, Montana, and British Columbia to meet with government officials and community partners to discuss solutions for the transboundary governance of each country.

“I think the reason I’m here is because about five minutes after IJC got the Elk reference I said, ‘Holy smokes, this is historic,’” said Merrell-Ann Phare, the current IJC Canadian commissioner, during a keynote speech to the conference. “While other collaborative efforts between stakeholders have occurred, this transboundary kind of thing has not happened anywhere else.”

Phare added, “It is important you never go back from this, right? This is now a new bar.”

SalmonState also welcomed the historic agreement.

“Over the years, it has become clear that Canada’s irresponsibly regulated gold mining boom is not just a threat to Southeast Alaska; it is a threat to the health of all communities, river systems, and fish populations that lie downstream,” Martin says.

Martin believes that an IJC referral is the solution by bringing governments and tribes to the table under the Boundary Waters Treaty. Martin says, “That treaty makes clear that neither country should be contaminating river systems to the detriment of those on the other side of the border.”

Funding for reclamation and clean up in British Columbia faces more than $1 billion Canadian ($736,349,900 US) shortfall and does not analyze the combined effects from multiple mines.

British Columbia has permitted 20 percent of transboundary watersheds to be staked with mineral claims, including almost 90 percent of the British Columbia side of the Unuk watershed and virtually all lands adjacent to the Iskut River, the Stikine River’s largest tributary.

While the Pacific Salmon Treaty allocates an equal share of the salmon that run the rivers between the two countries, each country needs to share information on mining activity.

“Large scale mining development, particularly as proposed on the Canadian side of the Alaska–BC transboundary watersheds, is the biggest immediate threat to Alaska fisheries and especially salmon habitat,” says Patric. “The development itself, introducing more development into remote intact regions, would degrade habitat.”

While removing dams and other impediments to migrating salmon does occur, the organizations’ main work centers on education and publicizing the situation. And there are the legal challenges. SEITC is represented by Earthjustice, a nonprofit environmental law organization.

Archibald is optimistic that legal challenges would be successful in protecting the rivers and Native rights.

“For the most part, the courts operate free from the influence of special interest groups that protect their monopoly on political and agency decisions. What those groups see as aspirational words, the courts view as binding social agreements,” he says. “The trajectory has always been to advance human rights, not deny them. Canada saw the result of denying Indigenous people’s human rights earlier in its history. It caused a stain Canada has been trying to correct ever since.”