laska seafood has so much to offer,” says Ashley Heimbigner. “It’s often a game of choosing which messages are best for the audience.”

Choosing messages is Heimbigner’s job as communications director for the Alaska Seafood Marketing Institute (ASMI). The public/private partnership, established by state statute in 1981, marked its 40th anniversary last year by revamping its alaskaseafood.org website to deliver its message more effectively. In addition to becoming more mobile friendly, the redesign streamlined access to ASMI’s recipe library.

“It was timely with the pandemic because more and more people were looking for information about what they were eating and recipes online, as we were all at home cooking,” Heimbigner says.

Website visitors might see suggestions for products they would not otherwise have bought. For example, potato latkes with Alaska salmon roe can be made with ingredients most home chefs keep in their cupboards, save one (or two, if the latkes are fried in duck fat, as directed). Salmon eggs would send the cook to the supermarket or Asian grocery.

“Based on insight that salmon roe is becoming more popular in the US domestic market, we worked with a chef to create a series of salmon roe recipes,” Heimbigner says. This accomplishes two of ASMI’s immediate goals: building demand for all parts of a fish, thus getting more value out of the catch, and creating a market to absorb the bonanza of Bristol Bay sockeye, which just saw a record harvest.

Processors and harvesters pay a self-assessment to ASMI, and the institute also leverages federal grants for its research and marketing. Those efforts range from designating January as “Wild Alaska Seafood Month” in Europe—starting this year and, with luck, again in 2023—to recommending fish as a replacement for Christmas ham or a fat goose at the center of winter holiday meals. Heimbigner says ASMI began gearing up six months in advance for next spring’s Lent, when Roman Catholics substitute fish for meat on the six Fridays before Easter.

This month, ASMI observes its own holiday, of sorts, with the return of the All Hands on Deck conference. Meeting in person after two years of virtual alternatives, ASMI is hosting the event at Alyeska Resort in Girdwood on November 9, 10, and 11. The conference lets the wider seafood industry and general public learn how each fishery is performing and how ASMI is coordinating the marketing of Alaska brands.

For all that, All Hands on Deck is merely a tune-up before the major opus the following week.

AFDF

AFDF

The Seahawks aren’t playing a home game the weekend of November 17, yet Seattle’s Lumen Field is drawing a crowd to the adjacent event center for the Pacific Marine Expo. That event is the stage for the annual Symphony of Seafood, presented by the Alaska Fisheries Development Foundation (AFDF).

Just as ASMI is a creation of state law, AFDF formed as the result of federal law, the 1976 Magnuson-Stevens Fisheries Act. The nonprofit coalition develops products, equipment, and techniques for the benefit of harvesters, processors, and coastal communities. Marketing is a small part of its charter, and the Symphony of Seafood is its most visible endeavor.

By mounting a competition, AFDF draws attention to products manufactured with Alaska seafood as a key ingredient. Entries include retail brands as well as products aimed at the food service sector.

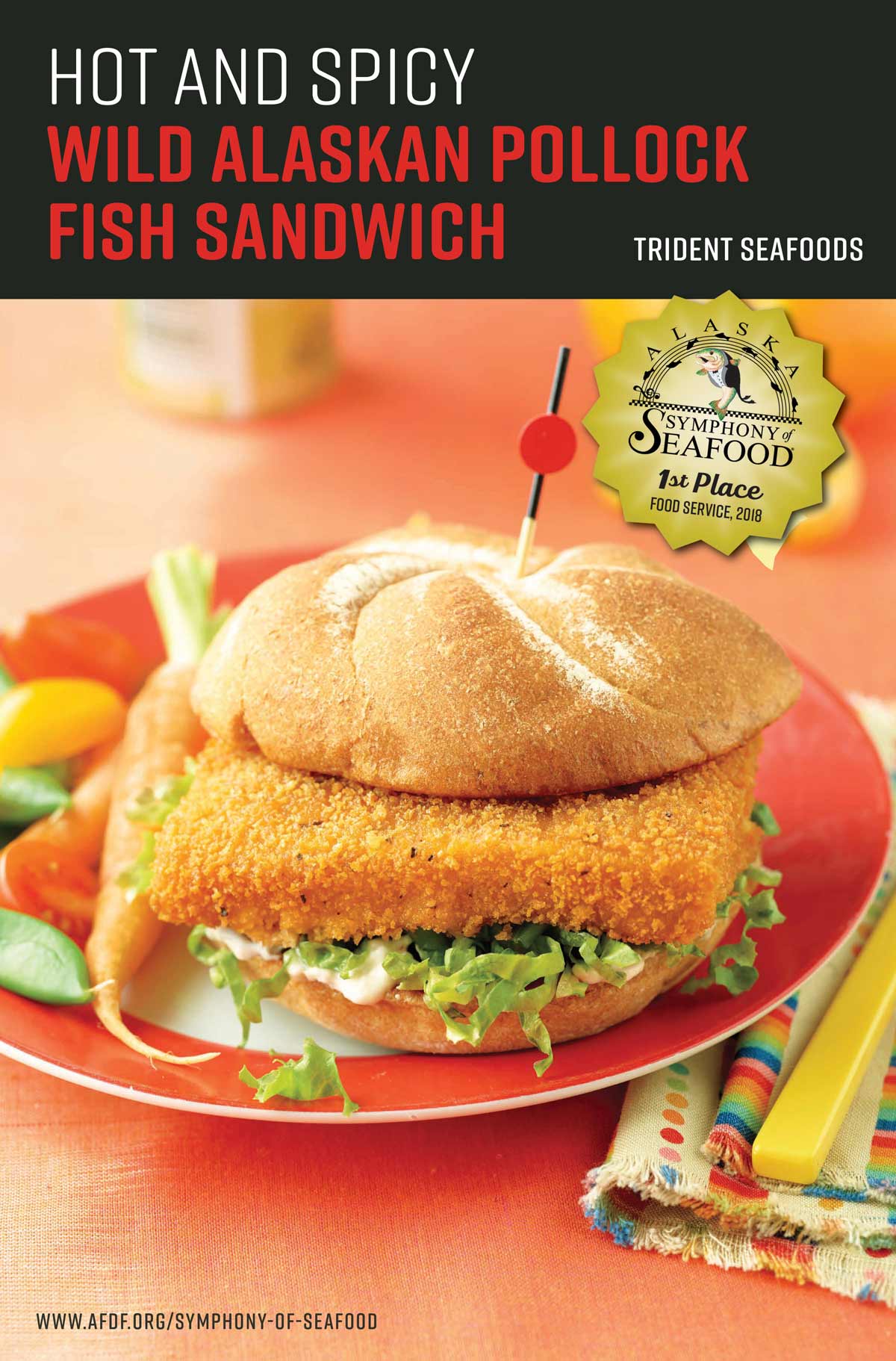

“Food service is marketing to hotels and institutions like colleges,” explains Julie Cisco, executive administrator of AFDF. “The packaging, of course, is different: it’s bulk. They need the longevity, and they need it to be simple.”

Entries don’t necessarily have to be food. Last year, the grand prize went to Deep Blue Sea bath soak by Waterbody, which was entered in the “Beyond the Plate” category. Past entries also include pet treats, fish skin jewelry, and chemical derivatives from crustacean shells.

Ashley Heimbigner, Communications Director, Alaska Seafood Marketing Institute

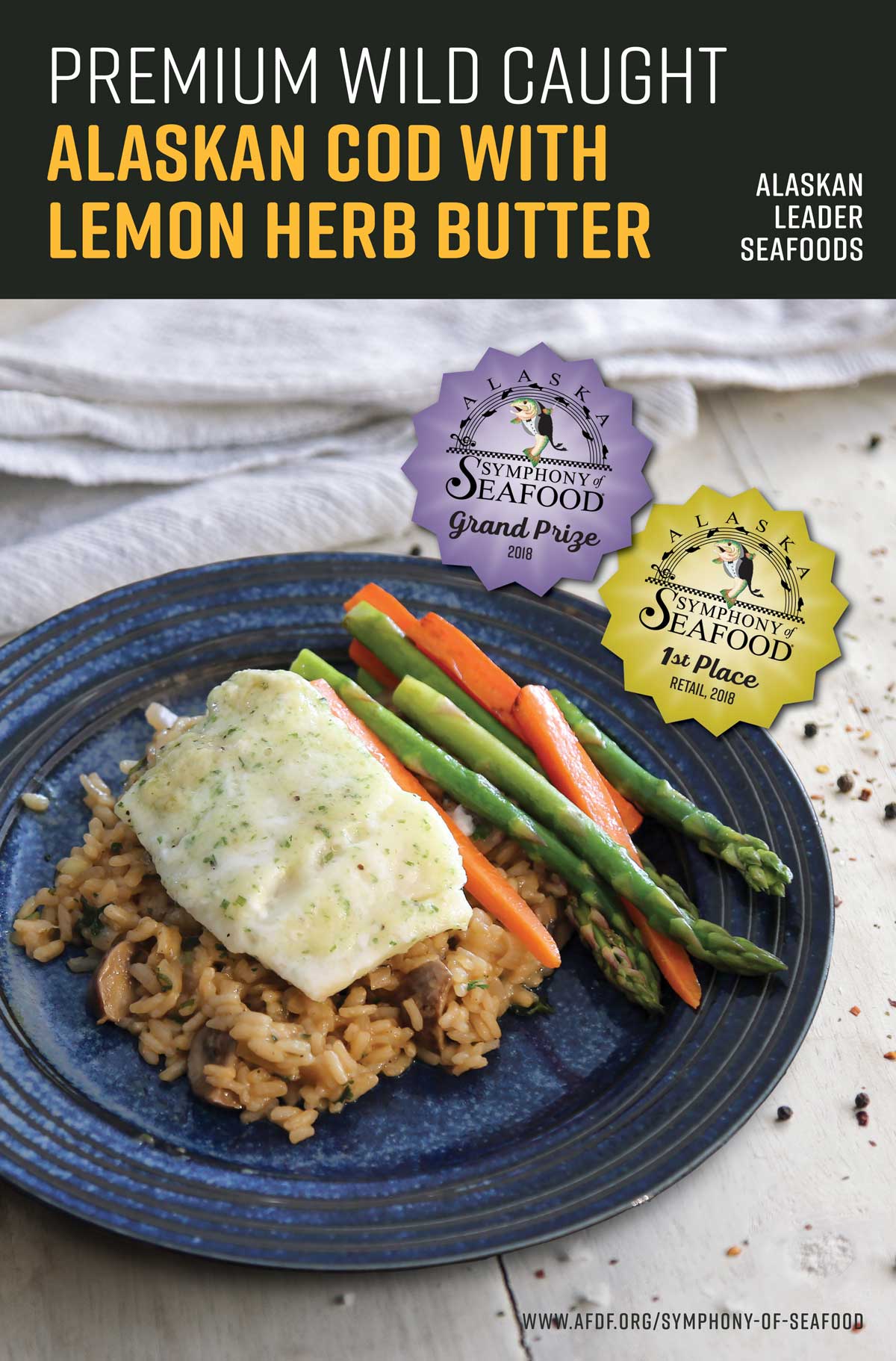

The event began in 1998 as the Symphony of Salmon before expanding to include other species (although shellfish are still largely absent). Salmon products dominated until 2007, when a cold smoked halibut won the grand prize. Lately, salmon has been shut out of the top spot by hot sauce made with kelp, packaged cod in lemon herb butter, and protein noodles made with Alaska pollock. Outside of the main categories, special prizes honor the best salmon and best whitefish, where halibut, cod, and pollock compete against each other.

“We definitely have some amazing fish in the Alaska whitefish basket, so it makes for great competition,” says Craig Morris, CEO of Genuine Alaska Pollock Producers (GAPP). “It makes Alaska pollock, our industry, more innovative and work even harder.”

Strictly speaking, Alaska pollock (also known as walleye pollock) is a type of cod; the Food and Drug Administration recognized in 2014 that it belongs in the cod genus. The common name remains in use, even for Gadus chalcogrammus caught elsewhere in the North Pacific, outside of Alaska waters. In GAPP’s name, “Alaska” modifies “pollock,” not “producers.” In fact, the nonprofit is not in Alaska at all, but in Seattle.

The Emerald City doesn’t get all the glory of the Symphony of Seafood, though; Alaska reserves the privilege of announcing the winners. After the initial round of judging at the Pacific Marine Expo, the scene will shift to Juneau during the legislative session in February. Another round of judging will name a Juneau’s Choice award, and final scores will be tallied. Winners in the three main categories, as well as the Grand Prize winner and a special sockeye salmon selection by the Bristol Bay Regional Seafood Development Association, will be flown to Boston in March to display their products at Seafood Expo North America.

At that forum, Cisco says, “hopefully you get the eye of someone you didn’t, or couldn’t, reach before.”

The song of salmon has climbed the charts, growing in popularity over the past decade to surpass canned tuna as the second most consumed seafood in the United States, after shrimp. Alaska pollock is in a struggle for fourth place against freshwater tilapia, which is raised mainly in fish farms whereas pollock had never been farmed until a few years ago.

Wildness is one of the key themes of Alaska seafood marketing. A wild catch comes at a literal price, though, so marketing must push back against cheaper farmed alternatives.

“A big part of what we do is connecting the product origin to the point of purchase,” Heimbigner says. “If that’s not there, then it’s difficult for consumers to understand the price point that comes with Alaska seafood.”

Through a nationwide survey followed by focus groups, GAPP has learned which messages make consumers hungry for Alaska pollock.

“This fish has fifty factual attributes, but packages of food or menus can’t be like a NASCAR with fifty stickers on ‘em,” Morris says. “You have to really distill that down to the attributes that are the most impactful.”

That distillation arrived at two attributes of pollock itself—its mild taste and nutritional value—and three related to where the fish is caught: wildness, sustainability, and its point of origin. “That provenance is very important to consumers, and it carries that halo that our partners with the Alaska Seafood Marketing Institute work so hard to build,” Morris says.

Although taste and quality drive most purchase decisions, Heimbigner says ASMI has learned that shoppers want to understand where their food comes from and who harvested it. “People want to feel good about the product they’re eating, both in terms of how it’s good for their body and that they’re not making an impact on the environment,” she says.

When ASMI isn’t figuring out what consumers want and then satisfying that need, the institute pushes the other way, finding a place to put whatever products the industry has. The record run of red salmon in Bristol Bay is a perfect example. Heimbigner explains, “We’re working closely with our industry to identify and build markets for different sockeye products forms.”

While sockeye salmon is Alaska’s most valuable fishery, pollock is vastly more voluminous, with more than 3 billion pounds caught each year. Worldwide, Alaska pollock is the most harvested fish, so GAPP is constantly building demand so the catch has a plate to land on.

In 2018, GAPP hired Morris as its CEO based on his experience at the National Pork Board. During his tenure there, the United States became a net exporter of “the other white meat.” No offense to pigs, but now Morris is fully behind what he calls “the perfect protein.”

AFDF

While he works in Seattle, Morris speaks for harvesters and processors located in Alaska, such as the Coastal Villages Region Fund, the Peter Pan Fleet Cooperative, and Alyeska Seafoods in Unalaska. One of the obstacles he must overcome, ironically, is pollock’s ubiquity as the archetypal filet-o-fish.

“We’re overwhelmingly a fish that’s found in the frozen food aisle, battered and breaded. And we’re overwhelmingly a fish that’s found in quick-service restaurants, battered and breaded,” Morris says. “Although those are two really important channels for us, we do want to break out of that, just to make sure our industry can manage risk.”

Pollock was COVID-19-proof, Morris says, because grocery stores and drive-through fast food remained open while restaurant fare shut down. However, he has bigger aspirations for pollock—or rather, as Morris is always careful to say, wild Alaska pollock.

During the campaign, the professional celebrities exhibited meals made mostly with fileted Alaska pollock, whether barbecued, seared, baked, or as ceviche. A couple used surimi fish paste to dress up a Thai salad or ramen noodles.

Each influencer framed the dish with their own perspective. As Morris explains, “If they talk about sustainability, if they talk about nutrition messaging, if they talk about versatility, or if they talk about high-end cuisine—what are those sorts of messages that are resonating the most with the followers?”

GAPP has contracted a public relations firm to analyze how the campaign affected purchase behavior.

My Nguyen

My Nguyen

As far as the rest of the world is concerned, Alaska is a fish basket. Overseas sales of all seafood totaled $1.8 billion in 2020, outpacing all ores. A single subcategory, “frozen fish meat” surpasses all exports except for zinc, lead, gold, and the portion of crude oil that isn’t refined domestically.

Foreigners pump cash into the Alaska economy for seafood that Alaskans might never eat.

“An obvious example is sea cucumber, which is a dive fishery in Southeast Alaska, primarily,” Heimbigner says. “It’s a species that doesn’t often find its way to Alaska menus but is a hugely coveted delicacy in many markets outside of the United States, especially in China and Asia.”

Heimbigner adds that Alaskans might not appreciate the state’s bounty of flatfish, including yellowfin sole, rex sole, rock sole, flathead sole, arrowtooth flounder, and Alaska plaice. “They’re all very versatile lean, nutritious whitefish that are found on menus across the United States but not often seen here at home,” she says. “I think many Alaskans are probably unfamiliar with the product and the fact that it comes from Alaska waters.”

ASMI

ASMI

“When I talked to my family and my kids about switching from pork to wild Alaska pollock, my son was the first to say, ‘Dad, raising hogs isn’t cool, but catching wild Alaska pollock in the Bering Sea is.’”

Craig Morris, CEO, Genuine Alaska Pollock Producers

Pollock is, of course, all too familiar, but Heimbigner says ASMI has been working to make its roe as popular domestically as it is overseas. For example: spiced pollock roe in Japan is known as mentaiko. Morris says, “These spiced roe products that you find in everything from pasta to sushi is an amazing product. It’s not uniquely Japanese, but it’s very much celebrated in Japan.”

Japan is also the top market for surimi blocks, whereas the fish paste is known to Alaskans almost exclusively as imitation crab meat. Throughout East Asia, surimi is a staple ingredient for boiled fish balls, and Morris says Alaska pollock is the ideal raw material. “Wild Alaska pollock surimi comes out of that very cold water that gives that surimi block very high ‘gel strength,’” he explains. “You can put it in that boiling water, which is a very extreme cooking environment, and it doesn’t dissolve like a bullion.”

The problem with selling surimi to Japan is that the market is shrinking. Japan has one of the lowest fertility rates of any country, and its population has been dropping for more than a decade.

“The demographics just aren’t in Japan’s favor,” Morris says, “so if we’re gonna enjoy demand in the future as strong as we enjoy today, we’re gonna have to identify and develop new markets to help pick up the demand.”

Identifying and developing new markets has been the mission of ASMI and AFDF for more than forty years, with no coda in sight.

“It’s a big, wide world out there with a lot of other seafood species, and we are facing a lot of competition,” Heimbigner says. “In order to stay relevant to our customers and consumers around the globe, it takes a lot.” ![]()