USNC

he 20MW reactor at Fort Greely was the state’s first—and, for the time being, only—nuclear energy project. From 1962 to 1972, SM-1A provided steam heat and electricity for Fort Greely. Operating costs were too high, though, so the reactor was shut down.

“The control rods, all the radioactive waste, all the radioactive liquids were sent to the Lower 48, but some of the lower-dose materials were left up there for our future efforts,” says Brenda Barber, program manager for the Environmental and Munitions Design Center at the US Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) Baltimore District.

Fifty years after SM-1A was mothballed, USACE is responsible for final cleanup. “These sites have to be fully decommissioned and dismantled within sixty years of initial shutdown. For Fort Greely, that’s 2032,” Barber explains. “Our clock is ticking.”

Engineers encased the SM-1A containment vessel and reactor components in concrete, which makes the decommissioning unusual. “We’re going to have to remove all that concrete so we can gain access to the reactor components and then remove them. So we do have some added complications at Fort Greely,” says Barber.

Last July, USACE awarded a $103 million contract for the decommissioning to Westinghouse Government Services of South Carolina. For comparison, the construction cost of SM-1A and its prototype, SM-1 at Fort Belvoir in Virginia, was approximately $20 million each, adjusting for sixty years of inflation. Who said it was easier to destroy than create?

To shrink the life-cycle cost of the next generation of nuclear power, a separate division of Westinghouse is working on a new system named eVinci. Whereas SM-1A is stationary and medium-sized (hence the designation), eVinci is mobile and smaller than small; it’s considered “micro,” a 5MW reactor that fits inside a 40-foot shipping container.

Westinghouse Vice President of New Plant Market Development Eddie Saab says eVinci is designed to be removed from a site and leave nothing behind. “We believe we will be able to accomplish that with eVinci by making it transportable,” he says. “There’s more confidence in the back end because of the transportability.”

Instead of monumental edifices, microreactors look more like construction office trailers, and they could be just as temporary.

USNC is a Seattle-based startup that is developing its own microreactor, the Micro Modular Reactor (MMR). The core is buried underground, upright, next to another module that circulates helium coolant. The helium transfers heat to molten salt, which is pumped to a neighboring steam turbine to drive the generator. Molten salt also stores heat overnight to be released during daytime hours.

MMR and eVinci are both designed to be refueled by the manufacturer: reloaded after twenty years in the case of USNC and totally reclaimed and, if desired, replaced after at least eight years in the Westinghouse approach.

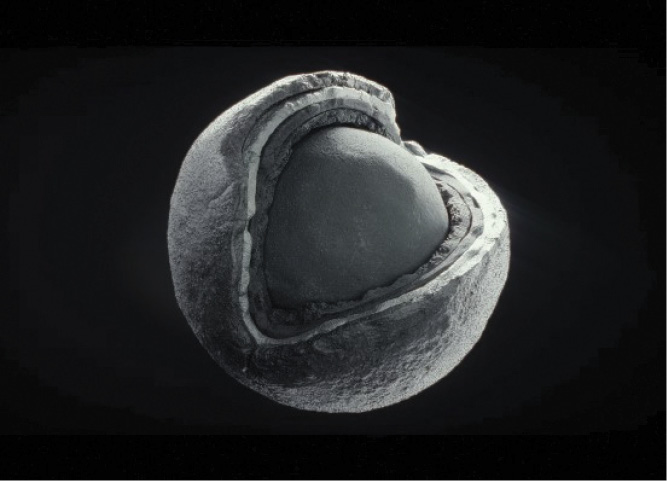

The form of the fuel, called TRISO, makes microreactors possible. Tiny spheres of uranium are coated with ceramic, and the composite grains are packed into pellets. “We think that it’s better to have the fuel safe rather than building a safety system around it,” Rabiti says. TRISO has been around since the ‘60s, but recent breakthroughs allowed for scaled-up manufacturing.

Westinghouse needed another innovation to make eVinci possible: heat pipes fabricated to very precise tolerance. “We quickly recognized that the capacity did not exist in the marketplace. To be able to solve that, we have to do it ourselves,” Saab says. The prototype uses heat pipes that are 4 feet long; earlier this year Westinghouse successfully fabricated 12-foot pipes for the next test unit. The commercial model will likely use 22-foot pipes, assuming they are smooth enough.

Heat pipes are key to the eVinci design. “The air coming in absorbs the heat generated in the heat pipes and goes to a power conversion unit,” Saab explains. “When you pull the heat away from the heat pipes, the sodium goes back to its liquid state from gas and moves back to the other side.” A system driven by simple thermodynamics, with few moving parts, minimizes points of failure in the interest of safety.

USNC has a passive design that relies on high surface area to maximize heat dissipation, which it bills as “walk-away safe,” as bold a promise as the company’s name: Ultra Safe Nuclear Corporation. Confidence, or tempting fate?

“I always say, don’t let engineers name a company,” says Mary Woollen, USNC’s director of stakeholder engagement. “And it’s funny because we’ve had some people that love the name, but mostly it’s just, sort of, there it is.”

“They actually approached us,” says CVEA CEO Travis Million. “What we found with USNC that was really attractive to us is that they were truly looking to partner with somebody and work collaboratively to try to find a way to make this work.”

The Westinghouse and USNC products are both transportable 5MW modules, yet they differ in key respects. For instance, eVinci sits on a concrete pad, which suits Alaska conditions where permafrost is difficult or expensive to excavate.

On the other hand, USNC is using an underground approach. “The main reason is for a design requirement to withstand an airplane crash” or other external hazard, Rabiti says. “We have not yet built one, but from what we’ve discussed [with Alaska construction contractors], it is definitely possible to build the reactor.”

“We have really low rates in the summer,” Million says. “Unfortunately, in the wintertime hydro is not really available. We can get about 20 to 30 percent of our needs with hydro in the winter, but we make up the rest with diesel.”

The CVEA board of directors approved a strategic plan in 2021 to reduce dependence on fossil fuel as backup. “My goal would be to not run it, but ultimately I will never be able to retire my diesel plants,” Million says. “With us being isolated like we are, if our transmission line to Valdez were to go down, I need to have my diesel plant up in the Copper River basin to support our members.”

The feasibility study was completed last October. Million says, “We found that there are locations that’ll work in our service territory where we could site a micromodular reactor. We found the integration into our system would actually work out very well, more or less. We found that social acceptability was pretty good in our service territory.”

However, the economic factors are complicated by the unknown variable of alternative energy grant funding. Furthermore, to make the finances add up, “We would have to sell excess heat in addition to generate electricity because we don’t need electricity all the time. We would just need it in the winter months.”

The reactor’s excess heat could be tapped off for a major customer, such as community heat loops, fish processing, or industrial processes. Until then, “It doesn’t make sense and it’s too risky for our membership to own and operate the facility,” Million says. “But if we can negotiate a power purchase agreement with USNC that benefits our membership, then we may go forward.”

Westinghouse

Eielson was selected in October 2021 to host a pilot project for the Air Force’s first (and so far only) microreactor, replacing the base’s coal-fired power plant. A request for proposals closed January 31, 2023, and the project is now in the source selection phase.

Among the potential sources is Westinghouse. “Our technology is well suited for that application,” says Saab, although he has reservations about the process. “I think the Air Force is going through a first-of-a-kind procurement model; they’ve asked for a power purchase agreement, which for a first-of-a-kind technology can be challenging.” He says Westinghouse provided recommendations to adjust the process, so he hopes for good dialog with the Air Force.

Eielson, Fort Greely, Copper Valley… why is the Richardson Highway Alaska’s nuclear neighborhood? Turns out to have the magic mix of off-the-grid and on-the-road.

“We definitely need a certain amount of people to be sure that we have enough demand for those reactors… That is part of the math,” says Rabiti. “And the other thing in this area, [with] the connectivity to the grid, the price of electricity is high. So essentially, it’s a kind of mix of two components: the price of electricity and the presence of a large enough base of customers.”

Million also sees the region as a sweet spot. “The fact that we’re on the road system to where a unit could be deployed and demonstrated and could be easily accessed, I think, was a big driver as well,” he says. “I think the manufacturers right now are wanting something that they can easily get access to and keep an eye on while they’re deploying and testing.”

Saab concurs. “Typical first deployments are in areas that are accessible and have an immediate need,” he says. “I do anticipate, and I am hopeful that, as eVinci shows success in Alaska, it unlocks additional opportunities across Alaska, and those end-users or communities can benefit from the technology.”

A few months later, Dunleavy signed the bill into law at his first annual Sustainable Energy Conference, where nuclear energy was easily the most common alternative source represented at vendor tables. Westinghouse was there, drumming up interest in eVinci.

“When we look in Alaska, we see remote communities, we see industrial applications where there isn’t an easy connection to the grid to provide that power,” says Saab. Indeed, he says design started with those applications in mind, which led to the 5MW form factor.

Not many off-grid villages need a 5MW power plant, though. Of the fifty-eight communities in the Alaska Village Electric Cooperative, only Bethel uses at least that much power; the rest have generating capacity of 1MW, give or take.

That’s fine, says Saab; eVinci can be throttled down. “The luxury of the technology is the output and the operational life are fairly linear: if there is a need for half the power, for 2.5MW, we can actually run the eVinci for about sixteen years,” he says.

Westinghouse

But why should Alaska import uranium-fueled modules when the state has more wind, hydrokinetic, and geothermal energy than it can use? Saab views microreactors as a bridge to decarbonization, which would include extraction of critical minerals. “If we want to unlock some of the natural resources in certain regions, you need a technology that can do it safely,” he says.

Partly for that reason, Westinghouse was invited to a recent luncheon at the Alaska Support Industry Alliance, a nonprofit mainly interested in oil and gas development. Alliance CEO Rebecca Logan welcomes nuclear energy to the state’s portfolio. “A huge driving interest is that we have less oil and gas work,” she says. “You’re always looking at where the next jobs are coming from and what new things are coming to Alaska.”

USACE Baltimore District

Yet pushback in Alaska has been relatively mild, according to Saab. “When we provide the facts and the science, people are open to listen,” he says, adding that skeptics are mainly waiting to see the technology tested somewhere else.

Million has seen a similar reception from CVEA members. “A lot of the people that were either on the fence or adamantly against it were either more open-minded or accepting of it. There are a few groups of people that are just adamantly against anything nuclear at all, and, you know, it’s just how it’s gonna be,” he says.

“There will be no reactors anywhere unless you can gain public trust,” says Woollen. “We don’t aim to try to change hearts and minds, but I do ask that, I mean, I hope that people can at least listen, try to understand, and then make their judgments.”

Meanwhile, the CVEA board is expected to decide late this summer whether to go down the reactor road. “We’re going to continue to have conversations with our membership and any stakeholders who are interested with our process, and we’ll be working with USNC to see if we can develop a contract that works for them and works for our members,” says Million.

The only nuclear power plant to ever operate in Alaska is being decommissioned at the same time the new generation of microreactors is coming to the state. Is that

a coincidence?

Westinghouse

Yet Barber suggests a way USACE’s work might have contributed to commercial developments. “Likely why you’re seeing what you’re seeing in the microreactor arena is that we were able to demonstrate the life-cycle completion of a reactor,” she says. “When we decommissioned and dismantled the MH-1 on the Sturgis vessel, the Army could demonstrate that full life cycle cost, so it did provide some input into potentially bringing reactors back online.”

Whichever vendor supplies Eielson, and whether CVEA brings nuclear energy to its Richardson Highway grid, the process is a learning opportunity for Alaska as a whole. Million says, “If it doesn’t work for us, but the work that we’ve done on the front end helps benefit another utility to go forward with it, I look at that as a huge win.”