hile the lion’s share of attention on Alaska’s oil and gas industry centers on the North Slope, the Cook Inlet region is still home to twenty-eight producing oil and gas fields on- and offshore.

Between rigs operating in the inlet itself and refineries based in areas like the Kenai Peninsula, Cook Inlet is a crucial—and sometimes overlooked—piece of Alaska’s oil and gas industry.

Gas follows the same pattern. Whereas most of the gas produced during oil extraction on the Slope is reinjected into the ground, Cook Inlet gas is the lifeblood of Southcentral electrification.

According to Kara Moriarty, president and CEO of the Alaska Oil and Gas Association, “Cook Inlet is incredibly important: every drop of oil produced in the inlet goes straight to refineries that are powering our cars, our airplanes, and our boats, especially in Southcentral Alaska. More importantly, the gas production from Cook Inlet is what powers our heat and our lights, and we’re not going to experience the chaos that Texas had in February. We have very reliable gas production right now. It’s very important to Southcentral utilities.”

Tom Walsh, one of the managing partners of Petrochemical Resources of Alaska (PRA), believes that “things are a lot better off since 2009.” When PRA performed its first Cook Inlet gas study, the company estimated there would need to be gas imports to meet Alaska’s energy demand. But that hasn’t been the case.

“There’s been a huge consolidation with Hilcorp being the very dominant force in Cook Inlet,” says Walsh. “They’ve done a great job of revitalizing the Cook Inlet portfolio with offshore and onshore investments and finding gas and oil behind pipe. In drilling new wells, Hilcorp has been extremely successful in getting things back in line where there’s enough supply for Southcentral Alaska now. They really have a great deal of dominance in Cook Inlet. I think the gas is now available there to meet demand.”

With Chugach Electric Association’s acquisition of ML&P and its Beluga field asset, Chugach secured long term gas supply at relatively reasonable costs. Walsh says, “Chugach has more impact now since they’ve taken over two-thirds of the Little River Field, so they’re going to want to try to align their activities with Hilcorp as the operator in the Little River field. However, their interests aren’t exactly in alignment. So that’s going to be a little bit of a challenge to get the gas they want—from the field they want—and not stretch Hilcorp too much. Hilcorp has agreed to supply that gas to Chugach, but it may not be from the field Chugach would like to see further developed.”

Walsh notes that Hilcorp has invested millions of dollars in aging infrastructure both on- and offshore, recently completing a roughly $90 million subsea pipeline project to allow oil produced from West Cook Inlet fields to be piped to the refinery at Nikiski. The project coincided with the closing of the Drift River oil storage terminal, long seen as a potential environmental hazard for its location at the base of Mount Redoubt. Hilcorp has been able to increase production in every platform and every onshore facility that they acquired about ten years ago.

The Kenai liquefied natural gas plant, which has exported natural gas overseas from Nikiski for nearly four decades, got federal approval to start importing natural gas. That could give parent company Marathon Petroleum a more cost-effective way to power its crude oil refinery down the street.

Marathon subsidiary Trans-Foreland Pipeline applied last year to reactivate the historic plant as an import facility. They received the go-ahead in early December 2020 from the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission. With approval in hand, Marathon has eighteen months remaining to act on its proposal. The company has not yet determined its plans for the facilities going forward, but that the project provides an opportunity for the company to get low-cost fuel to the refinery.

Johnson points to an investment opportunity BlueCrest pursued almost a decade ago to illustrate this issue.

“Together, [with] a small group of investors and based upon the promises of the State, we bought the Cosmopolitan field from Pioneer in 2012. At that time nobody really knew what was there. There had never been a well drilled out into the top of the field. Conoco had drilled from onshore back around 2001, and they had discovered oil there, but they couldn’t tell what was there—they did not have good seismic data. Then, Pioneer came in and they were going to develop it and then they pulled out of Alaska. They said, ‘Why should we invest our money in Alaska when we can do it with a better ROI in West Texas.’

“BlueCrest looked at it and saw an opportunity and we drilled the first offshore exploratory well in a couple of decades and we found, frankly, a large field—put it that way.”

Johnson notes the field isn’t nearly as big as those found on the North Slope but that there is still a substantial amount of oil. “So with that, we put in hundreds of millions of dollars to get started on this work, with the expectation that the state would at least abide by their commitment to pay these tax credits to us as they told us that they would.

“Then when the State stopped and said, ‘Nope, we owe you $100 million, but we’re not going to pay it to you,’ our investors said, ‘Well I think I’ll put my money someplace else.’” Luckily, BlueCrest’s partners remained invested, and the company is still in conversations today with other potential investors.

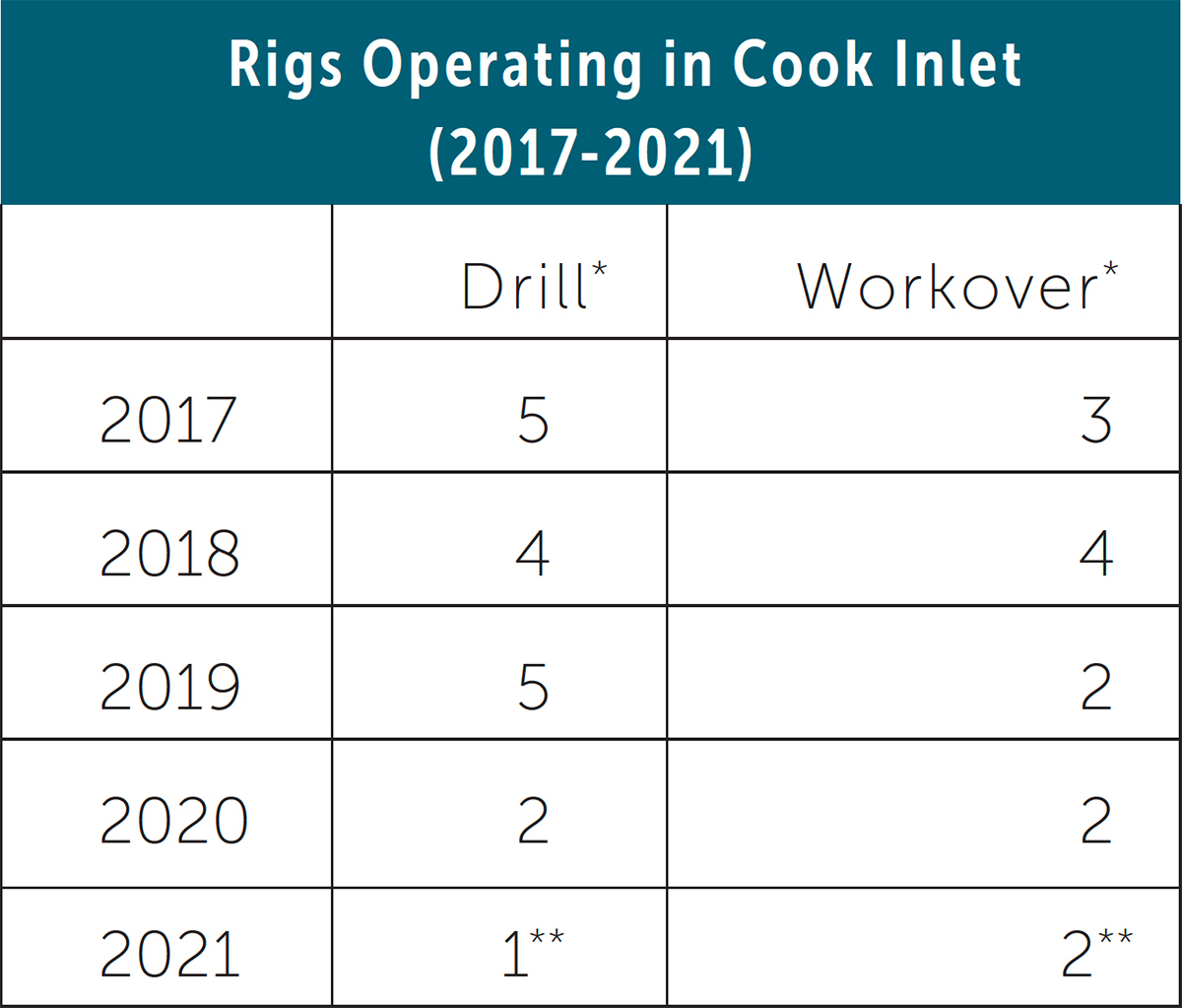

** Through March 31, 2021

With the suspension of oil tax credits, Johnson says there’s a “fear of Alaska” from an investor’s point of view. “We’ve got support currently from the governor of Alaska and the legislators, but people need to understand that just because it’s a good deal doesn’t mean that people will necessarily invest their money.” He notes that BlueCrest’s Cosmopolitan Field is the largest undeveloped gas field in Cook Inlet; the company’s intent is to get that field to production within a couple of years, which will help supply Southcentral’s power needs for the next ten years.

BlueCrest has one of the largest rigs in Cook Inlet, and the company is ready to deploy its extended reach drill with the unique capability of searching multiple layers using “fishbone” technology. “We’ve got the well planned, and the economics would be good, but investors are waiting to see what the environment is going to be,” says Johnson.

What that environment looks like will be heavily impacted by the new presidential administration. Johnson says, in response to the Biden Administration’s stance on environmental protection, “We clearly understand that protecting the environment and climate change is a very important issue for the entire world. It’s not something that’s focused on an individual area. This is a global issue. What has happened is that the Biden administration has said that we are just going to stop producing oil and gas.”

Since assuming the operatorship of the Cook Inlet Kitchen Lights field in July 2020 (after acquiring Furie Operating Alaska), HEX Oil teamed up with Rogue Wave AK in 2020 to form the joint venture Hex Cook Inlet (HEX CI). Since July of 2020, HEX CI has increased the Kitchen Lights Field natural gas production by at least 20 percent.

“Right now, it all goes back to basics,” says HEX Oil CEO John Hendrix. “We’ve been basically going back through the well files and understanding the decisions they have made—right or wrong—while building our own philosophy around how to develop the field. Our work includes making the sure the temperature sensors are going to the right part of the equipment that we think it is and making sure the well files are in good working order.”

As of publication, HEX CI was waiting for the Alaska Department of Environmental Conservation to issue a water handling permit that would allow the company to return the freshwater produced as part of the drilling process back into the inlet, as opposed to piping it to onshore storage. In the meantime, Udelhoven Oilfield System Services is installing water handling equipment on the platform in hopes that it will be ready for production immediately upon receipt of the permit.

Both Hendrix and Johnson agree on one thing: If Alaska wants to ramp up production in Cook Inlet, the state needs to create a more sustainable business environment for attracting investors. Changing the rules mid-game for potential investors creates uncertainty—and having a long-term plan is a must. ![]()