carbon-neutral oil company would have sounded like an oxymoron a few decades ago.

But in the last several months, two major companies announced ambitions to reduce their emissions and take steps to cancel out the effects of their remaining carbon footprint. They say their pledge applies to both emissions from producing fossil fuels and the emissions produced when consumers burn it.

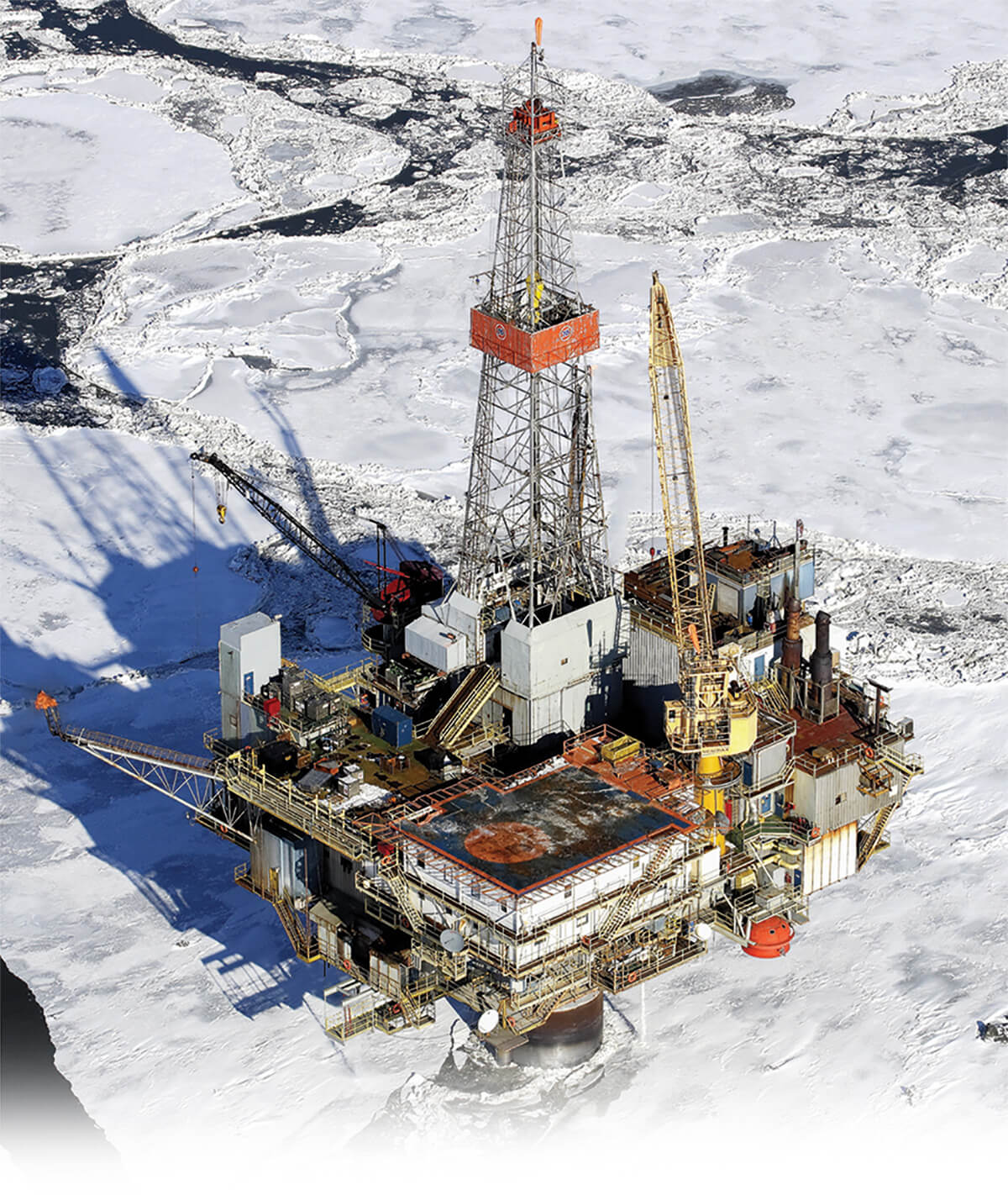

First came Repsol, a Spanish oil company that owns dozens of North Slope exploration blocks and reported the Horseshoe well discovery near Nuiqsut in 2017. Repsol announced its net-zero carbon plans in December.

carbon-neutral oil company would have sounded like an oxymoron a few decades ago.

But in the last several months, two major companies announced ambitions to reduce their emissions and take steps to cancel out the effects of their remaining carbon footprint. They say their pledge applies to both emissions from producing fossil fuels and the emissions produced when consumers burn it.

First came Repsol, a Spanish oil company that owns dozens of North Slope exploration blocks and reported the Horseshoe well discovery near Nuiqsut in 2017. Repsol announced its net-zero carbon plans in December.

The companies don’t plan to stop producing oil, even by their 2050 deadline to become carbon neutral: they do, however, plan to focus on cleaner fuel sources.

A lot has changed in the last decade or so, at least in terms of corporate stance on the issue. Today most of the world’s major oil companies acknowledge the existence of climate change and the role in it that oil and gas plays.

The OGCI announced new carbon capture and carbon-intensity goals last September at its annual meeting on the sidelines of the United Nations Climate Summit in New York.

OGCI

Half of staying within a carbon dioxide budget means finding ways to emit less. The other part of the balance sheet is finding ways to remove greenhouse gasses from the atmosphere.

Growing more trees is one way to take carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere and store it. But there are also mechanical ways: one method, carbon capture and storage, separates carbon dioxide from other gasses in power plant and factory smokestacks. The carbon dioxide is then injected deep underground so it doesn’t enter the atmosphere and contribute to climate change. Another approach is carbon capture and use, where the extra carbon dioxide is used to make products from plastic to biofuel.

Unfortunately for Alaska, carbon capture projects tend to get funded mostly in locations with a greater density of emission sources because there are better economies of scale. The OGCI is investing in five carbon capture hub projects this year. The only US project is along the Gulf of Mexico near Houston, a site chosen to take advantage of a cluster of power plants and factories.

But there has been research into carbon capture in Alaska. In 2013, a 200-page University of Alaska and Department of Defense study evaluated storing carbon dioxide from an Eielson Air Force Base power plant in underground coal seams or oil wells; however, the Eielson power plant was never built.

US Senator Lisa Murkowski, who chairs the Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee, sees a place for carbon capture at Alaska’s coal and natural gas power plants, as well as on the North Slope, says Grace Jang, a spokeswoman for the committee.

These upstream carbon emissions are a significant part of the total carbon footprint. On average, about a fifth of the complete “well to wheel” carbon cost of oil comes from these costs, says Julien Perez, the vice president of strategy and policy at OGCI.

The amount of carbon needed to produce oil or gas is known as its carbon intensity. Carbon intensity can vary widely between producers.

In 2017, OGCI members produced oil and gas with an average carbon intensity of 24 kilograms of carbon-dioxide-equivalent-gas per barrel of oil energy, according to the organization’s annual report. The OGCI also reported that this baseline number was less than half the industry-wide carbon-intensity average.

The OGCI companies are already ahead of the industry in reducing emissions because they got a head start, says Perez. Large oil and gas companies have been working to reduce their carbon intensities for decades and are now collaborating.

“The collective actions we conduct through OGCI, to share best practices and incentivize their implementation, allow [them] to further reduce their footprint,” he says.

Why did BP make the move? A few different narratives have emerged. One is a traditional return on investment explanation. In a September conference call organized by JPMorgan Chase, BP’s then-CEO Bob Dudley said that BP wanted to prioritize other developments that have more growth potential.

“We are certain we’ve got a path, it may not be linear, to being consistent with Paris goals,” Dudley said in the call, as reported by Bloomberg News. “There are going to be projects that we don’t do, things that we might have done in the past. Certain kinds of oil, for example, that has a different carbon footprint.”

Asked about the role of Alaska in BP’s climate initiatives, BP Alaska spokeswoman Megan Baldino declined to comment, referring questions to BP’s website.

“It’s not our story to tell any more,” she says.

troutnut | iStockphoto

troutnut | iStockphoto

Flaring is the combustion of natural gas at an oil well. Flaring gas doesn’t produce usable energy but can be necessary to relieve pressure and prevent a well blowout. In some places, oil producers flare gas for long periods of time when there is no infrastructure to bring the gas to market.

In 2018, 1.85 percent of natural gas taken from the ground in the United States was lost to either flaring gas or venting it, according to the US Energy Information Administration. Flaring was especially notable in North Dakota that year, where 17 percent of natural gas withdrawals were flared.

Alaska has a particularly low rate of flaring. Last year, the rate was 0.3 percent says Dave Roby, a senior petroleum engineer at the Alaska Oil & Gas Conservation Commission (AOGCC).

“Over the past decade it’s bounced between 0.2 and 0.5 percent,” he says. “It’s been below 1 percent for quite a long time.”

Alaska’s laws keep the amount of gas lost to flaring and venting down. With only a few exceptions, producers need to get approval from the AOGCC before flaring.

Strict flaring rules date back to the discovery of oil at Prudhoe Bay. To protect the state’s share of oil revenue, the state legislature created the AOGCC, a quasi-judicial body empowered to enforce regulations that prohibit the waste of oil and gas.

As oil and gas companies continue to work on lowering their carbon intensity, flaring is an obvious target. Flaring is a significant source of emissions and, unlike many other sources of emissions in the supply chain, is visible and already monitored. ![]()