or nearly four decades, there have been conversations about upgrading the Sterling Highway between Sunrise Inn and the eastern entrance to Skilak Lake Road near Cooper Landing. Those upgrades are now underway as a part of the Department of Transportation and Public Facilities (DOT&PF) Sterling Highway MP 45-60 project, a development with an estimated cost of $375 million and a projected completion date of 2025. “It’s hard to pin down the actual date, but I’ve heard 1982, or even maybe before, is when the first go at this environmental impact study started,” says DOT&PF Project Manager Sean Holland. “We were finally able to get a record of decision in May 2018 that’s letting us move forward with the Juneau Creek Alternative.”

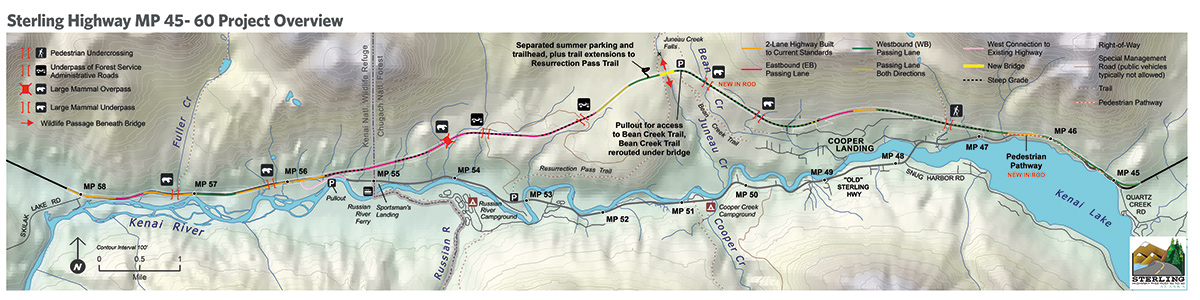

DOT&PF considered five alternatives—four build alternatives and a No Build option. In the end, the Juneau Creek Alternative was chosen and will include a new alignment section that will start at MP 46.2 and end at MP 56. A part of the project’s new alignment section will be the construction of the Juneau Creek Bridge, which as planned will be the longest single-span bridge in Alaska.

“It’s going to be a bridge that, depending on geology, will have a clear span of 450 to 825 feet,” says Holland.

In order to meet current highway design standards, Holland and DOT&PF are focused on creating 12-foot-wide lanes and 8-foot-wide shoulders. “The highway is classified as a rural highway—there are no shoulders there,” says Holland. “A rural highway has a minimum of a 6-foot shoulder and preferably an 8-foot shoulder. Fifty percent of the curves during that stretch, from [mile post] 45 to 60, are too sharp. They don’t meet current design standards.”

The first design phase focuses on the east and west ends of the highway that will lead to the new alignment. HDR is contracted to provide environmental and public involvement support while designing the west end, MP 56-58. Working as a subcontractor to HDR is R&M Consultants, which is tasked with the design of the east end, MP 45-47. “HDR has the longest history with the project and they have the most knowledge,” Holland says.

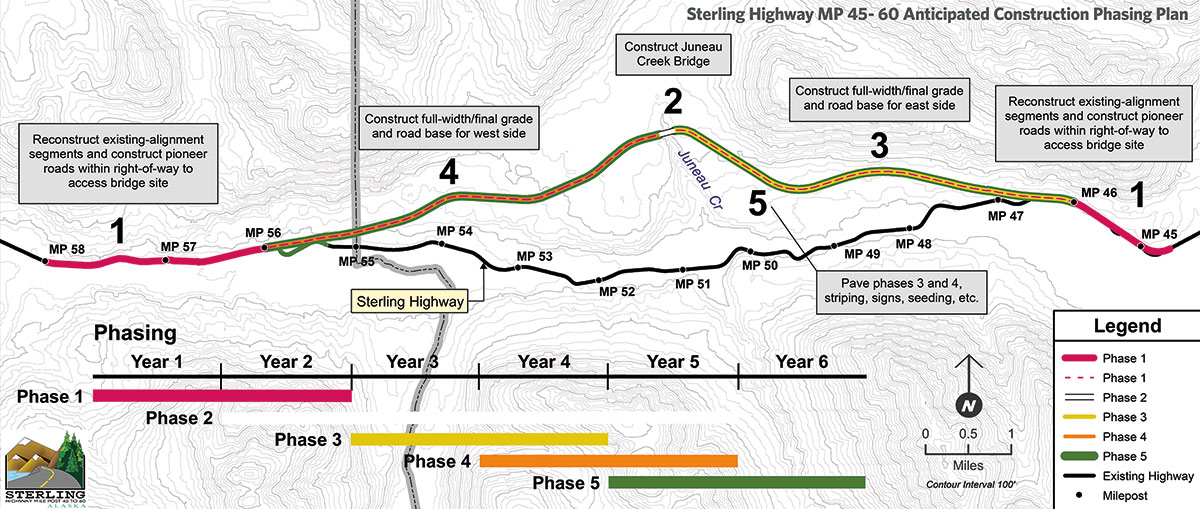

Holland notes the west end is classified as Phase 1A, which will comprise the reconstruction of the existing alignment segments and construction of pioneer roads within right-of-way to access th.e bridge site. The same work will be done on the east end (Phase 1B). Phase 1A design is expected to be completed this fall, with the design of Phase 1B anticipated to be completed in early 2021. Construction on the two ends is slated to begin during the summer/fall of 2021 and take and take one-and-a-half construction seasons to complete.

Part of what makes the bridge complicated is that it travels over Juneau Creek Canyon, in which no work can take place. “We can’t even have temporary work inside the canyon to minimize the impact of the wildlife that travels through there,” Holland says. “There’s a lot of challenges with the entire project, but a lot of it is work that we do every single day. The bridge that we’re building is really uncommon for us.”

The project is expected to be complete in 2025.

“One of them being the schedule: we want to have the contractor on board during pre-construction during our design phases so they can help us come up with a more cost-effective design,” says Holland. “Then we’ll try to negotiate that work with the contractor that we have onboard during pre-construction. Using our traditional method of design/bid/build, we probably wouldn’t be able to meet our build-out schedule of 2025.”

Although Holland notes that, at the time of publication, the contract with Kiewit isn’t complete—“We’ve issued our intent to negotiate and we’re hopeful that we can sign a contract soon,” he says—he remains enthusiastic about the help Kiewit will bring once it joins the project. “If we have the contractor that’s going to do the work onboard, it streamlines a lot of things,” says Holland. “It streamlines permitting, communication with the public. Another thing we’ll be able to do is identify pieces of the work that we can go in and start on early. We might be able to go through and identify what foundations we’re going to need for the bridge so that we can get started on the foundation and not have to wait until we have the design.”

Among the project’s most pressing matters is a clearing contract Holland says DOT&PF will begin advertising in the first quarter of 2020. “We’re going to try advertising for a clearing contract that will clear a 200-foot path through the off-alignment piece and allow us to get up to the bridge and start getting information about the geology up there,” says Holland. “That way we can choose the bridge type and start designing it.” He also notes that Phase 1A probably won’t be ready for bid until August 2020, with Phase 1B being on a similar track, though it could be a little slower because there is property that still needs to be purchased and utilities that need to be relocated.

Holland says he feels fortunate to serve as the project manager and appreciates the impact HDR and DOWL are bringing to the project. “I feel lucky to have this opportunity,” he says. “A lot of people go through their whole career and don’t get to build a project like this. My favorite part of it is being able to involve the whole community, all those consultants and the department, too. Some of the positives about being able to hire an HDR or DOWL is that they have resources down in the states that we can tap into, people that have done work like this in other parts of the country. We have that knowledge that we can tap into, but I like the fact that we’re all Alaskans trying to build everything together.” ![]()