ver wondered why certain careers are called professions? The term comes from the Latin root “profiteri,” as in professing something of importance to others. The hallmarks of today’s professions are years of dedicated training, academic rigor, and a passion for having a positive impact in the community. The first step toward becoming such a practitioner is a professional degree, sometimes referred to as “first” degrees. Theology (MDiv, MHL, BD, or Ordination) and Medicine (MD) were the traditional professional fields, and now the list includes Law (LLB, JD) as well. The medical profession has expanded into Dentistry (DDS or DMD), Optometry (OD), Osteopathic Medicine (DO), Pharmacy (PharmD), Podiatry (DPM, DP, PodD), Veterinary Medicine (DVM), and most recently Psychologists (PsyD, PhD Clinical Psychology).

Like academic PhDs, these are terminal degrees, signifying the highest level of expertise in a chosen field, but usually without a dissertation. The Council for Higher Education Accreditation characterizes first degree programs with the following criteria: 1) completion of the program is required to begin practice in the field, 2) at least two years of college work is required prior to entering the program, and 3) a total of at least six academic years of college work is needed to complete the degree program. Additionally, many professional degrees end with comprehensive exams in order to be licensed, like the United States Medical Licensing Examination, the Multistate Bar Examination, the North American Veterinary Licensing Examination, North American Pharmacy Licensing Exam, or the National Examination for Professional Practice in Psychology.

Every doctor and lawyer in Alaska had to choose to bring their skills back into the state after finishing their education elsewhere. Although there are no medical or law schools locally, aspiring professionals do have a variety of entry points to those career pathways. Undergrads also have many options for completing their terminal degrees.

Alaska is the only state without a law school, so every lawyer is imported. Alaskans who wish to earn a JD must leave the state to attend an accredited law school. According to Alaska Bar data from the last fifteen years, the ten most attended law schools, in order of highest number of active members, are the following: Seattle University School of Law, Lewis and Clark Law School, University of Washington School of Law, Vermont Law and Graduate School, University of Oregon School of Law, Willamette University College of Law, Gonzaga University School of Law, University of Michigan Law School, University of Minnesota Law School, and University of Montana Blewett School of Law.

A new development is on the horizon with Alaska Pacific University (APU) launching an MBA/JD dual degree program this year, which is an accelerated path for both of those graduate degrees. In this new program, MBA instruction is first provided by APU and then JD instruction is provided by Seattle University School of Law through flexible part-time hybrid-online delivery with low residency requirements.

Alaska’s version of a medical school, WWAMI, started in 1971 when the state entered into a cooperative agreement with the University of Washington School of Medicine; the states of Washington, Wyoming, Montana, and Idaho joined, forming WWAMI, the acronym for each of the five partner states. This competitive program, now housed at UAA, provides Alaska students admission to the University of Washington School of Medicine with in-state tuition, which is partially subsidized by the state. In 2021 that totaled more than $3.1 million to support sixty aspiring physicians in years two through four of the program.

Alaska WWAMI students can complete their entire medical education—four years of medical school and three years of residency—in Alaska, with the exception of twelve weeks of clinical rotations in Seattle. WWAMI students spend the first eighteen months of medical school at UAA, taught by more than thirty MD and PhD faculty, and then clinical training during third and fourth years can also be completed in Alaska or Washington before heading out to residency.

WWAMI students have the opportunity to secure an in-state family medicine residency or one of the many specialty residencies out of state, which is important because Alaska needs all kinds of doctors. More than 500 Alaskans have earned their MD through WWAMI, a 97 percent completion rate. The program meets 20 percent of Alaska’s annual new demand for physicians, which is roughly sixty new doctors each year.

Shannon Uffernbeck, the pre-med advisor for the WWAMI program, sums it up well: “WWAMI is dedicated to preparing Alaskan physicians [who] want to come back and serve their Alaskan community.” The success and need for WWAMI is evident in its recent expansion from twenty first-year applicant spots to thirty in the next class.

UAF

The first three years of the program focus on foundational skills, disease-state management, pharmacology, and medicinal chemistry, and the final year is full-time Advanced Pharmacy Practice Experiences at various clerkship sites including in Pocatello, Boise, Coeur d’Alene, Reno, or Anchorage. Alaska’s pharmacists can be found in community settings, hospitals and clinics, academia, manufacturing, as well as the growing field of virtual and remote care.

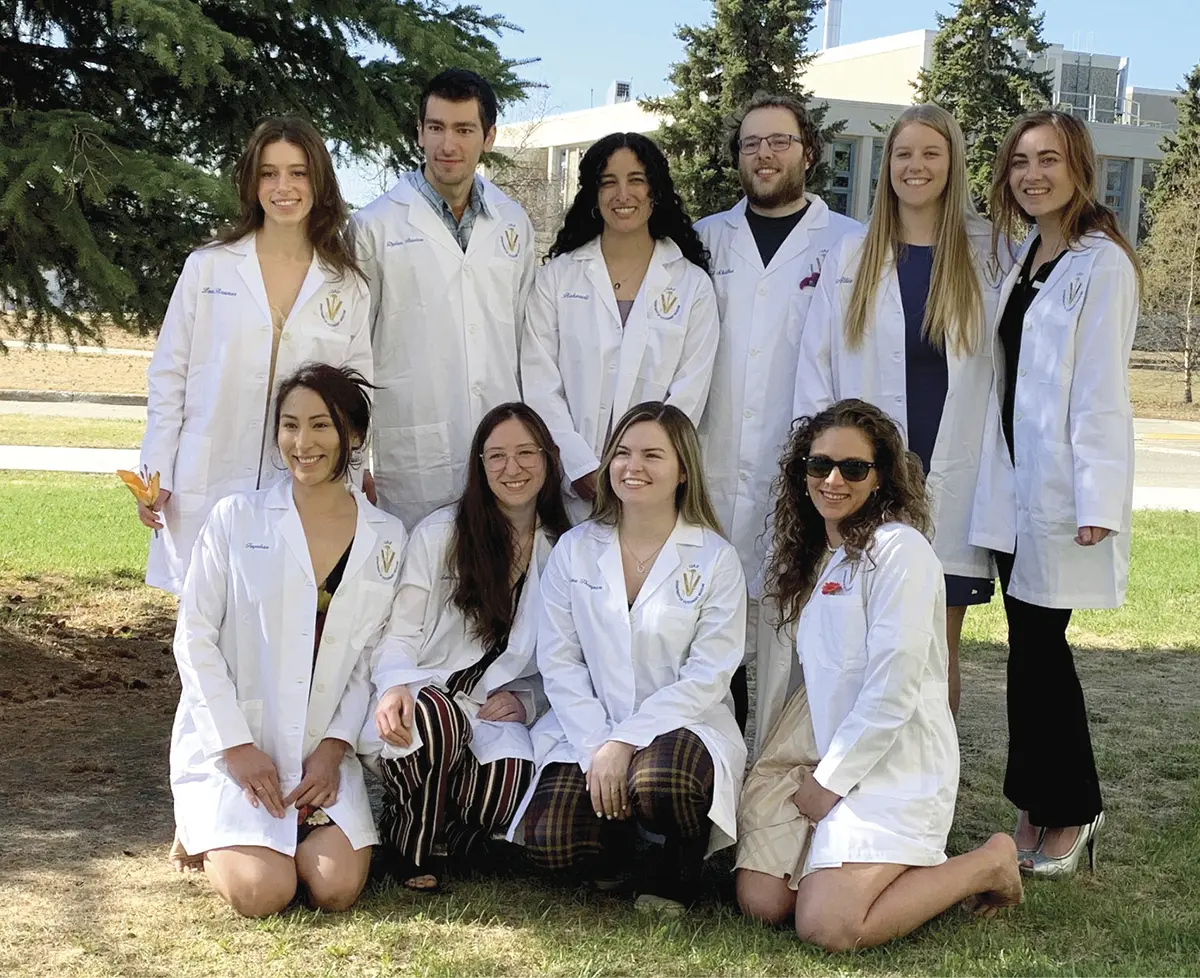

However, veterinary medicine education is available through a 2+2 partnership between UAF and Colorado State University. In this program, Alaska’s future veterinarians attend their first two years of school in Fairbanks then move to Fort Collins, Colorado for their third and fourth years and have their DVM conferred by Colorado State University’s College of Veterinary Medicine and Biomedical Sciences.

“Alaska has significant need for veterinarians in large and farm-animal agriculture as well as wildlife,” says UAF Assistant Professor of Veterinary Physiology Cristina Hansen. “From reindeer to sled dogs, our students get hands-on experience right away during their first semester.”

UAF

Alaska ranks quite high in terms of the number of employed DVMs on a per capita basis, with 32.9 per 100,000, according to a 2024 study by veterinarians.com, placing Alaska as 11th in the United States. That doesn’t illustrate the whole picture, however, as there are many types of veterinarians besides those that serve small animals. Specialties can range from toxicology and surgery to ophthalmology, dermatology, and animal sports medicine. According to the US Department of Agriculture, there remain critical shortages in Alaska for certain types of veterinary medicine, including those that serve beef and dairy cattle, poultry, small ruminant, swine, and equine. The demand for Alaska veterinarians may increase appreciably in the next five years with mass retirements predicted, bigger salaries in Lower 48 states drawing away talent, and the long lead time needed to develop each fully-trained vet.

Professionals can be licensed in Alaska as either a psychologist, which requires a doctoral degree, or as a psychological associate, which requires a master’s degree in psychology. Aspiring psychologist professionals may choose between a Doctor of Psychology (PsyD) or a PhD in Clinical Psychology. Both doctoral degrees qualify graduates to apply for licensure and work with patients, but their focus areas differ somewhat. A PsyD prioritizes practical skills and emphasizes diagnosis, therapy techniques, and working with diverse clients—preparing graduates for hands-on patient care backed by research. A PhD in Clinical Psychology has an additional emphasis in research, exploring the science of mental health, and contributing to new treatments—ideal for those passionate about research and therapeutic innovation.

There are two doctoral programs in Alaska, one at UAA and the other at APU. UAA’s program is a five-year PhD in Clinical-Community Psychology, which includes a master’s degree along the way, with emphasis on research, evaluation, prevention, clinical practice, community, and social action, especially in rural, Indigenous communities. APU’s PsyD program is four years of course work and one year of supervised internship; it similarly includes a master’s degree along the way, though the program is also open to other masters-level professionals. The unique training model of the APU PsyD program, where students meet in-person for several days of intensive instruction approximately every six weeks during the semester, can serve students even in the most remote areas of the state.

Services that mental health professionals provide are important, and the need in Alaska cannot be overstated. The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention identifies Alaska as having the third highest percentage of death by suicide in adults, and the highest for youth and young adults, according to Alaska Bureau of Vital Records. According to the National Alliance on Mental Illness, Alaskans struggle to get the help they need, with 43.1 percent of Alaska adults reporting symptoms of anxiety or depression and 26.5 percent stating they were unable to get the counseling or therapy they needed. There are currently 300 licensed psychologists and 23 psychological associates in the state.

Studies indicate the top reasons why individuals might choose to leave their community are 1) difficulty preparing for careers, 2) social injustice, and 3) inadequate employment compensation, with access to career preparation being the most important factor. Some economists have argued that Alaska has more of a brain exchange than a drain, with individuals from other areas moving to the state to fill professional positions, yet Alaska thrives when it has a homegrown workforce. Local professionals bring a unique perspective and a commitment to staying, contributing to a future filled with innovative solutions for the state’s challenges.

Without a robust pipeline of talented professionals equipped with advanced education beyond the bachelor’s degree and prepared with specialized knowledge and skills, Alaska’s economic progress may stagnate. Investing in future professionals’ education is therefore an investment in Alaska.