n one side of the valley north of Skagway, the Klondike Highway follows the Skagway River, climbs to the 2,865-foot summit between British Columbia and Alaska, and then drops down in flowing curves around scenic mountain lakes and majestic peaks. The road passes Carcross, Bennett Lake, and the headwaters of the Yukon River on its way to the Alaska Highway a few miles east of Whitehorse, Yukon. Further west, the highway continues north to Dawson City, the historic gold rush town on the Yukon River.

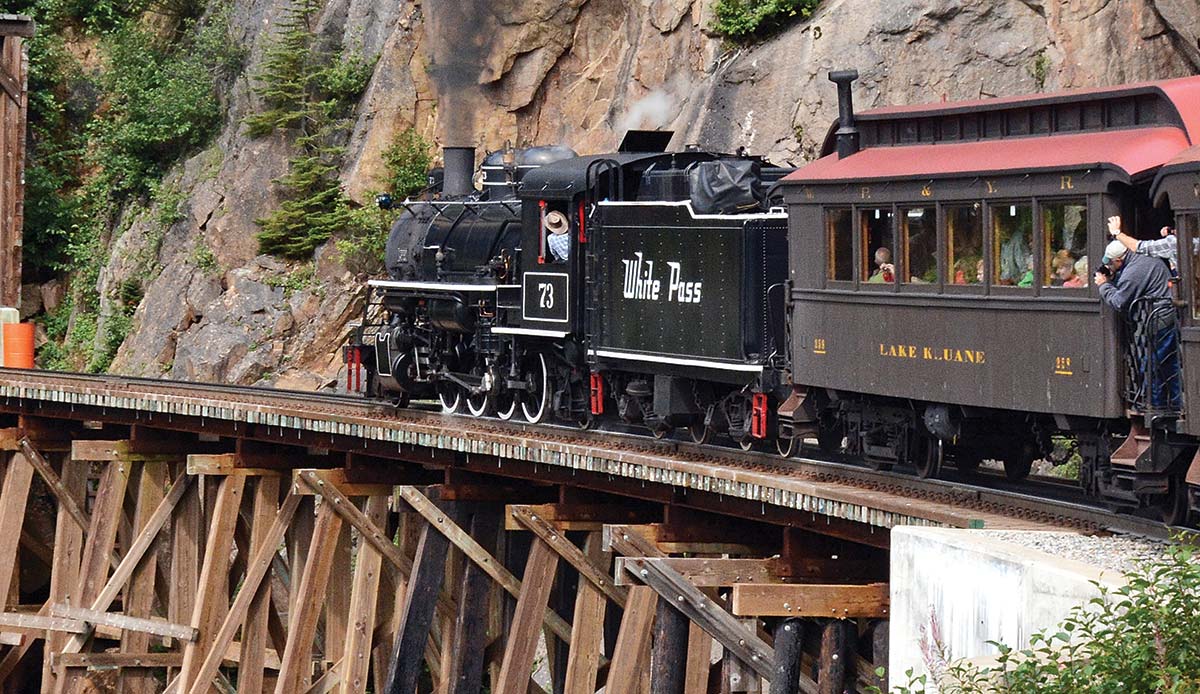

On the other side of the valley, a winding train track cuts into dangerously steep mountain sides, sometimes disappearing around a bend or through a tunnel before meeting up with the Klondike Highway in Fraser, British Columbia. Intimidating peaks tower above the area, some exceeding 7,000 feet in a valley just miles from sea level. These tracks started their journey in 1898, the peak of the Klondike Gold Rush.

Thousands of gold seekers climbed the treacherous Chilkoot trail, making multiple trips with the required one ton of gear. Captain William Moore, a founder of the new city of Skagway on Chilkoot Tlingit land, and First Nation guide Keish (Skookum Jim Mason) believed there was an easier route north. They made the arduous trek to Bennett Lake over what is now White Pass, named for the Canadian Minister of the Interior, Sir Thomas White.

Both the Chilkoot and White Pass trails were plagued with injury, hardships, and death, yet folks with dreams of gold kept coming. In this constant stream of people, two ambitious men saw an opportunity.

Michael J. Heney, a railroad contractor, met Sir Thomas Tancrede in Skagway. Tancrede represented London investors. Money, experience, and vision led to the formation of White Pass Railroad. In May 1898, work on the railroad to Whitehorse began, and construction crews from the north and south met in Carcross in July 1900. By that point, the venture had been acquired by London-based White Pass & Yukon Railway Company (WPY). A golden spike marked the completion of the railroad, which employed more than 35,000 workers during its construction.

In 2018, WPY was purchased by Klondike Holdings, an ownership group formed of majority partner Survey Point Holdings, its affiliates and longtime partners based in Seattle, and Carnival Corporation (parent company of Holland America-Princess) as a minority partner.

About ninety-five parlor cars, forty seats each, wait in the White Pass rail yard. Named after lakes, the cars came from various railroads. The Emerald Lake, built in 1883, is the oldest car. During peak season, all of the cars are utilized. Most have been refurbished or repaired to maintain the vintage decor.

Robert May

Leigh Armstrong | The Skagway News

Mark Taylor, superintendent of rail operations, told The Skagway News. in 2020 that the locomotives, with 3,300 horsepower, can pull more weight, thus saving fuel costs by using fewer engines per train.

The bridges connecting the mountainsides resemble the original crossings, but they have been rebuilt over the years. WPY has its own rail and bridge inspection routine beyond the federal requirements. When updating a bridge, attempts are made to aesthetically match the intricate structures of joists and timbers used in the historic construction. In a few cases, reconstruction includes more aggressive safety designs with retaining walls.

All of their children, and

all of their names

“King of the Road”

“Willi Scheffler, our Canadian roadmaster, has worked with us for over sixty years. He worked with my grandpa, he worked with my dad, worked with me, my brother. I am not unique in that way at all. We have many multi-generational families,” Rose says.

Rose shares the names of a dozen Skagwegians with generations of White Pass history.

“Interwoven families like Mahle, Tronrud, and Hunz, who’ve worked here for generations; and people like Brad Thoe, the longtime spike driving champion and 47-year operator,” he says.

“We have families that stretch back working here for almost over 100 years for some,” Rose says, referring to Carl Mulvihill’s family. Mulvihill’s dad was the chief dispatcher, and Carl worked briefly with White Pass.

Jacqui Taylor-Rose, WPY manager of marketing and product development, and her cousins and family have been working with WPY for generations. Taylor-Rose’s grandfather, Marvin Taylor, was president of the railroad; their uncle was also a president. Taylor-Rose is married to Rose.

“The Lawson brothers work here. Lars is the car shop foreman. Reid is a carman. Their dad, Grant, and their grandfather, Malcolm Lawson, both worked here. The list really does go on and on and on when you get into it,” Rose says.

At the time, WPY managed the Port of Skagway. In addition to rail crew, WPY employed dock workers, passenger expediters, and others. During the off season, WPY supported about 25 year-round employees. When the tourists come to town, the staffing jumped to more than 125 local and seasonal workers.

In March 2020, the town of Skagway felt the winds of a faraway virus. The municipality held a town hall meeting to caution businesses and residents that there was a chance the cruise ships wouldn’t show up, and if they did, traffic might be minimal. The mayor advised businesses to warn their out-of-town seasonal workers to stay put and not come to Skagway. This pandemic was looking to be worldwide.

Line by line, cruise companies sent notice that they were taking ships out of operation. The town of about 800, which depends mostly on tourism and cruise passengers, saw the harbinger of a season dead in the water.

“In the early pandemic, we were still very hopeful that we’d be able to run. But as time wore on, we realized that, you know, without the customer base to come in and support our enterprise, we weren’t going to be able to open,” Rose says.

“We were trying to, for lack of a better term, hold on for as long as we could to the hope of operating our business, like so many businesses. It was very, very challenging for us; financially, emotionally. I mean, it’s a really tough thing,” Rose adds.

On March 21, 2020, the border between Canada and the United States was closed. There would be no individual travelers. WPY parked the trains.

“It was devastating,” says Rose. “I think when you go to zero revenue for that type of period of time—particularly with a railroad, which is a very capital intensive business, in and of itself—and to not have the revenue and be able to support that and still have obligations as far as safety and the maintenance of infrastructure, because you know, you’re going to reopen.”

For the first time since 1982, when metals prices dropped, closing mines to the north, the railroad did not run.

In summer 2022 a series of rockslides occurred on the cliffs above the railroad dock. The forward berth of the railroad dock was closed, and Skagway immediately lost 25 percent of its cruise traffic as ships diverted to other ports.

Experts were brought in; WPY and the municipality met frequently. The slide area has been graded, and large attenuators and sheets of webbing form a defensive block against future rockslides. Cruise lines have examined the slide area and plan to dock in Skagway this season.

In March 2023 the fifty-five-year contract for port operations between Pacific and Arctic Railway and Navigation Company and Skagway ended. WPY still operates the railroad dock, but the overall port is now under direct municipal control.

Residents, businesses, and the municipality are watching the cruise schedules. On one pre-season day, Skagway residents were abuzz about one ship that decided to skip the port. Every ship counts when you’ve had a rough few years.

“The tourism industry, specifically the cruise industry, is the lifeblood of the community. It’s what we do. Having that dock open and available to receive the larger ships and receive our passengers in a safe and effective manner is critically important to the economy in the community,” Rose says.

“Right now we’re working very hard to get as many ships as we can in and move our guests quickly and safely so they can have a great experience in Skagway.”