sk any three architects to define culturally responsive design, and you’ll get four different answers,” Architects Alaska principal architect Stephen Henri says with a laugh.

What is Henri’s answer? “I believe that, as architects, our main purpose for existing is to create places for people, and the way we do that best is if the places we create reflect the people who will be using it,” he says. “To my mind, that means including references to their culture, how they live, and how they think of themselves.”

Culturally responsive design can be expressed in materials, colors, and graphics. Henri adds that it can also be imbued into the bones of the building itself.

“While we do design buildings that are simply functional, when we can, we want a building to be representative of or aligned with the way of life of the people that use it,” he says. “Part of that is more than skin-deep references. It can be part of the actual structure of the building and how it lays out in three dimensions.”

While many buildings throughout Alaska showcase culturally responsive design—most notably, that of indigenous cultures—there are many other examples, in schools, libraries, police stations, healthcare facilities, and more.

“You can’t just come in and create a culturally responsive design. You need to listen to people and be responsive to what they feel is important,” explains Giovanna Gambardella, buildings principal and architectural leader at Stantec. “You’re creating a partnership between the designers, who are experts in the technical aspect, and the community, who are sharing their stories about what their culture means to them.”

Stantec

“You need to ensure that the right cultural bearers are willing to participate,” says Karen Zaccaro, Stantec senior architect. “We don’t want to operate in a vacuum—we need their help to determine what the most important cultural values are to their community.”

To this end, Stantec’s prework procedure includes visioning sessions that define not only who the main stakeholders are but also allow designers to hear from many different people in the community.

“Any community group, like a community council in Anchorage, for example, has a goal or vision they’re trying to reach, but oftentimes they don’t have the same goals,” Nagata says. “During the prework phase, we make sure that everyone is on the same page and is going the same direction.”

Consensus can take time, though. “Not only do you need to get everyone together in a room to listen to each other, but you have to be aware of cultural differences in the way we communicate and in the way that decisions are made,” says Nagata. “You also have to be aware that some members of the group may want a lot of design, where others want it under the radar. Our design process needs to reflect all of these concerns.”

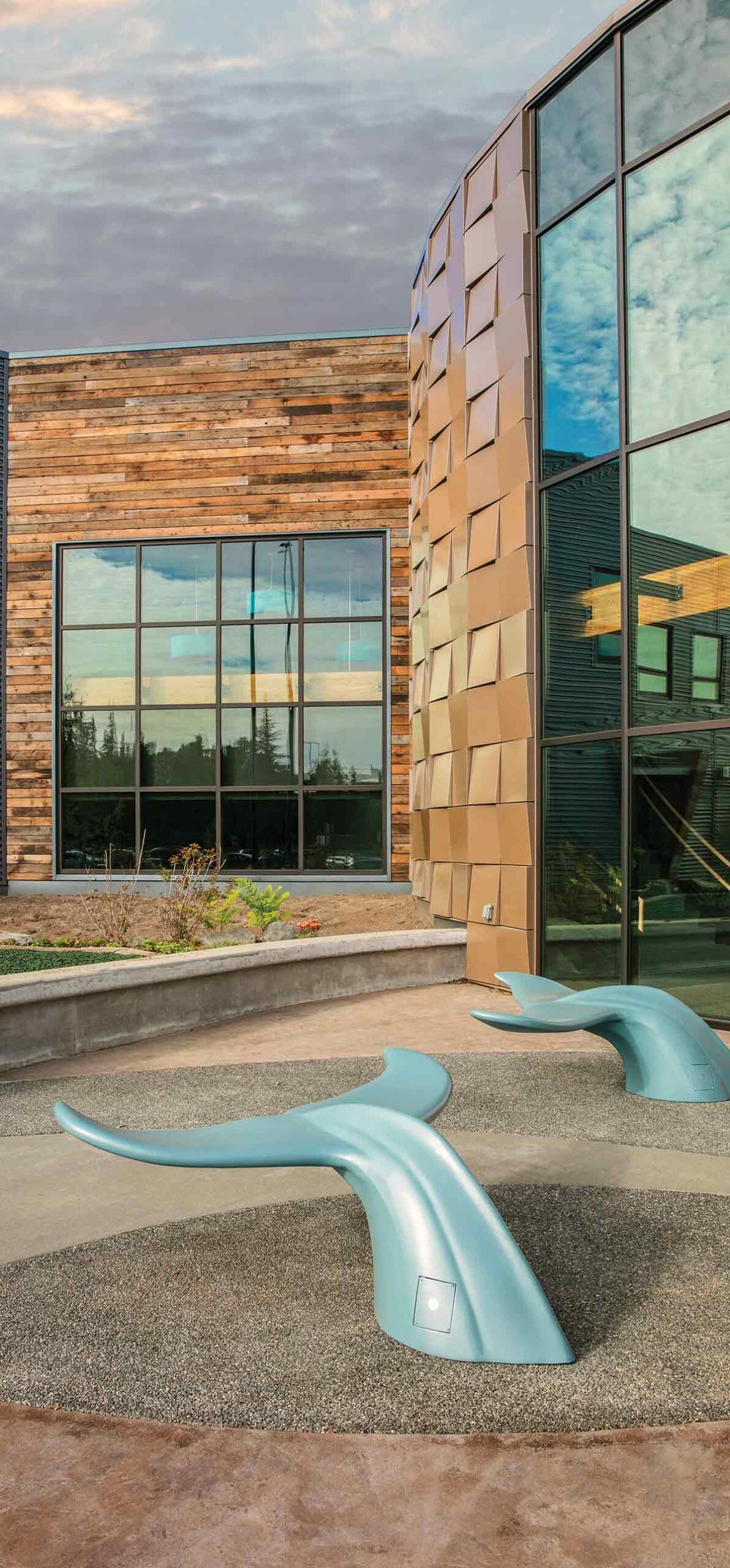

Stantec also worked with the Kenaitze Indian Tribe Education Council on the Kahtnuht’ana Duhdeldiht (Kenai River People’s Learning Place) campus, which opened in 2022. The 67,000-square-foot facility repurposes wood from the community’s historic cannery, and the exterior of the building features a custom copper-colored aluminum panel pattern that simulates salmon skin. The lobby features a 16-foot diameter tribal seal embedded in the floor.

“The council felt that it was important for future generations to explore and learn about Dena’ina culture and that facets of the design could be used as teaching moments,” says Gambardella, noting the 20-foot diameter rendering of the tribe’s Traditional Values Wheel that is displayed on the floor of the multipurpose room. “It’s a very approachable teaching tool that is used every single day.”

Because the tribe historically used three volcanoes in the area as navigation tools, the grain of the faux-wood vinyl floor orients toward those peaks.

“It was really important to that group to have elements that were very personal to their immediate surroundings,” says Nagata. “For example, they have words for every section of the Kenai River, which we used as classroom names. The river also has many different shades of blue, which we used on the building walls and at each of the classroom entries.”

Stantec

Stantec

“The community wanted a welcoming, beautiful space,” says Gambardella. “This wasn’t done as an afterthought; art was integrated into the facility both as part of the façade and the landscape.”

“Whenever we can, we like to include someone on our team as the culture bearer; someone who is either from that local culture or very familiar with it,” says Henri. The culture bearer makes introductions to stakeholders and sets up conversations with people in the community.

For example, while working on Chugachmiut Health Center in Seward, Architects Alaska held meetings with tribal elders who shared the history of a tuberculosis treatment center that had once been on the site.

“A lot of people had gone there or had relatives there, and they wanted to see some kind of acknowledgement or reference to it,” says Henri. “Without talking to them, we would never have known how much that mattered to them.” Consequently, the exterior landscape includes a monument with a plaque.

“One of the things that has come up a lot within indigenous communities is that they want to see their Native languages reflected in their buildings,” Henri adds. “There are more than twenty distinct Native languages here, and many communities are trying to rebuild them after decades of not being encouraged to use them.”

The Dena’ina Health and Wellness Center in Kenai was designed to represent the culture of the Dena’ina people, who were the original inhabitants of the Upper Cook Inlet region. Architectural details throughout the building represent the history of the area and its people, including century-old Douglas fir planks (reclaimed from a Kenai River cannery) that span much of the interior. The ocean is depicted in blue across the floor near the main entrance; agates inset in the flooring were collected by tribal members, and Dena’ina names are used throughout the facility.

Architects Alaska also worked on the expansion of the Tanana Chiefs Conference Chief Andrew Isaac Health Center in Fairbanks, working with the Athabaskan Native community to include cultural references when the existing ambulatory clinic was enlarged to include operating rooms and more service lines for cancer treatment.

Stantec | Wayde Carroll Photography

Architects Alaska worked with the conference’s cultural committee to include a cultural gallery on the first floor where Native art and artifacts are displayed. The building also features large graphics of medicinal Native plants on the walls of the exam rooms, such as those used to treat arthritis naturally. A curved linear wall references the rivers that are so important to the people of Interior Alaska.

“This community lives a traditional lifestyle based on Russian Orthodox beliefs and doesn’t socialize much outside of their community,” says Henri.

The village near the head of Kachemak Bay has no road access, so everything must come in by barge, boat, or plane. “It was interesting learning what was most important to them,” says Henri of the ongoing project that is currently awaiting more funding. “What we came up with is an almost residential-looking school with sloped roofs, wood elements, and an exposed structure that makes it more friendly and hospitable.”

Henri adds that the cultural responsiveness was less about the built form but more about how designers worked with the community to discover its needs. What Kachemak Selo needed, it turns out, was a building that fits the scale of the village.

“Unlike most schools, which are masonry castles that can last for fifty years and stand up to graffiti, this building is for a small community of people, and it needs to be in scale with that,” Henri says. “It is also a little more hospitable and approachable than a standard school might seem.”

In any given building, “We hope most of all for the users to see this as home. To feel, ‘This is ours.’ We want them to take possession of it and for it to be their building,” says Henri. “An architect is most successful when people forget that they are involved.”

The designer’s job is to interpret the community’s wishes and then step out of the way. “The best compliment we’ve ever gotten was when a Native corporation leader walked into the Dena’ina Health and Wellness Center and said, ‘This place really sings Dena’ina,’” Henri says. “It was an extraordinary compliment to hear that we’d gotten that close to reflecting elements of their culture and helped them feel that the building belonged to them. That’s when you know you’ve been successful—when it speaks to the people who use it.”

The Kahtnuht’ana Duhdeldiht campus evoked a similar response. “I was sitting on a plane next to a woman from Kenai when she started talking about the library,” shares Gambardella. “She said that her husband, who was terminally ill, used to go to the library every day because the lounge space had windows and a fireplace, and he could sit there and enjoy the sunlight among his community.”

Gambardella recalls almost crying on the plane. She says, “It was very touching to hear that we are creating spaces that are so community-minded. That us really thinking about who uses this space is important.”