he arrival of COVID-19 last March changed the way Alaskans live. Hand sanitizer and face masks became must-have items when leaving home, and phrases like “hunker down” and “social distance” became part of our daily lexicon.

The pandemic also dramatically changed how Alaskans, like much of the world, do business. Restaurants and retail stores relied heavily on delivery and curbside pickup options to help offset the loss of foot traffic, while the office workplace transitioned overnight from the traditional in-person model to an entirely—or almost entirely—remote workforce.

“I think people who work in offices have been lucky,” says Giovanna Gambardella, principal and architectural services manager with Stantec. “We were able to quickly move our workstation from the office to home.”

Eventually, though, Alaskan workers will return to the office, assuming they haven’t already. The COVID-19 pandemic has caused a shift in thinking among business leaders about what constitutes the ideal workspace, whether it’s a move to hybrid work schedules or open layout design concepts that are conducive to team collaboration and provide flexibility to accommodate changing health and safety recommendations.

“Just from a general standpoint, I think what’s evidenced by projects the last nine or ten months is this ultimate need for flexibility,” says Kelsey Davidson, principal with SALT. “So, creating a multi-functional space that can flex with changing needs.”

Though the pandemic helped catalyze the shift in thinking among office-based businesses, many of the design changes currently being implemented aren’t necessarily new. Instead, they are catching Alaska offices up to already occurring trends and aligning the workspace with recommendations designers and architects have suggested for years.

“There’s no such thing as COVID-specific changes,” says Dana Nunn, interior design director at Bettisworth North. “Designers are simply implementing a complement of best practices in interior spaces to manage air quality, thermal and acoustic comfort, choice, and support the needs of the worker.”

Which of these best practices are put in place depends largely on the specific needs of the business.

“The public just wants a fix, but there isn’t a single fix,” Nunn says. “Everything is so nuanced. What you do is so dependent on what your operation can withstand.”

Principal, SALT

Bettisworth North

Bettisworth North

Traditional office workplaces arguably had the most seamless transition.

“If you look at the spectrum—there’s office workspace, retail, and healthcare—the office is obviously probably the easiest adaptable user,” says Carel Nagata, associate and senior architect with Stantec. “Most office work is done with computers, so it doesn’t really matter where you do your work.”

Non-essential businesses quickly moved to a work-from-home model. For businesses unable to switch to a fully remote workplace, changes to workspace layout and design helped minimize the spread of the virus.

“We [saw] small changes that happened right away,” Gambardella says. “Putting screens up, there are wellness stations in the office space. When you get in, one station has hand sanitizer and masks. So, I think there’s a thought about how to design these so they’re visible and kind of user-friendly.”

Other changes to the workspace layout, including spreading out workstations, using desks and conference room chairs as natural barriers to encourage social distancing, and adding visual reminders to wash hands and wear masks, also help protect employees and clients, Nunn adds.

But even this relatively easy transition had its share of challenges. Businesses that went virtual had to evaluate their technological capabilities to determine whether the appropriate devices and infrastructure were available to their employees. Whether employees even had the necessary bandwidth to connect virtually from home also became an issue.

“There’s a technology investment right off the bat,” Nunn says of switching to a remote workspace. “You may need to completely change over your technology.” That could mean switching from desktop computers to laptops or implementing a remote VPN. And while those changes might solve the technological concerns, they could still impact the office design, she adds.

“Potentially for some companies, the technology requirements mean that they need more server space, or they may need a bigger area for their IT department to handle their at-home employees,” she says. “You may just need different things to make that work.”

Bettisworth North

Bettisworth North

“Cleaners that folks are using are designed for non-porous surfaces, but people are using them on everything,” Nunn says. “And if you’re using them on things that are porous, you can really rapidly degrade your wood surface, plastics, paint, and some upholstery.”

That’s led to conversations with clients about choosing finishes and materials that aren’t usually seen in an office setting but are ultimately better suited to today’s heightened cleaning protocols.

“I think what we’re looking at more is cleanability, making sure that the material that we put on something is compatible with how maintenance staff is able to service those items,” Davidson says. “So, instead of planning on luxe tweeds or woven fabrics, you might see more bleach-cleanable products.”

For high-traffic areas like waiting rooms and reception areas, furnishings typically seen in healthcare settings may become more popular.

“Luckily, healthcare type upholstery has come a really long way in the past ten years or so,” Davidson says. “It’s not crunchy, super high-gloss vinyl. It’s definitely improved significantly, and a lot of fabrics really are soft to the touch. So that’s nice because obviously, you want to put your best foot forward in your waiting area.”

Designers are also making changes to high-touch areas like doorknobs and reception areas.

“Door hardware—can you push it with your [hip], use your foot? That’s simply a hardware change,” Nagata says. “Keycards to activate the door; it used to be just accessibility, but now everybody will use them so they don’t touch it.”

“A lot of what we’re doing is helping building owners and operators understand the system that they have, the filtration system that they have, and what are the options if they want to change the existing system,” she says.

Along with decreased occupancy and other protective measures, ensuring adequate ventilation and filtration in the office to help flush out the virus became an increasing priority. One option to improve indoor air quality is to increase the volume of outside air coming in.

“All occupied commercial buildings have a minimum outside air volume,” Winfield says. “That’s a calculated level that’s based on the number of people in the office space, the programming, and the square footage.”

High-density spaces, like conference rooms, have a higher outside air minimum than a private office, she says. Having 100 percent outside air pulled into the building would be ideal from a virus-protection standpoint—but not an energy-efficiency one, she says. So, not only is this often a cost-prohibitive solution, it’s also not feasible unless the system was specifically designed for it, which is typically not the norm in Alaska, she explains.

Instead, Winfield sees businesses focused more on ensuring that their building’s ventilation system is operating as intended and determining appropriate filtration levels.

Filtration pulls contaminants from the airstream, thus minimizing what goes into occupied spaces, she explains; the higher the filter’s MERV (minimum efficiency reporting value) rating, the more particles filtered out of the airstream. But installing a filter with a pressure drop that exceeds the fan’s capabilities can also reduce the building’s airflow, a problem that can sometimes—but not always—be remedied by increasing the fan speed.

“We’re seeing the effort being spent on treatment and filtration, so that’s a higher level of filtration or something like UV-C [ultraviolet-C light], which kills the virus in the air stream, as opposed to a higher outside air volume,” she says. “I am seeing both; I just see more on the filtration and treatment side.”

Design Alaska

“I think the pandemic is going to be the catalyst for the business community to do what the design community has been saying to do for years,” Nunn says.

And that’s a move toward an open-concept layout that provides more space for team collaboration and the flexibility to reconfigure the space to meet changing needs–whether due to a pandemic or not.

“What’s great about an open office is it already allows for flexibility,” Davidson says. “There are no walls in place, you can easily move furniture around, do a supplemental furniture order, or add on pieces and elements that provide screening between individuals.”

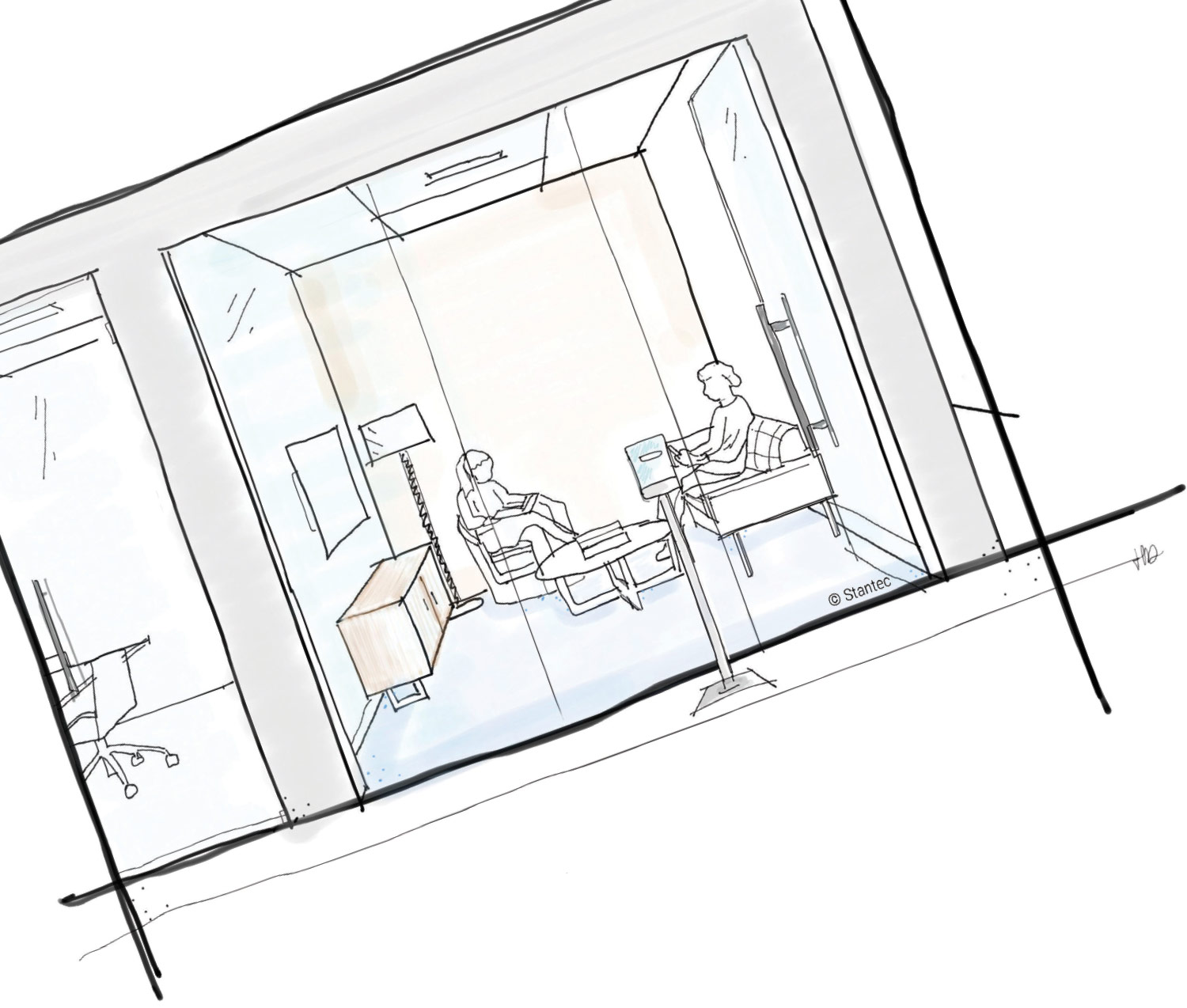

Stantec

A nationwide survey Stantec conducted of its clients anecdotally bears that out. Gambardella says that 86 percent of survey respondents say they envision a workplace model where employees go into the office only one to three days a week. That switch in viewpoint changes not only the purpose of the workspace but, with it, the ideal layout.

“From a design standpoint, I think that suggests that the main purpose of the office is changing from being kind of a center for individual focused work to a hub where people meet,” Gambardella says. “The potential activity of the space is going to change because perhaps not everybody is going to own a cubicle. I see more kind of soft areas where people have conversations, and nobody claims a specific space.”

Nagata agrees. Though she says the pandemic highlighted how much people overlook the social aspect of going into the office, she anticipates that office space will be designated for specific activities, with private offices being reserved for small meetings or telephone conversations and open workstations being used at-will by employees when they come into the office.

“I think we’re going to lose the dedicated workspace,” she says. “I think maybe there will be more of a demand model, more of a status thing.”

And that change can lead to an increased reliance on technology not just when employees are working from home but when they come into the office as well.

“I’m thinking technology is going to be more important to interacting with the building now,” Nagata says. “It used to be [that] you went to the office. Now, it will be, ‘We have an app to reserve the room, an app to say you’re in the office.’ All of a sudden, we’re going to use technology more.”

While the December rollout of the COVID-19 vaccines means a light at the end of the tunnel is in sight, Nunn says its effects on workplace design will likely last much longer than the pandemic that prompted it.

“It’s definitely a continual thing,” Nunn says. “I think we’re going to see the effect of this for years, and hopefully the solutions we’re implementing for COVID will give us the flexibility to respond to other situations.” ![]()