laska Native corporations are for-profit enterprises with a unique community focus.

“All shareholders are entitled to benefits of Alaska Native corporations,” says Andrea Gusty, president and CEO of The Kuskokwim Corporation (TKC). In addition to their commercial investments, regional and village corporations invest in community projects that often fill the gaps where business, nonprofits, or government can’t quite reach.

Or, as in the Bristol Bay region, facilitating the reach of a government office.

“In evaluating the needs of our shareholders and their communities, we identified that one of the barriers from getting a job is not having a driver’s license,” says Carol Wren, senior vice president of shareholder development at Bristol Bay Native Corporation (BBNC). “With the lack of DMVs in many smaller communities, this is a significant issue.”

The Kuskokwim Corporation

BBNC worked with the Alaska Division of Motor Vehicles to develop a driver’s test route in communities that could accommodate one, and proctors were trained to tutor locals for the written test. “We had to find proctors before the DMV even showed up,” shares Wren. “This led to a lot of planning and conversations on how we could pull all of these components together.”

The first mobile DMV unit consisted of three employees. “They were just starting to use a mobile unit for taking and downloading photos,” says Wren. “We didn’t have Starlink yet, so we had to make sure we had internet.”

BBNC worked with the local tribe and housing authority to check for an applicant’s physical address, not just a post office box. “Those were the minor things that prevented people from getting the necessary documentation required for Real IDs,” explains Wren.

Tyonek Native Corporation

Workforce and professional development also motivated some of TKC’s community projects. TKC is a joint corporation for ten villages in the Middle Kuskokwim region, and those villages remain the focal point of TKC’s ongoing community projects.

Gusty says TKC examined the needs of individual shareholders. “For example, it’s not just providing heavy equipment training; it’s also about making sure they have access to that training closer to home, as family needs cannot be overlooked,” she says.

To address this and other workforce needs, TKC opened the Arviiq Regional Economic Development and Training Center in Aniak. “Utilizing this model, we can provide community members with access to online training,” explains Gusty. “They can complete the first level of training virtually, then come into Aniak for the next level, using the program as a stepping stone to something else. Our goal is to be mindful of the whole person’s needs as we’re providing services.”

Koniag, the Alaska Native corporation for the Kodiak Island region, supports workforce development in its communities. “We have supported CDL [commercial driver’s license] and forklift training programs as well as 6-pack certification classes [for operating boats holding up to six passengers],” says Koniag President Shauna Hegna. “We commit our time to support these nonprofits that are doing good things in our community.”

For careers in natural resources, this year saw the debut of Koniag’s Young Environmental Technician Intern (YETI) program.

“Amy Peterson, a community liaison working with us through a partnership with Kodiak National Wildlife Refuge, came up with the idea of creating an internship program focused on getting some of our younger folks interested in careers in the natural resource disciplines, be it timber operations, forestry, biology, or environmental studies,” says Tom Panamaroff, Koniag’s regional and legislative affairs executive. “In the first year of the YETI program, we had four young people between the ages of 15 and 17 involved.”

Peterson reached out to the Alaska Department of Fish and Game and the Kodiak National Wildlife Refuge Visitor Center to design the six-to-eight-week internship. “With the input of these groups, we discovered a plethora of things the YETIs could do for their program. All of it involved being outside, working with their hands, and getting a taste of the different kinds of things that can become careers in the natural resource disciplines,” says Panamaroff. “We hope to add an additional program for the 18-to-21 age group in the future.”

“We have an incredible lack of housing inventory, which impacts every aspect of life in our communities,” Hegna says. “For example, several teachers have accepted contracts and later rescinded them because of a lack of housing. The same holds true for hospital workers. We’re now at a point at which the lack of housing is impacting the professions that keep our communities happy, healthy, and productive.”

Koniag

Finding affordable land to meet the housing needs presents additional challenges on Kodiak Island. Fortunately, the Kodiak City Council recently approved the sale of 6 acres to KIHA to support the self-help housing program.

“It’s really exciting because the first phase of this program will result in ten new homes,” says Hegna. “This is significant considering they have only had one or two homes built in Kodiak in the past couple of years.”

TKC is also tackling the need for affordable housing in the Yukon-Kuskokwim region. “The regional housing authority estimates that, at the current rate of fifteen new homes a year, it would take 200 years to meet today’s demand for housing,” shares Gusty. “We are currently working with the US Forest Service, the National Renewable Energy Laboratory, the Cold Climate Housing Research Center, and the Denali Commission to develop a way to sustainably and responsibly harvest some of the timber on our land to build homes to tackle our housing crisis.”

Utilizing an innovative design, builders would be able to use shorter pieces of wood, which maximizes the use of the tree. “It’s more of a LEGO model than a traditional log cabin,” says Gusty. “The piece-en-piece system we borrowed and adapted from Canada’s Indigenous communities takes more effort on the milling side but is much more energy efficient and easy to assemble. Each piece is numbered, which corresponds to step-by-step instructions. Three people will be able to build a house in two days.”

Knowing that energy infrastructure would take time and planning, TKC chose to do something with an immediate impact. “We provided and installed LED light bulbs for every home in our ten communities,” she says. The energy-efficient bulbs instantly reduced monthly electricity bills.

Long-term energy solutions are still part of TKC’s vision. “We’re working our way up to not only fixing some of the widespread energy issues that lead to power outages but also focusing on renewable energy projects in each community,” shares Gusty. “We’re also in partnership with the local energy company in Lower and Upper Kalskag studying wind and solar energy projects.”

Beyond energy bills, TKC is also helping its communities with their food bills. A subsidiary operates the Kuik Run Store in Aniak with the mission of lowering the cost of living for TKC shareholders. “This is unlike any of our other businesses in the Lower 48,” explains Gusty. “We are not looking to make a profit on this business venture; rather, it is an investment in the community to provide items needed while lowering the cost of living.”

Food prices are also on the agenda for Cook Inlet Region Inc. (CIRI). One of its special projects involved Ninilchik Village Tribe’s Elder outreach program.

“The Elder outreach program provides over 100 Elders food security, connection through gathering, cultural activities, and holistic care,” says Darla Graham, director of stakeholder engagement. The program helped provide locally sourced, traditional foods, like moose and salmon, for Elders.

One of the village corporations in CIRI’s region is addressing food security in another way. Tyonek Native Corporation (TNC) is supporting a garden in the village on the west side of Upper Cook Inlet.

“Every summer an amazing young youth crew works on the Tyonek garden,” says TNC Chief Administrative Officer Connie Downing. “This collaborative project situated on TNC land is really expanding. In the garden they are growing garlic, celery, potatoes, flowers, and traditional plants for the community. A weekly farmers market provides residents with the opportunity to obtain fresh, healthy food.”

“This is very important to the lifestyle and culture of the Tyonek residents and shareholders,” says TNC’s senior Alaska operations manager Jamie Marunde. “The project was accomplished in collaboration with numerous entities, including the Tyonek Tribal Conservation District, the US Fish and Wildlife Service, US Department of Agriculture Natural Resources Conservation Service, Alaska Department of Fish and Game, Alaska Department of Natural Resources, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association, CIRI, the Tyonek Tribal Council, and several contractors including Tyonek Contractors, which employs many of our shareholders and played a significant role in the culvert project.”

Cape Fox Corporation

TNC and the village’s tribal council joined forces to create a task force to oversee community projects. “The task force was developed for us to collaborate instead of working independently,” says Downing.

The partnership’s projects include coastal erosion, economic development, fire protection, infrastructure, natural resources, recreation, and social services. “We’re working together on an image to show what we would like the village to look like in the future,” says Downing. “That includes a new fire station, a new building for a grocery store, boys’ and girls’ clubs, recycling stations, and a helipad for medevac.”

“We take a thoughtful approach to community outreach and support while striving to be a good community partner. This is what everything is based on,” says Graham, a CIRI shareholder herself. “Our goal was to find an equitable way to spread the love around to all of the tribes while encouraging and supporting each community.”

As a result, CIRI established a tribal grant program last spring, in addition to its community outreach, and the grants have funded a variety of projects so far.

“The application process is simple, unlike more administratively burdensome grants,” explains Graham. “Funds from the program can be used for any project benefitting the tribe that falls within one of the three categories: subsistence, self-determination, and revitalizing of culture and identity.”

Revitalizing culture is also a goal at Cape Fox Corporation (CFC), particularly through its nonprofit affiliate. Cape Fox Cultural Foundation (CFCF) delivers educational and cultural services to the public to preserve and support the heritage, culture, and future of the village of Saxman and Southeast more broadly.

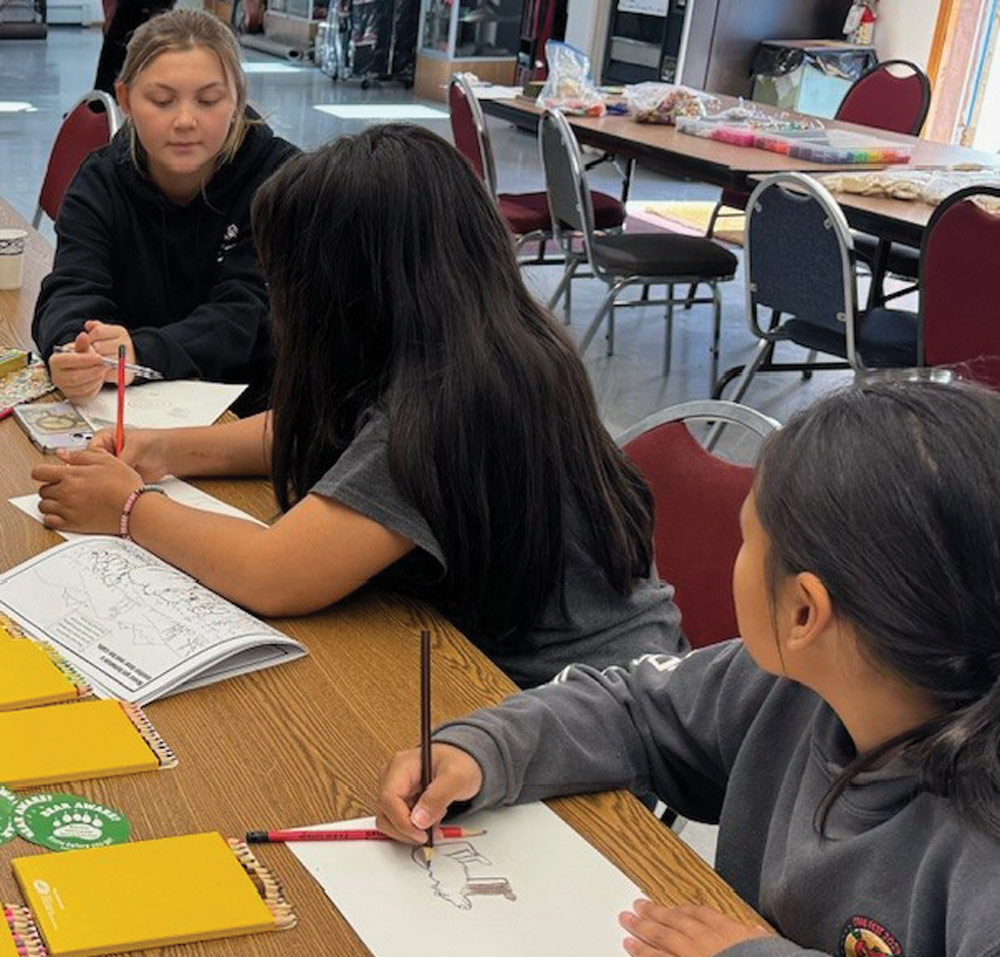

CFCF also focuses on preserving culture, educating the youth, and strengthening the community, thanks to recent partnerships and funding opportunities provided by Rasmuson Foundation, Alaska State Council on the Arts, and Museums Alaska.

“We wanted to create an open workshop—a place where everyone can gather on a certain day to learn and work on cultural art traditions,” says CFC board member, shareholder, and resident artist Kenneth White. “The Tier One funding allowed us to get the classroom tables, chairs, benches, cabinets for art materials, and health and safety items needed.”

Jamie White, project manager for CFCF adds, “We established our first workshop on August 24 and have held workshops every Saturday since as we continue to grow.”

CFCF plans to continue its efforts in securing funding through grants and fundraising to further projects in the community.

Whether through a nonprofit foundation or more directly, Alaska Native corporations for regions, villages, or joint areas like TKC fulfill their unique mission alongside their commercial ventures.

“We’re approaching this in a holistic manner,“ says Gusty. “You can’t just build affordable housing if energy is unstable or if the resident doesn’t have a way to pay the mortgage.”