laska’s largest philanthropic organization, the Rasmuson Foundation, announced $550,000 worth of grants to thirty-six artists across Alaska in September. The awards, and the recognition that comes with them, are coveted in the relatively small art world of Alaska.

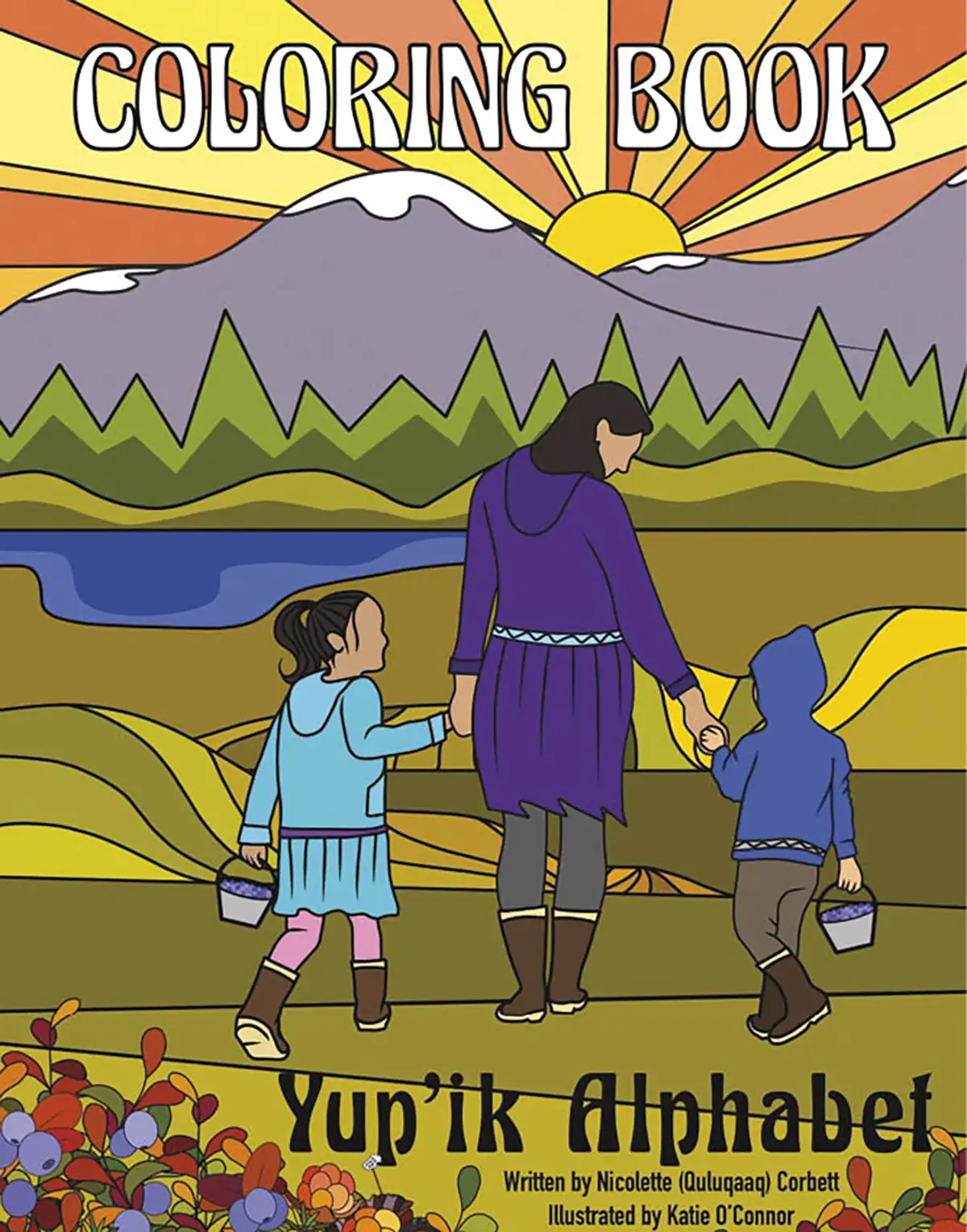

“I’ve been applying for the Rasmuson grant since my business started in 2015; I just haven’t been able to find an ‘in’ with it,” says Nikki Corbett, who sews and travels around the state teaching qaspeq sewing classes. “I was really surprised that we got it. It’s really exciting that it’s going to finally come to fruition.”

The Individual Artist Awards—unusual in the fact that they are awarded to individuals instead of nonprofit or tribal entities—come in the form of $10,000 project awards, $25,000 fellowship awards, and a single $50,000 Distinguished Artist award. A jury of art professionals from outside Alaska make the award selections.

The batch announced in September is all the more precious because they are the last grants coming from the Rasmuson Foundation in the near future. The organization is closing applications while it pauses to regroup and refine its long-term goals.

When her daughter was born in 2017, Corbett began looking for Yup’ik language learning tools for early readers. She grew up in Bethel, where there is a Yup’ik language immersion program, but that was not available outside Bethel. She didn’t find many tools for teaching Yup’ik to early learners, either. It became her goal to create such tools and make them widely available.

“I said, ‘I know grants; the hard legwork is done. Let’s not give up, let’s keep applying,’” O’Connor says. “So we kept on, and we simplified it.”

They narrowed the idea to self-publishing the coloring book. That idea was a hit with the Rasmuson Foundation Individual Artist Award panelists, and they received the grant.

Corbett and O’Connor have already made significant progress on the coloring book. In consultation with other Yup’ik speakers, Corbett has been selecting words that are well-suited for a coloring book—easily depicted and culturally relevant. For example, M is for Maqivik, the Yup’ik word for steam bath.

“We do things that are incorporated into our lives,” she says.

Parker is a first-generation Filipino immigrant and longtime resident of Ketchikan. Growing up in Ketchikan’s large Filipino community, she took part in Filipino dance, she says, but knows very little about the dances she learned as a child.

“You were sort of forced to do it; there was no real perspective on story, interpretation, and reflection of the dance. As a child, you don’t question authority; you don’t understand what you’re learning and what the movements represent,” Parker says.

As an adult, she has been active in youth dance culture and is the head coach of the Ketchikan High School Dance Team, as well as the head instructor and owner of studioMAX, a dance and fitness studio. Parker wants to bring Filipino dance back to Ketchikan in a culturally rich way.

Alma Manabat Parker

She has used a portion of the Rasmuson grant to travel to the Philippines with Kayamanan ng Lahi, a Filipino dance and arts organization from Los Angeles she is partnering with. With the group’s help, she attended a Filipino folk-dance national workshop in July, learning eleven different types of dances from people from different regions of the Philippines.

“I know if someone doesn’t do this, it’s not going to last. I want to pass on that knowledge and the meaning behind it. My intent is to go back to the Philippines and have a longer stay, visit different regions, learn more, get regalia and instrumentation, authentic gongs and drums,” she says. “My ultimate dream is to have a diverse cultural center where all walks of life could have space to practice what their traditions are.”

And that’s all… for now.

With the release of the September grants, the foundation begins a year-long pause in grantmaking. The Rasmuson Foundation Board will meet again this month to award end-of-year large grants to various programs, but it currently is not accepting new grant applications for its Tier 1 (up to $25,000) and Tier 2 (larger than $25,000) grants, nor is it accepting applications for 2024 individual artist awards. Rasmuson staff have listed mid-2024 as the likely timeframe when application periods will reopen.

“The last year was a really big year for Rasmuson in the number of awards we made. We saw more large transactions, more large donations than in the past. We have a little digestion to do,” says Vice President of Programs Chris Perez.

In the past five years, the Foundation has distributed an average of $28.8 million each year.

The foundation doesn’t simply receive a funding request, decide whether or not to fund it, write a check, and move on. Receiving Rasmuson funding is a little like building a friendship: often grantees start with a Tier 1 funding request for a small project such as new flooring, a van, or technology upgrade, and then step to a larger Tier 2 request. That involves significantly more work on both sides, Perez says.

Nikki Corbett

By the time the grant process is complete, the staff has worked with the grantee or applicant, leadership, community stakeholders, and other funders. Then comes the Rasmuson Foundation board decision on whether to award a grant or investment. Those decisions, Perez says, happen on a semi-annual basis.

The Tier 1 process is simpler. Applications were accepted year-round and reviewed on a rolling basis. While there is no requirement for matching project funds, applicants need to demonstrate board and community financial support of their overall budget.

“We want to invest in organizations that invest in themselves,” Perez says.

The foundation also wants assurance that the request fits the broader community’s needs.

Since the Rasmuson Foundation was created by Jenny Rasmuson with a $3,000 endowment in 1955, the organization has distributed $515 million to benefit Alaskans. That first grant? It was for $125 to help fund a church’s “motion picture projector,” and Jenny Rasmuson paid the balance of the $300 cost herself.

Elmer’s son, Ed Rasmuson, became a third-generation banker. In 1999, he negotiated the sale of National Bank of Alaska to Wells Fargo. The proceeds of the sale poured into the family’s philanthropic endowment, “launching a new level of giving,” as the foundation’s website says.

Ed Rasmuson stated that the foundation gave away half a million dollars a week, a statement that still holds up. He died in 2022, having chaired the foundation’s board from 2000 to 2021, when he became chairman emeritus until his death.

For much of that time, Diane Kaplan—who was also the foundation’s first employee—served as CEO. Having steered the foundation through the unsteady times of the COVID-19 pandemic, Kaplan retired in early 2023. The board selected former Alaska legislator and healthcare manager Gretchen Guess as the next president and CEO; she went to work at the end of February.

While her first year has been busy, now Guess is taking time with the rest of the foundation’s leadership to regroup, refocus, and recharge. She explains, “The main reason for the pause is really to allow the staff… to catch up on their work, document the processes, and do some internal alignment work that, because of how fast the team has been going, it hasn’t been able to catch up on it.”

Guess adds, “The board, which in some ways is different with Ed’s passing, will have time to relook at some internal governing items that have not been updated, to look at some short-term process improvements and some long-term strategic planning.”

Ultimately, Perez says, pausing for a few months is a chance to reflect on where the Rasmuson Foundation has been.

“This is an organization that has been growing rapidly and running hard for three decades. I’m excited by the opportunity to both reflect on what we’ve done, think about the successes we’ve had, and set the course for where we want to be,” Perez says.

And that takes a little time. As Guess says, “This is a big boat that moves slowly.”