021 has not been a post-pandemic year. Vaccine rollouts in the beginning of the year spelled hope for many and led to a broader reopening of businesses. Summer saw a return to travel and other normal activities. But overall, an uncertain economy, goods shortages, and a third-quarter resurgence in COVID-19 cases has made it clear that the pandemic is still very much with us, along with many of its lingering side effects.

What impression has COVID-19 left on 2021? Where are we in the pandemic, and what has Alaska learned so far?

The lessons are basic, and the message is simple: Be prepared, be flexible, and mind your mental health.

“From an infection prevention lead position, I think the most effective strategy we employed early on in the pandemic was coming together as a leadership group and mobilizing around the most pressing needs of the day,” says Providence’s Manager of Infection Prevention Rebecca Hamel. “I don’t typically sit at the executive level; it really allowed me to have access to leadership.”

With personal protective equipment, for example, Hamel says her team had to navigate supply chain constraints and find alternative sources.

“There were a couple of times the decision we made at the beginning of the day was a different decision than at the end of the day,” she says.

“You have to work fast to win,” says Dr. Michael Bernstein, Providence’s regional chief medical officer. “We made a decision, we did it, and then we would adapt. It was a little different than the usual pattern; in quieter times, we had longer meetings and maybe six months of planning, but in this we had to work very quickly.”

Providence set up its first drive-through COVID-19 testing site in just days. Advice about whether patients should be intubated early in their treatment also changed. Best practices, such as putting patients in a prone position, face down, proved to be effective at helping them breathe. Non-invasive breathing support tools have also proven effective. Staff learned how to conserve protective equipment. Everyone learned that masking and social distancing really did help reduce the virus spread. Those rapid shifts in thinking are still happening today, Bernstein says.

Elizabeth Paxton, Providence’s regional chief nursing officer, says finding best practices for keeping workers safe while continuing to provide top-level care for patients was crucial.

“We’re surging again and experiencing some changes,” she says. “Having those communication mechanisms, especially as large as we are, [is key]. And to try to be as consistent as we possibly could, so we can be a single source of truth.”

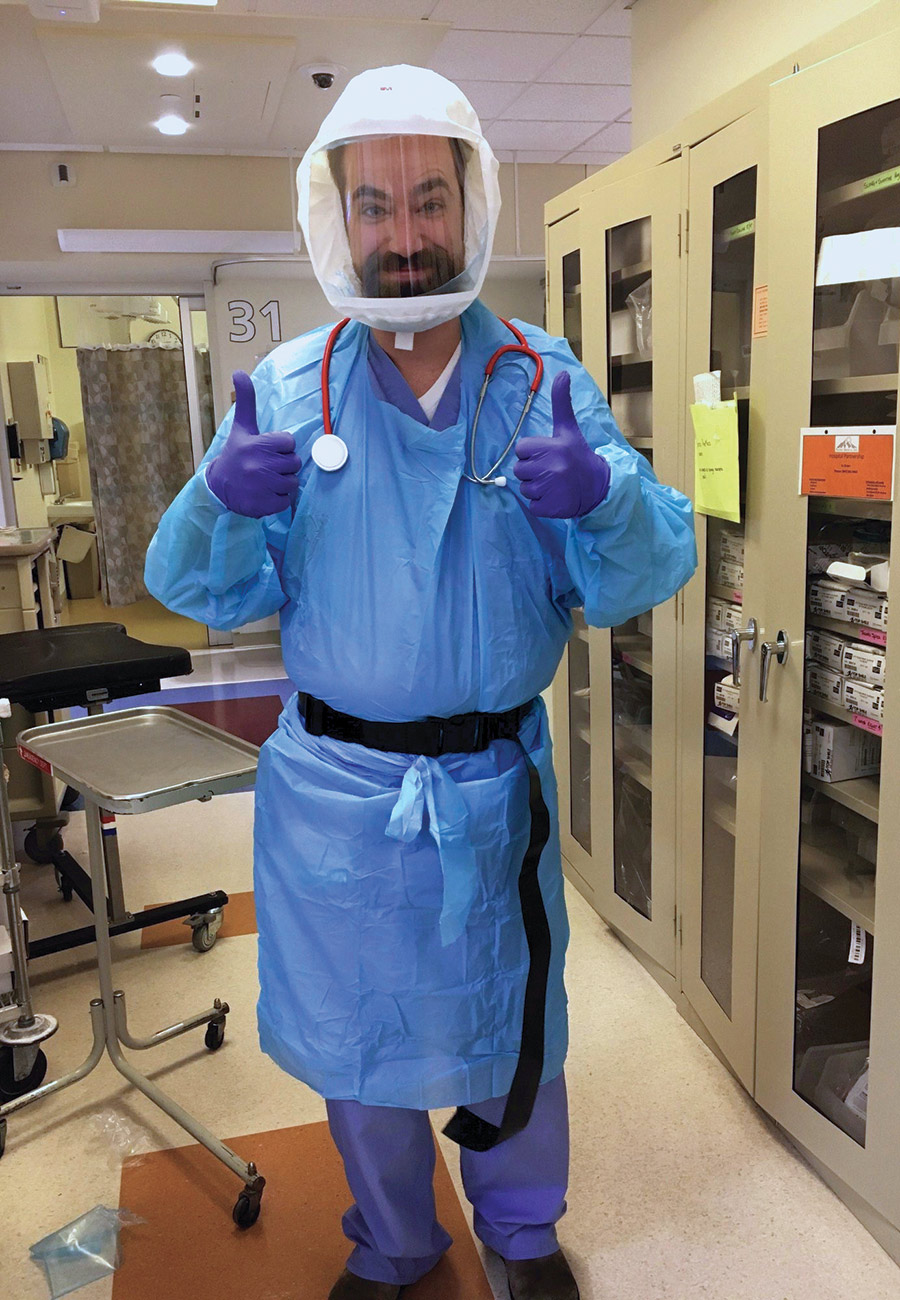

Helping workers understand and effectively incorporate the changing protective equipment rules and changes to day-to-day care practices has been very important in keeping workers safe, Hamel says.

One way her team has done that is by using a strategy she first picked up via the social media platform Twitter. She’s part of an infection prevention group that posts regularly—a professional outlet that has been helpful during the high-stress days of dealing with the pandemic, she says. A post she saw showed a staff member with a white vest labeled “safety monitor.” A person in this role is regularly on the floor, stocking supplies or simply doing rounds with staff. Hamel and her team incorporated the idea and found that doing so opened the door for encouraging staff to use protective equipment properly, helped the infection preventionists recognize recurring problems or fatigue—someone putting used gear on the “clean” cart instead of the “dirty” cart, for example—and helped her team to see if a workflow was too cumbersome, so a different solution could be found.

Providence Alaska Medical Center

Providence Alaska Medical Center

Nearly two years into the pandemic, Paxton says the emergency incident-command style of communication that was used at the beginning of the pandemic is still somewhat in effect, although in a hybrid fashion.

“We are trying to understand how to incorporate COVID response daily. It is challenging us to come up with, ‘What if this is the norm? What if this is the state that we will be in in the next six months?’ Fatigue is something we are also trying to combat,” she says.

Providence, with typically around 5,000 employees at locations around the state, received 140 workers to use in various locations. Paxton says the emergency temporary workers included registered nurses, certified nursing assistants, and respiratory therapists. The temporary workers are on hand through December 19.

“They’ve been very, very helpful; our staff has been very relieved,” she says.

The out-of-state workers aren’t expected to be in Alaska long-term. Alaska Department of Health and Social Services Commissioner Adam Crum likened the worker shortage to a disaster scenario.

“We had record high hospitalizations, record turnover at hospitals, the hospitals were running at redline,” Crum says. “This was a true emergency situation. Think about it as, basically, Red Cross workers.”

Bernstein says it underscores the need for training a new workforce.

“We knew we were heading toward a workforce crisis in healthcare in the next decade, but the pandemic absolutely sped that up. It emphasized for us how much we need to take care of our workers, to be attentive to their mental care, their family needs. They are the foundation of what we do and we have to be much, much more proactive about that and develop our own supply chain for the workforce. We have to encourage young people to go into healthcare… so we can have a strong future, caring for the community,” he says.

Alaska Public Health Director Heidi Hedberg says the state is continuing to work with hospitals and universities to develop a plan. Expect to see more about that soon, she says.

“There has always been a healthcare workforce shortage. What is different is that we have an exhausted workforce, and they are leaving the industry. Before the pandemic, there was interest and desire to address the workforce shortages but the parties lacked funding or programs to expand workforce trainings. Now we’re trying to nail down what we can do… to get more Alaskans to enter into the healthcare sector,” Hedberg says.

By starting the discussion about vaccines in July 2020, months before any vaccines were available, Hedberg says plans were laid for a collaborative rollout. This was a lesson learned from the early days of the pandemic when the federal government sent testing supplies.

“The federal government… was pushing testing supplies to the state and through Indian Health Service. We saw some communities that had a lot of testing supplies and some communities that didn’t have any,” she says.

Providence Alaska Medical Center

Providence Alaska Medical Center

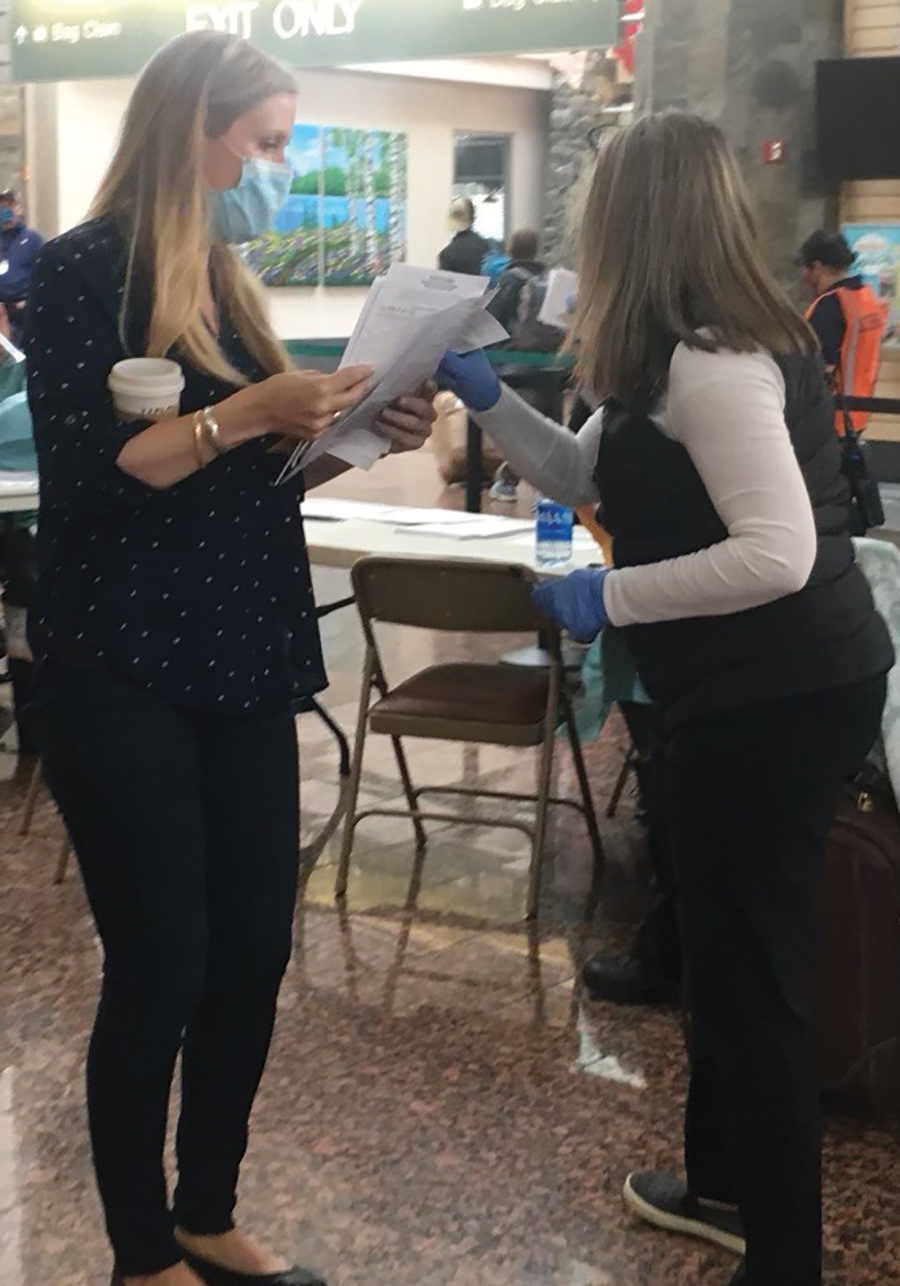

Hedberg explains, “We stood up testing sites at three major and seven smaller airports. We have continued testing and added vaccines.” Since the sites opened, 5,452 people have been identified as COVID-19-positive as they traveled through Alaska airports, she says, and 6,206 people have gotten vaccinated at an airport site.

“We stood that program up in eight days,” Crum says. “There was a lot of work done in a very short time by [D]HSS and Transportation—and the mobile website [Covidsecure] was up by that time, too.”

Providence Alaska Medical Center

Providence Alaska Medical Center

The state continues to use the collaborative model to offer new services to Alaskans.

“Now we are using that model with monoclonal antibodies and possible future therapies as well,” Hedberg says.

The monoclonal antibody treatment, seen as an effective tool in reducing severe COVID-19 cases, was made available first to hospitals, she says, but the logistics of administering the therapy was initially hard to overcome due to time and space. For some hospitals, infusion labs are where high-risk patients are treated, and potentially exposing them to COVID-19 seemed risky. So Public Health set up an infusion center at the Alaska Airlines Center in Anchorage, demonstrating that the monoclonal antibody treatment can be done “in a group setting that is safe and effective,” she says.

“Then we started to see it was a little like wildfire. It started in Anchorage and rolled out to other communities. We saw this evolution of a process for administering monoclonal antibodies,” Hedberg says. “We are aware there are future therapies that are out there going through the administrative process of the FDA. Together we can make sure that all Alaskans have access to those as well.”

Ultimately, like all of us, Crum and Hedberg say they are ready to move on to new challenges.

“We know the public is tired of COVID, but thank you for pulling through this together and we look forward to 2022 and focusing on physical activity and mental health,” Crum says.

Hedberg says she wants to boost Alaskans’ knowledge that the basic tenets of good health—sleep well, eat healthy foods, and move your body—are the best tools to boost general respiratory health and overall happiness. She is looking forward to that message being the prevalent message she gets to deliver in 2022. ![]()