arlier this summer, the Southeast community of Angoon came together to celebrate the arrival of new jobs, clean power, stable electricity rates, and a government award of $26.9 million.

The “Thayer Celebration” was an opportunity to recognize the considerable efforts that led to the 850 kW Thayer Creek Hydroelectric Project, now slated for construction on Admiralty Island.

Attendees included representatives from US Senator Lisa Murkowski’s office and the US Forest Service, among other influential parties involved in the project’s conception.

“The community has rallied around this project,” says Jon Wunrow, project manager for Angoon’s village corporation, Kootznoowoo. “It’s a great example of a federally recognized tribe, a rural Alaska community, a village corporation, and the federal government working really well together.”

With a $34 million price tag, Thayer Creek is just one (albeit glistening) example of many energy infrastructure improvement projects across Alaska that are receiving a pivotal source of funding, some of which have been decades in the making.

In terms of government funding, Alaska finds itself in a modern gold rush. Key programs from the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act of 2021 have created a generational opportunity for energy improvements—particularly for rural or remote communities. And those tasked with guiding the state to a more stable, sustainable energy future aren’t taking the flow of funds for granted (so to speak).

Just look at the Susitna-Watana Hydro Project, says Jacob Pomeranz, a senior electrical engineer with Anchorage consulting firm Electric Power Systems (EPS). He’s been orchestrating energy infrastructure projects across the state for the better part of twenty years, and the Susitna dam has been on the drawing board the whole time.

Indeed, the 600 MW Susitna-Watana hydroelectric dam has been a dream since the ‘60s. If built, it would be the second-tallest dam in the United States. In the midst of federal pre-licensing studies in 2016, state funding for Susitna-Watana was vetoed, partly due to the oil price crash and partly for environmental reasons. Had the $5 billion project remained funded, proponents anticipated enough power to satisfy more than half of the Railbelt’s energy demand alone.

Which is unfortunate, he explains, because hydropower projects typically possess a 100-year project life, whereas other plants—like natural gas, for example—are closer to twenty or thirty years.

“So the hydro plant would pay for itself in the first thirty years, and then you’d have another seventy of making money,” he says, pointing to the Bradley Lake Hydroelectric Plant near Homer as a good example of a hydroelectric project that paid off its debt and now serves as an economic driver.

In many ways, the Susitna-Watana project can be seen as a microcosm of Alaska’s complicated relationship with renewable energy projects: financially, politically, and in technical execution.

The private investment matching requirements in government grants often prove to be a stumbling block, or in some cases an outright barrier. Pomeranz recalls a recent grant that his team were encouraged to apply for, but the private investment match totaling a cool $100 million proved too costly.

“The biggest thing for Alaska in terms of our available renewable energy sources is that we don’t have the infrastructure there to connect them,” says Pomeranz. He points to the Rural Electrification Act of the ‘30s as an example of what government measures could be taken to address this. “As part of Roosevelt’s New Deal, they pumped tons of money into making sure that everybody in the United States had power. I mean, they had distribution lines in the Lower 48 that ran miles just to a single guy in a farm.”

The Thayer Creek project reflects this reality all too well. A large portion of its funding will be allocated to the complex engineering and construction involved in accessing the creek situated seven miles from town and then transmitting electricity back to Angoon.

“That’s why this is a $34 million project,” Wunrow says. “If it was just putting in the hydro, it would probably be closer to a $6 million project. Getting to the water and getting the power back to the community—that is the expense.”

The fact that such a massive sum is being allocated to a town with a population smaller than your average American high school isn’t lost on Wunrow. However, he’s careful to note that Thayer Creek’s power production will far exceed Angoon’s current needs—by more than three times, according to DOE estimates—providing ample opportunity for future economic development and infrastructure upgrades.

US Department of Energy

When Thayer Creek wraps construction in 2028, it’s expected to supply 99 percent of Angoon’s energy needs, displacing an estimated 120,000 gallons of diesel annually and providing its 400 residents with clean power and stable rates for years to come. That’s one environmental benefit, common to most hydropower.

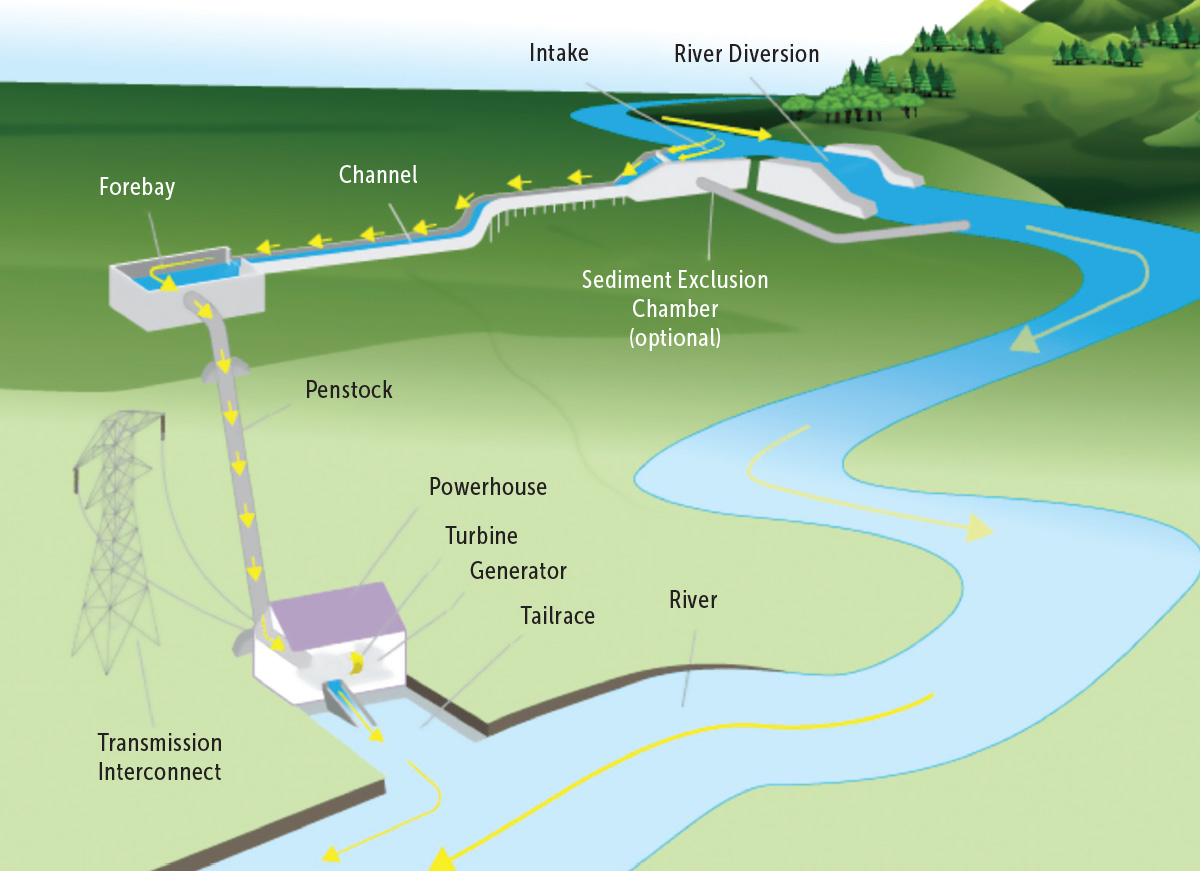

Better yet, unlike many other hydroelectric dams, Thayer Creek’s run-of-river design takes advantage of the creek’s natural elevation—often referred to as “head”—ensuring minimal impacts to Admiralty Island’s natural ecology. Instead of artificially elevating the creek level and harnessing power as gravity pulls the water downhill, the generator is placed at a bend in the river, where a shortcut channel taps part of the downstream flow.

“Run-of-river is a really, really great way to generate hydro because the water gets diverted but it still flows,” Wunrow says. “And there’s all kinds of things that are engineered in to make sure that it doesn’t have an adverse effect on fish or marine life.”

Wunrow says there were other creeks that may have been in contention, but none quite had that perfect combination of head, flow volume, and reflection of Kootznoowoo’s values as Thayer Creek. “It’s no coincidence that they [Angoon] decided on run-of-river. It’s part of a bigger stewardship mentality.”

Back when the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act (ANILCA) was being enacted, elders and community leaders from Angoon traveled to Washington, DC, to meet with congressional members and then-President Jimmy Carter.

“Leaders of Angoon went to DC and said, ‘We love the idea of preserving the land we’ve been using for 10,000 years—but we want a couple of things in return,’” says Wunrow.

One of those things, eventually included in ANILCA, was a single sentence that read: Kootznoowoo is granted the right to develop hydro power in the Admiralty Island National Monument.

“And that’s all it says,” Wunrow says with a laugh. “There’s nothing about exactly where, or what that means. But the truth is that the leaders of Angoon at the time had enough foresight back then to say one of the things we want is low-cost, sustainable energy.”

Fast forward a few decades, and it looks like Angoon’s leaders may finally have their wish.

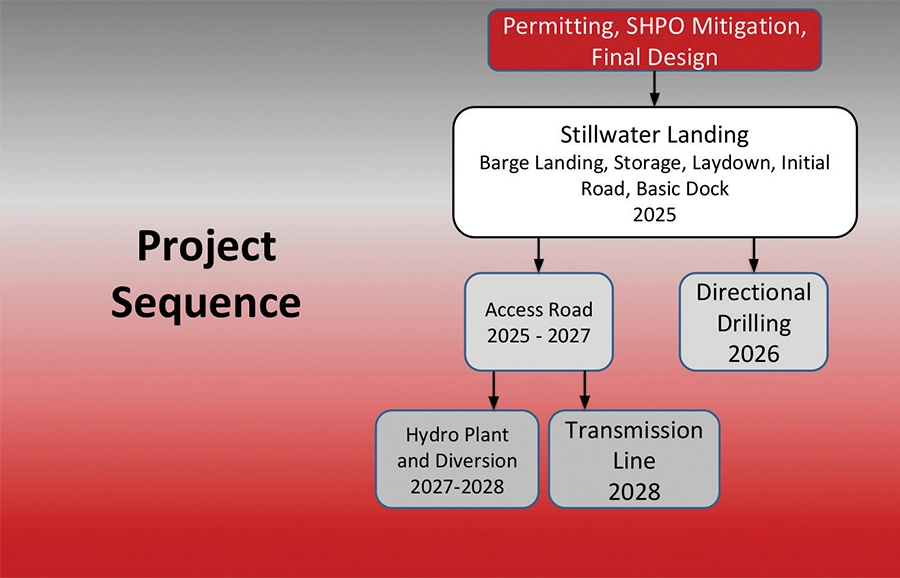

“This is a four-year project. There’s nothing that’s going to stop us from moving forward now,” says Wunrow, who is also the corporation’s tourism and natural resources director.

Wunrow stressed the, in some instances, unlikely partnerships that Kootznoowoo cultivated along the way.

“Historically, the Angoon Community Association have had a challenging relationship with the federal government in general, and the Forest Service specifically,” he explains. “The village is now surrounded by land that they no longer have any control over, and that’s been a challenge for the community to grapple with.”

In this case, though, less so. “I say this to everybody I have a chance to: the US Forest Service have been 100 percent behind Thayer [Creek], and they have literally moved mountains to help us through the permitting process,” says an energized Wunrow, revealing how the US Forest Service helped save the project millions of dollars in timber cutting fees and other costs.

That situation changed thanks to the 2021 infrastructure law. Wunrow says, “This OCED funding that we got, I think there’s a couple of sentences written into that legislation that specifically targets run-of-river, remote rural Alaska—and that has everything to do with Senator Murkowski’s office.”

The same announcement in March that Thayer Creek had been selected for DOE rural infrastructure money also spread some more around Alaska. Five projects split $125 million. The largest share, $54.8 million, goes to the Northwest Arctic region for solar, battery storage, and heat pumps, and $26.1 million goes to seven Interior villages for a similar setup.

Two other run-of-river hydroelectric projects received funding as well.

The Alutiiq Tribe of Old Harbor was allocated $10 million, and the Lake and Peninsula Borough was given $7.3 million for run-of-river hydro at Chignik Bay.

Meanwhile, last year a study by Dillingham-based utility Nushagak Cooperative completed initial field studies for run-of-river hydro on the Nuyakak River, a tributary of the Nushagak in the world’s largest red salmon watershed. Work on that project continued this year with a public survey, to be published in December.

Kootznoowoo

Introduced in 1984, Power Cost Equalization (PCE) plays a major role in making energy affordable for rural Alaska communities. Historically, this state-funded program has subsidized the high cost of electricity by covering the difference between local energy costs and the average cost in urban centers. This subsidy is vital for economic viability of remote communities.

However, integrating renewable projects such as Thayer Creek introduces a new dynamic. PCE subsidies are traditionally based on fuel usage, Pomeranz explains. Thus, as communities shift to renewable energy and reduce their reliance on diesel, the amount of PCE they receive would theoretically decrease.

Independent power producers (IPPs) are a workaround solution. By creating IPPs, communities can sell power back to utilities at a reduced cost, effectively leveraging the benefits of renewable energy without reducing their PCE subsidies. IPPs ensure that the economic advantages of PCE are preserved while communities transition to more sustainable energy practices.

Pomeranz stresses the importance of these partnerships, along with the creative measures Alaska’s energy leaders are taking to ensure its rural communities don’t get left behind.

“Right now, if you want funding for a project, you need a group or partnership with multiple entities,” he says. “And what the government is really looking at is putting together projects that are a consortium of community members—including tribes, nonprofits, and utilities—to come together to create a sustainable energy future.”

As with any landmark legislation—what US Representative Mary Peltola called a “once in a lifetime” opportunity for energy infrastructure—there’s always a learning curve. When asked about the time it took for the state to understand what was available and who was eligible, Pomeranz says, “I think we’re getting caught up, and a lot of people around the state are putting in a lot of hours to make sure that the state and its communities receive maximum funding.”

Pomeranz and EPS have not yet played a role in the Thayer Creek project, but that may change when the engineering and construction aspects go out for bid in 2025. And if Wunrow’s experience is anything to go by, it’s not the worst way to put in the extra hours.

“There are so many things I do with Kootznoowoo that are not as fun,” Wunrow says with a laugh. “But with this one, I know I can get on the phone—with the Forest Service or OCED or the mayor or whomever—[and] we’re all talking about the same thing and heading in the same direction. And that’s just rare.”