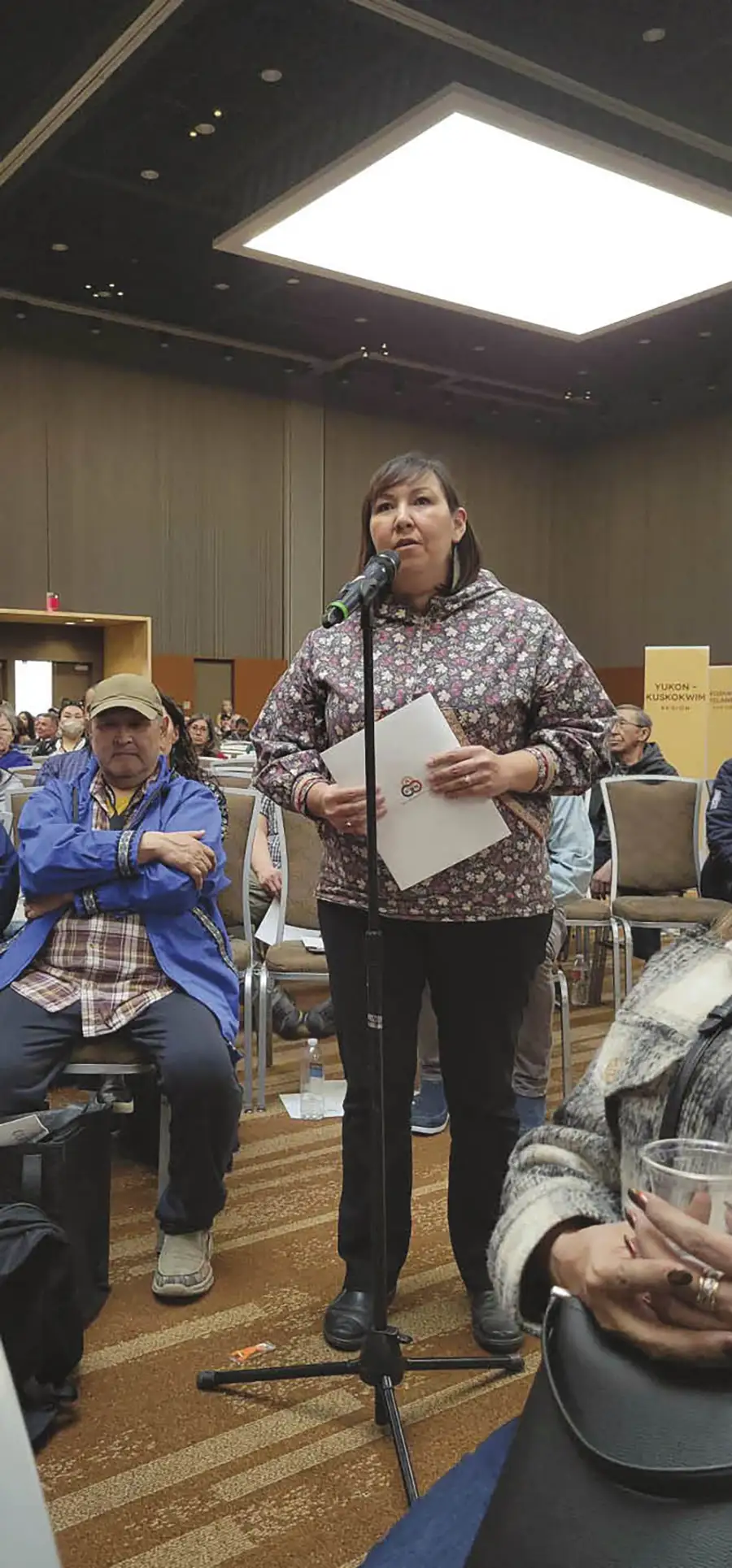

erena Fitka was born and raised in St. Mary’s, a small town on the Yukon River with a population of 600. Subsistence fishing is a way of life in St. Mary’s, and these last few years have been ghostly, according to Fitka, who is the executive director of the Yukon River Drainage Fisheries Association (YRDFA).

“It was eerie,” Fitka says. “Usually you see people passing by and you’re waving to them. And when you pass the fish camp, the smell of the smoke house going. You didn’t see the boats or the people at fish camp… It was a very empty, very deserted feeling on the river that first year.”

Almost all the king and chum salmon subsistence fisheries on the Yukon River were closed these past four years because of low returns. This year, there were small subsistence chum fisheries in the summer and fall, but only in a few places on the Yukon River. Between the closures, gear requirements, and the cost of gas, just a fraction of the population could fish, Holly Carroll says. Carroll is the Yukon River federal subsistence fisheries manager for the US Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS).

“I think it’s still a bright spot worth noting that the summer chum did get just better enough that we were able to meet that demand, that escapement goal, so we should celebrate that for sure,” Carroll says. “We just want to be careful [to] acknowledge that not many people got to make up for the food loss based on that.”

Researchers are looking for the cause of the population collapse and figuring out ways to address it. Community advocates are raising awareness and preserving their culture.

Five species of Pacific salmon live in the Yukon River, and all of them have decreased in population, but most research is focused on chum and kings, also known as Chinooks.

“When it’s that widespread across all spots on the Yukon—and it’s now affecting coho and it’s affecting kings and you’re seeing it across the North Pacific and in the Kuskokwim drainage as well—you’re like, ‘Wow, okay, something big is happening,’” Christy Gleason says. Gleason is the Yukon River fall season manager with Alaska Department of Fish and Game (ADF&G).

Scientists are looking at the sea for answers, Gleason says.

“The salmon that are coming to western Alaska are kind of experiencing death by a thousand cuts,” says Carroll.

The salmon are dealing with warming oceans, parasites, poor nutrition, and the destruction of their habitats, according to Carroll. And to make things more complicated, each species is affected in a different way.

There is a strong correlation between the king salmon population that arrives at Nunivak Island and the number of fish that make it back to the Yukon River, she says.

“That tells us that whatever is determining the run sizes for Yukon River Chinook salmon, it’s happening some time before we catch these fish in the survey,” Garcia says.

It’s the exact opposite situation for chum: the number of juveniles in the Bering Sea and the number of adults that return to the Yukon River show a weak correlation. This means that the problems they face are probably at sea, according to Garcia.

According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, there were record-breaking high temperatures in the Bering Sea in 2019. For Garcia, this suggests one theory: juvenile chum cannot build energy reserves as effectively in the warmth, which makes it hard for them to survive their first winter.

Yukon River Drainage Fisheries Association

Some fish have nowhere to travel. Some of the chum spawning grounds, or the places they return to deposit eggs, have dried up, Carroll says.

“If we had an answer, a smoking gun, I think we would all be really happy,” Garcia says. “But it’s not that simple.”

Another consideration is that king salmon populations have been declining for decades, down by 60 percent since 1984. While it remained relatively stable from 2000 to 2018, it was not rebounding, according to the US Environmental Protection Agency.

Now things are getting worse. This year saw the second-lowest number of king salmon return to the Yukon River on record, according to ADF&G. The lowest was in 2022.

“I’m still trying to teach them, but it’s hard when we’re cutting fish at our dinner table,” Fitka says. “It’s a little different than being outside… at the fish camp.”

Fitka is concerned that young kids won’t learn how to fish, and the young adults will lose interest. She says her nephews had the opportunity to fish this summer, but they decided to work instead.

Yukon River Drainage Fisheries Association

There are many important things that Yukon River communities get from salmon fishing. Food is high on that list, as are community and culture.

“We live by the seasons, we harvest by the seasons, so every season is an opportunity to harvest something, and once that season is over, we move onto the next,” Fitka says. “There’s a gap, there’s a missing piece, an empty feeling, a sense of loss.”

Bonnie Borba is a fall season research biologist for the Yukon Area Salmon Fishery, a management district under ADF&G. Area managers only have control of their regions. In this case, that means that they can make rules about what is done in the Yukon River, but not outside of it. Salmon, being anadromous fish that leave the river to spend much of their lives in saltwater, are therefore difficult to manage. Borba can only do so much within her jurisdiction.

“The only tools we have for our fishing stuff is time and area. So in this case, it’s no time in any area,” she says.

When fish populations are as low as they have been, sometimes the only thing that can be done is monitor populations and close fisheries, Borba says.

Yukon River Drainage Fisheries Association

One human cause that Yukon River communities are looking at is commercial fishing in the Alaska Peninsula and Aleutian Islands Management Area, or Area M. Many people argue that limiting the pollock harvest in this area will allow more salmon to return to spawning grounds and support subsistence fishing. In February, the Alaska Board of Fisheries received a proposal from ADF&G to amend the Area M management plan. The board rejected the proposal but adopted a more limited restriction instead.

It’s not clear if the Area M amendment is why there were stronger salmon returns to the Yukon River this summer.

“Since this is the first year this happened, those restrictions, that’s not enough data to go on to make any kind of correlation of whether or not it produced more fish for us,” Borba says. “There was already indication the year before that the [group of fish] was going to be better this coming year.”

While Yukon chums cross the Aleutian Islands into the Gulf of Alaska, a lot of the fish that pass through Area M are local to western Alaska, according to Carroll, adding that the best thing that FWS can do to address the low salmon population in the Yukon is understand why it is occurring and alleviate the impacts of the canceled subsistence harvests.

“It’s not the rosy picture; it is still not what the traditional needs are,” Carroll says. “It’s a bright spot if you want to look at it that way—if you’re a glass half full kind of person—but if you’re trying to feed a family, it’s not going to feel that way.”

The YRDFA has assisted multiple surveying efforts, according to its fall newsletter. But there are other important things to do, like raise awareness of the situation.

While kings and Yukon chum and coho are declining, other fisheries are thriving. This past season, more than 50 million sockeye salmon were caught in Bristol Bay, ADF&G reported. And there have been several record-breaking seasons in recent years for the fishery.

“All I hear is Bristol Bay’s is booming, the fisheries are good, but there’s half the state where our fisheries are not doing good and half the state where people are not getting fish,” Fitka says. “Our voices need to be heard too.”

In August, YRDFA had a booth at Wild Salmon Day in Anchorage—part of a statewide celebration enacted in 2016—and spoke to people about the struggles with salmon in the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta region.

“It was surprising how many people didn’t know about the hardships that the Yukon River communities are facing,” its newsletter states.

YRDFA isn’t the only organization working to save the salmon in the Yukon River. Tanana Chiefs Conference revived its Yukon River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission this year, and Congress established the Alaska Salmon Research Task Force (AKSRTF). The task force published a draft Alaska Salmon Research Task Force Report in October. The AKSRTF bimonthly meetings are open to the public, and it will be taking comments for research recommendations and feedback until March 15.

Fitka says, “The more people that are aware of the conditions and the collapse of our salmon, the more allies we can have, more voices we can have to advocate for our rights and mostly for the rights of the salmon.”