elcome to the northernmost town in the United States, Utqiaġvik. The name, meaning “place where tubers are gathered” in Iñupiaq, was adopted in 2016 by voter referendum. The settlement has also historically been called Ukpeaġvik, meaning “place where snowy owls are hunted.” The old name Barrow comes from the continent’s northern tip, Point Barrow, named in 1825 for English geographer John Barrow.

“Barrow” is still commonly used by locals; if nothing else, it refers to the town’s central neighborhood. Three lagoons divide Barrow from Browerville, a mostly residential area extending to Cakeeater Road, which loops around the town’s wild backyard. Contact Ukpeaġvik Iñupiat Corporation (same building as the Stuaqpak Quickstop) for a permit to set foot on the tundra, and always be wary of polar bears.

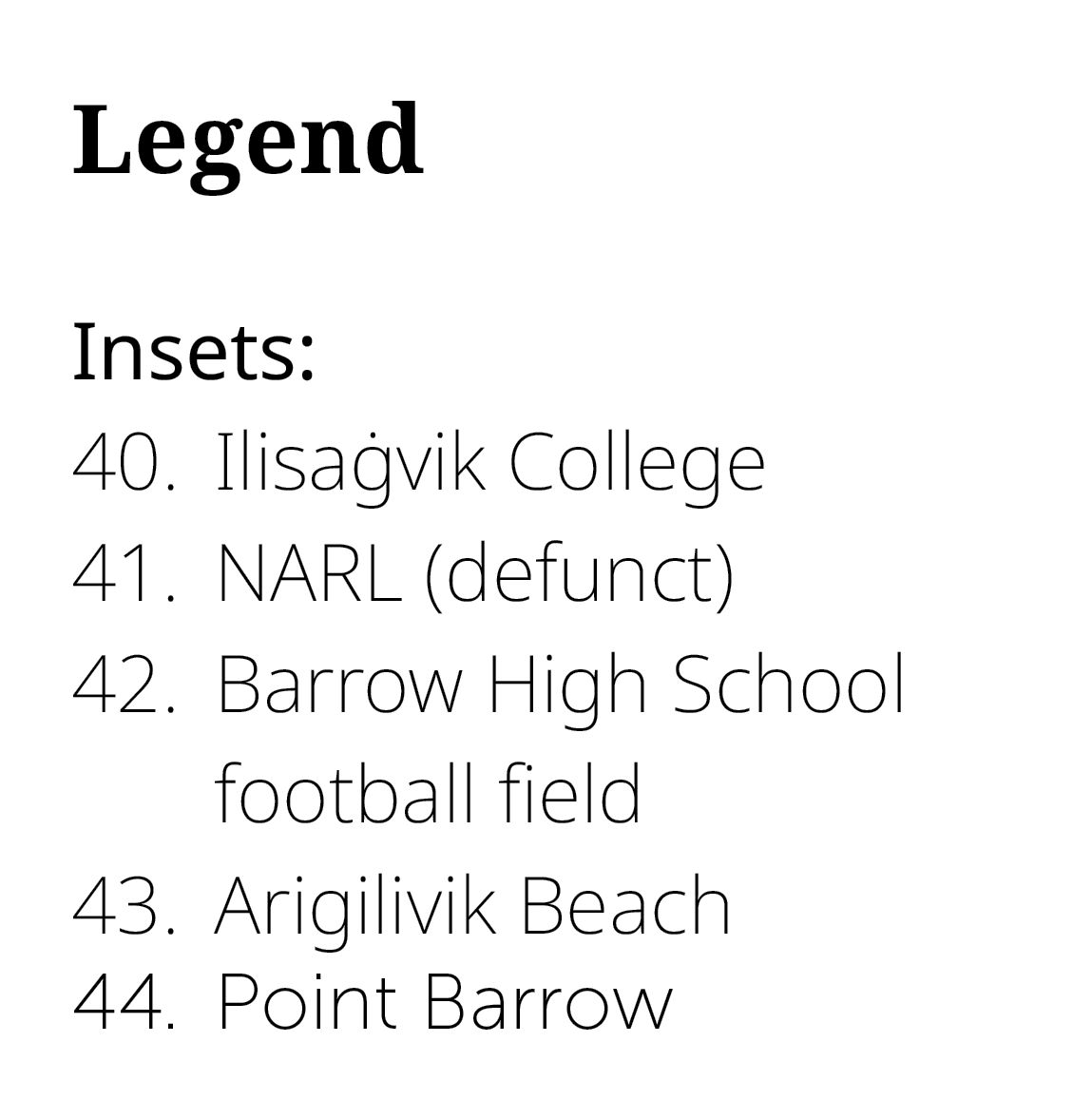

North of town, on the road to Point Barrow, the former Naval Arctic Research Laboratory forms the outlying neighborhood of NARL, home of Iḷisaġvik College (until its new campus in Browerville is built). The cluster of rusting Quonset huts is worth a look, but it is outside of walking distance.

Getting around on foot in Barrow and Browerville is easy enough, right from the airport, but pedestrians should watch out for ATVs, side-by-sides, and (yes) cars and trucks on the unpaved streets. This map shows useful and interesting places in Utqiaġvik, from the Funakoshi Memorial marking ancient sod mounds on the coastal bluff to the Steamdot coffee shop inside the Stuaqpak supermarket. Feel free to remove or photocopy these fold-out pages.

During your visit, remember to dress for the weather. Mid-June is spring breakup; daytime temperatures can still drop below freezing. That fact should add to the respect for year-round residents who make their homes in the most extreme city in America.

This ancient way of life aligned with the commercial interests of Charles Dewitt Brower, a New Yorker who settled in the Arctic in 1883.

That extinct industry left its mark in several ways, as did Brower himself. His grandson, Harry Brower Jr., is now the mayor of the North Slope Borough and a whaling captain. His was one of the thirteen crews that celebrated their successful 2023 spring harvest at Utqiaġvik’s Nalukataq festival in June.

The rescue base that Charles Brower built for shipwrecked sailors served as the town’s first Presbyterian missionary school. The blend of Christian religion and Indigenous spirituality manifests when celebrants join hands in prayer and thank God for providing whales.

“Happy Nalukataq,” people say as they gather inside a windbreak built with scaffolding and tarps. Crawford Patkotak, vice chairman of the Alaska Eskimo Whaling Commission, serves as master of ceremonies and makes sure everyone gets a helping of soup and bread dished out by the host crews.

The main event is the blanket toss; “Nalukataq” means “to toss up” in Iñupiaq. Crews rig a sealskin blanket at shoulder height. Few jumpers can land on their feet more than three times in a row. While in the air, they scatter bags of candy like human piñatas.

The catch is distributed among the community, and the tongue, heart, and kidneys are kept separate from other meat. Cellars dug into the permafrost preserve tons of meat and blubber during the weeks between the successful hunt and the festival. By the time Nalukataq is held, all parts of the whale have been given away. The inedible joint at the root of the tail remains on the ground.

With their names, logos, colors, and uniforms, whaling crews are like sports heroes in Arctic communities, and their harvests are hailed like victories. Utqiaġvik has anywhere from twenty-five to forty-five crews registered in any given year.

The International Whaling Commission has allotted up to 392 bowhead whales to be taken from 2019 to 2025 in the Bering, Chukchi, and Beaufort Seas. For 2023, the quota for the Alaska Eskimo Whaling Commission is 93 strikes, carrying forward unused strikes from previous years.

Whalers have more work to do before the fall hunt. Crews are busy harvesting caribou and freshwater fish from inland. Walrus and bearded seal add to the cache of winter foods, and the seal skin goes toward a new blanket.