ater lit the muddy streets of Juneau City, as the gold mining town was known in 1893. That was the year Alaska Electric Light & Power (AEL&P) started providing service from a simple water wheel. Two decades later, the utility developed the Annex Creek, Salmon Creek, and Gold Creek hydropower plants, and they remain in service, generating 3.6 MW, 6.7 MW, and 1.6 MW, respectively.

Juneau is awash in hydropower, especially since the federal government build the Snettisham project in 1973. Water tapped from two lakes 28 miles southeast of Juneau drives 70 percent of Juneau’s electricity, with a peak output of 78 MW. Another 20 percent comes from the Lake Dorothy facility on the east bank of Taku Inlet, generating up to 14 MW from the flow of water down a 5-foot diameter penstock. And that’s just Phase 1; AEL&P has plans to double the output from Lake Dorothy, as demand warrants.

“Under the right circumstances, hydropower is a cost-effective and reliable source of carbon-free electricity,” says Debbie Driscoll, AEL&P vice president and director of consumer affairs.

AEL&P isn’t 100 percent carbon free; Driscoll notes that the utility burns diesel for standby generators during planned maintenance and short outages. However, AEL&P is unique in Alaska having such a large portion of its generation portfolio come from hydropower. Most Alaska utilities rely on a combination of natural gas, petroleum, and coal, plus a smattering of renewables in addition to hydropower. Juneau stands as a benchmark for others to measure up to.

The Bradley Lake Hydroelectric Project took forty years of planning, fieldwork, licensing, construction, and agreements before generating any power. The US Army Corps of Engineers first studied Bradley Lake’s potential in 1955, but it wasn’t until 1962 that Congress authorized the project. Another twenty years passed before the Alaska Energy Authority (AEA) assumed responsibility for the project and completed the final steps, including the Power Sales Agreement between AEA and the Railbelt utilities and acquiring a mix of legislative appropriations and AEA revenue bonds. In 2020, AEA completed an expansion by diverting glacial water from West Fork Upper Battle Creek into Bradley Lake Hydroelectric Project, increasing energy by 10 percent from its initial numbers in 1991.

Now AEA, in partnership with the Railbelt utilities, is pursuing another diversion project to further increase the power output at Bradley Lake by almost 50 percent. The Dixon Diversion would divert water from the East Fork of the Martin River into the Bradley Lake reservoir. According to a press release from Governor Mike Dunleavy, the Dixon Diversion Project could power an additional equivalent of up to 30,000 homes. At this time, AEA estimates five years of studies and permitting followed by five years of construction before the Dixon Diversion generates power.

ORPC

ORPC

“Even though the plant is paid off, there is still a commitment by the Railbelt utilities to continue debt payments until 2050,” Thayer explains. “There is a stipulation in the Power Sales Agreement that AEA doesn’t need legislative approval to appropriate these funds as long as it goes to the betterment of Bradley Lake and participating utilities.”

This provision means costs for upgrades won’t flow down to utility ratepayers or place an additional burden on the state treasury. Upgrading transmission lines from Fairbanks to Homer is estimated to cost around $200 million.

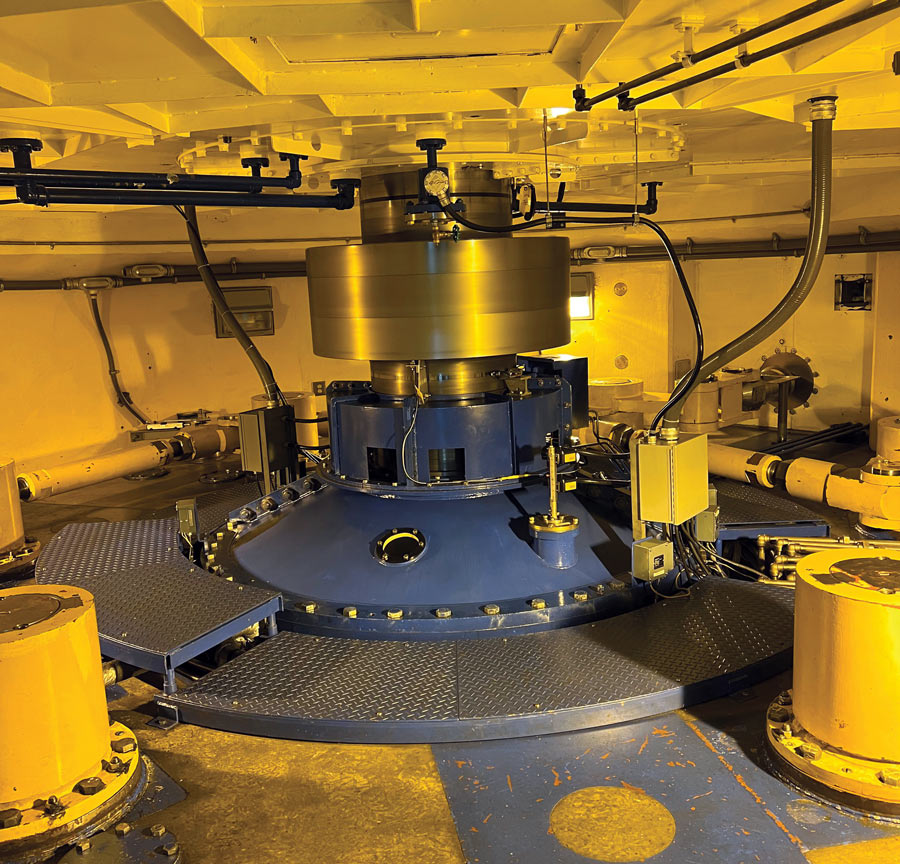

For Igiugig, that solution came from a partnership with Ocean Renewable Power Company (ORPC), a global renewable energy company with offices in Anchorage. The village, situated where the Kvichak River enters Lake Iliamna, had for a long time imported expensive diesel fuel for power generation. In 2014 when ORPC installed its first hydrokinetic project, known as the RivGen Power System, Igiugig saw the possibility of expanding its energy options. As ORPC further developed the technology, advanced versions of the power system proved capable of providing one-third of the electricity needs for the village’s seventy Yup’ik Eskimos, Aleuts, and Athabascans.

ORPC’s Alaska Director of Development Merrick Jackinsky says that the RivGen Power System is unique because it doesn’t require large-scale construction or permanent infrastructure to produce electricity. RivGen differs from traditional hydropower plants, which rely on the elevation difference between the intake and outlet. Hydrokinetic devices like RivGen are placed directly in a stream of flowing water, extracting energy with turbines. The RivGen system looks like a small watercraft with its generator, consisting of two turbines, connected through a single driveline to an underwater generator in the center. The generator sits on a pontoon that is self-deploying, easy to install, and easy to retrieve for maintenance or seasonal removal.

Each device has a rated capacity of 25 kW. ORPC ships components to a staging area near a project site for final assembly. Once assembled, the RivGen device is towed to the project site and anchored there. The device is held in the river or tidal current by the anchor lines and then ballasted into position on the riverbed. An underwater power and data cable runs along the river bottom to an onshore interconnection point.

“It’s a low vertical profile system,” says Jackinsky. “There aren’t any dams or reservoirs creating free-flowing water. It’s a small system with flexible applications.”

AEA

AEA

ORPC also announced a tidal generation project in Port Mackenzie that will produce the 80 kW of power needed for a cathodic protection system that keeps the dock from corroding into Cook Inlet. Unlike the freshwater project in Igiugig, the system will require further adaptation for operation in salt water. If successful, it will be the first saltwater tidal generation system in Alaska.

AEA

AEA

Though ORPC systems have a low vertical profile and removable infrastructure, Jackinsky says the company is still required to conduct environmental impact studies in areas where wildlife is prevalent. The most extensive monitoring areas are where endangered beluga whales live and in locations with salmon runs. To date, no significant impacts have been found.

Hydrokinetic technology opens new possibilities for Alaska to harness its liquid energy, from free-flowing rivers to the wine-dark sea. They have the advantage of being deployable in more locations than the very particular topography that traditional hydropower requires. According to AEA, there are fifty operating utility-scale hydroelectric projects in Alaska, supplying 27 percent of Alaska’s energy profile. Thayer notes that Alaska’s fraction of electricity from hydro is 25 percent more than the national rate. The vastness of Alaska’s coastal miles and waterways gives the state a significant renewable energy advantage over the Lower 48, says Thayer, and communities will benefit from continued investments in hydropower and related infrastructure.

![]()